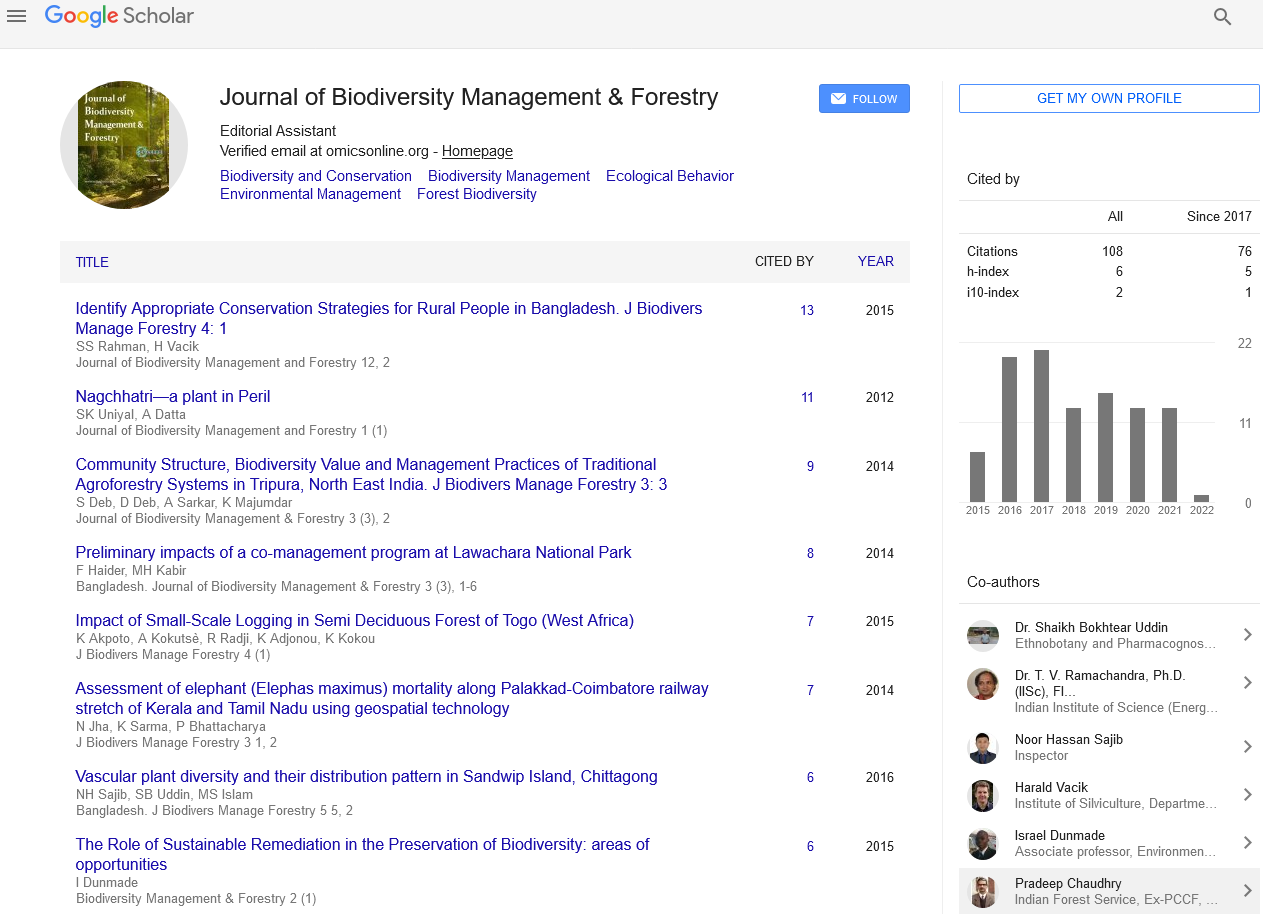

Letter to Editor, J Biodivers Manage Forestry Vol: 6 Issue: 1

Why Flightless Birds are Condemned to Lay Eggs

| João P Barreiros* | |

| CE3C – Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes / Azorean Biodiversity Group and Universidade dos Açores - Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias e do Ambiente, 9700-042 Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal | |

| Corresponding author : João P Barreiros CE3C – Centre for Ecology, Evolution and Environmental Changes / Azorean Biodiversity Group and Universidade dos Açores - Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias e do Ambiente, 9700-042 Angra do Heroísmo, Portugal Tel: (+351)295402200 E-mail: joao.ps.barreiros@uac.pt |

|

| Received: January 27, 2017 Accepted: February 02, 2017 Published: February 09, 2017 | |

| Citation:Barreiros JP (2017) Why Flightless Birds are ‘Condemned’ to Lay Eggs. J Biodivers Manage Forestry 6:1. doi: 10.4172/2327-4417.1000172 |

Abstract

Birds evolved very fast and are the only vertebrate group that never turned to ovoviviparity. While this is explainable as an evolutionary pressure for feathered flight and reduced size, their fast evolution apparently caused the disappearance of a significant proportion of genes. However posterior evolutionary trends of Aves to become flightless and with increased body sizes were not accompanied by an ‘expected’ turn to ovoviviparity, something known for a number of reptile taxa (e.g. some constrictor serpents). This impossibility is particularly noted in marine flightless birds from which penguins are certainly the best extant example having to endure seasonal extreme energy losses when coming ashore to lay eggs. This same limitation was most certainly the major cause for the extinction of the largest marine bird in the Northern Hemisphere – The Great Auk Pinguinus impennis. Here we discuss why ovoviviparism is probably an impossibility for birds while proposing lines of research that could prove, or disprove, our hypothetical and speculative view.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi