Review Article, J Tourism Res Hospitality Vol: 11 Issue: 9

THE ROLES OFINDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE AND HERITAGE RESOURCES FOR CULTURAL TOURISM DEVELOPMENT IN KONSO WORLD HERITAGE SITE, SOUTHWESTERN ETHIOPIA

Solomon Eshete Woldekiros*

Department of Geography and Environmental Studies, Dilla University, Dilla, Ethiopia

*Corresponding Author: Solomon Eshete Woldekiros

Department of

Geography and Environmental Studies,

Dilla University,

Dilla,

Ethiopia,

Tel: +251-0926134893;

E-mail: solwoldekiros2017@gmail.com

Received date: 20 June, 2022, Manuscript No. JTRH-22-67111; Editor assigned date: 23 June, 2022, PreQC No. JTRH-22-67111 (PQ); Reviewed date: 07 July, 2022, QC No. JTRH-22-67111; Revised date: 19 August, 2022, Manuscript No. JTRH-22-67111 (R); Published date: 26 August, 2022, DOI: 10.4172/2324-8807.10001002.

Citation: Woldekiros SE (2022) The Roles of Indigenous Knowledgeand Heritage Resources for Cultural Tourism Development in the Konso World Heritage Site, Southwestern Ethiopia. J Tourism Res Hospitality 11:9.

Abstract

Cultural heritage resource based tourism has become one of the largest and fastest growing segments of the tourism industry. It is also one of the possible development tools for local communities in developing countries. Indigenous knowledge practices and value systems in traditional rural societies have become the main forces for the production of cultural heritage resources. The cultural heritage resources can be categorized as tangible and intangible heritages and characteristically consist of movable and immovable assets inherited from the past.

Keywords: Cultural heritage, Inherited, Communities, Segments, Tourism

Introduction

Cultural heritage resource based tourism has become one of the largest and fastest growing segments of the tourism industry. It is also one of the possible development tools for local communities in developing countries [1,2].

In this regard, Africa has historically made a multitude of contributions to world civilization. A few of African heritage resources recognized by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) include the great Zimbabwean wall constructed by the Shona community, the wall of Benin City, the Sungbo's Monument, built by the Yoruba people, the great Mosque of Djenne in Mali and the Nubian and Egyptian great pyramids which are the heritage resources built during the pre colonial period [3]. Sites such as kasubi tombs in Uganda, Timbuktu in Mali, and the barotse cultural landscape in Zambia are also traditionally conserved by local communities and remained as cultural tourism destinations.

Likewise, Karbo acknowledges that Ethiopia is one of the oldest countries with diverse cultural elements in the world [4]. The architectural designs and handcrafts such as the monolithic steles in Axum and Yeha; the Rock hewn churches of Lalibella and many under cave churches, rock paints and drawings; the Brana Ge'ez scripts; built up walls of the city of Harar (Jugol); the tiya and gedeo carved standing stones; the dawro fortified wall (halalla) and the Konso walled cultural villages are the major cultural heritages that are all the works of local crafts produced by the indigenous knowledge systems and practices in Ethiopia. These days, these and other prominent cultural heritage sites in the country have been attracting immense international and domestic tourists. Various sources also revealed that Ethiopia is among a few countries in the world that have an alphabet and calendar which is the result of keeping and rehabilitating indigenous knowledge systems [5,6].

With diverse tourist attractions, Ethiopia has great comparative advantages being located in the strategic position near to most tourist generating regions of Europe and Asia. The country is closer to the birthplaces of the dominant religions such as Christianity and Islam, in the Middle East. The traditional education provided in religious institutions has played a great role in the country. Communities in various parts of Ethiopia have also various indigenous knowledge practices that enabled them in the production of different resources used to improve their livelihood basis. These include hardening metal in traditional blacksmith, producing and selling furniture made of Bamboo and Sisal in Awassa and Addis Ababa, horn works in Wolqite, Wolisso and Tilili areas, hillside terracing and dry stone building are also common in Konso and Dawuro areas. The Gamo community conflict management system and the Gedeo community agro forestry practices are also indications of the role of the indigenous knowledge for maintaining peace and conservation of the environment respectively. Therefore, this paper investigates the cultural heritage resources that produced by the indigenous knowledge, value systems and rituals of the Konso community that has paved the ways for cultural tourism development in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site in Southwestern Ethiopia.

Aims and objectives

This paper emphasized on the investigation of the indigenous knowledge practices and values of the Konso community that contribute to the development of cultural heritage tourism in Konso area. It is aimed at exploring the major cultural heritage resources produced by the indigenous knowledge that paved the ways for cultural tourism development. Moreover, the paper examines the social and economic benefits; factors affecting the involvement of the local community in to tourism and the pitfalls hindering the development of cultural tourism in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site in South western Ethiopia.

Literature Review

Indigenous knowledge practices and value systems in traditional rural societies have become the main forces for the production of cultural heritage resources. The cultural heritage resources can be categorized as tangible and intangible heritages and characteristically consist of movable and immovable assets inherited from the past. Although the term indigenous knowledge has miscellaneous interpretations and meanings, some scholars defined Indigenous knowledge (IK) as a cumulative body of practices, techniques, tools, intellectual resources, beliefs, values and strategies that accumulated over time in a particular locality [7]. Indigenous knowledge practice is inherited in successive generations basically through oral traditions without the interventions and impositions of external forces [8].

In this regard, historically, the ancient African civilizations have brought sophisticated knowledge systems deeply rooted in local cultures, social and administrative systems. Mehta, Alter, Semali and Maretzki also suggest that the indigenous knowledge as local knowledge aggregated by communities over generations, reflecting many years of experimentation and innovation in almost all aspects of human life [9].

However, largely in Western oriented academic discourse and investigations; the African perspective has either been marginalised or repressed because indigenous knowledge and methods have been disregarded [10]. Scholars also suggest that the Eurocentric philosophy of education and ideologies paved the way for the dominance of epistemic communities and their institutions seriously affected many of the African indigenous knowledge systems. In this regard, Mutekwe asserts that the subsequent processes of colonization, cultural imperialism, and modern forms of schooling also tend to degrade many of the indigenous knowledge systems, values, and practices of Africans.

Many African scholars argue that it could be difficult to classify the eurocentric and afrocentric philosophical dichotomy. The sources of the Eurocentric philosophy that could be developed by ancient scholars such as Plato and Aristotle were from the African philosophy. ‘It would not do well for philosophy to be Eurocentric or Afrocentric, it should rather roll over all continents to remain anthropocentric’. Owusu-Ansah and Mji thus, they believe that the afrocentric academic orientation would be interrelated with the Eurocentric ones.

On the other hand, many of the African treasuries and properties which were the results of the African indigenous knowledge were looted and taken to the home country of major colonial powers. For instance, during the colonial era, the Europeans looted over three hundred fifty treasures in 1868 from Ethiopia, a country which has never been colonized. Even, in the post colonial era, the colonial powers had imported western driven methods of conservation by ignoring African local philosophies and traditions as unscientific and retarded. From the above given premises one could argue that if the western world undermines and disrespects the African Indigenous knowledge and values, why should they have plundered many of the heritage resources produced by the indigenous Knowledge from Africa?

Empirically, there is an increasing aspiration among governments to get recognition to protect their tangible and intangible heritage sites to obtain stable foreign earnings from the tourism industry. Governments and international organizations that advocate neoliberal principles have encouraged the role of the private sector in tourism development. Some of these financial institutions include the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank (ADB).

Likewise, the tourism industry in Ethiopia emerged as a new economic earning in the early 1960’s. Tourism recognized as a sector for economic growth and development grew at an average annual rate of 12 percent until 1974. From 1970-1973, the average number of international tourist arrivals in Ethiopia was 63,833 per year; whereas, the average annual revenue received was USD 10.2 million with an average annual growth rate of 13 to 18 percent [11]. After the dergue assumed power in 1974, because of the ideological differences and weak diplomatic ties with the western world, the arrival of tourists and the revenue generated was drastically declined. This was because North American and Western European countries were the main international tourist generating regions. For instance, tourist arrivals and revenue collected from tourists were seriously declined from 50,220 in 1975 to 30,000 in 1977 and from 22.2 million Birr in 1974 to 3.3 million Birr in 1978, respectively.

Tourism growth and development in Ethiopia has been characterized by a fluctuating trend in terms of the number of international tourist arrivals and revenue generation from regime to regime. For instance, the number of tourist arrivals in Ethiopia reached 468,000 in 2010, 523 in 2011 and increased to 596,000 in 2012. The corresponding revenue generated was USD 522 million, USD 770 million and USD 607 million in the years indicated respectively. However, the revenue generation of the country had further reduced to USD 416,000 in the year 2013 [12]. The total contribution of travel and tourism to GDP in Ethiopia was ETB 78,676.4 mn (USD 3, 620. 6 mn), 5.7 percent of GDP in 2016 and it was ETB 121,435.0 mn (USD 5, 074.3 mn), 6.8 percent of GDP in 2017.

Some of the pertinent theories and models widely used in the study of tourism and indigenous knowledge creation and dissemination that were proposed by scholars have been assessed and examined to guide this study. These include doxey irridex's (1975) four staged tourism model, the richard butler's (1980) six-staged Tourism Area Life Cycle (TALC) model, the Social Exchange Theory (SET), the theory of stakeholders, roger’s Theory of Innovation Diffusion Model (TIDM), and Cohen's Theory (1972) of host-guest behavior. Besides, the Tacit and Explicit Knowledge creation and transfer, how the indigenous knowledge transferred through intergenerational ways, and the Tobler's first law of geography, to see the relative involvement of near and distant local community members into the tourism development, have also been considered. Because of the complex nature of the study of cultural heritage tourism in particular and the tourism industry in general, a single theory or model might not necessarily satisfy to guide as a lens and make better analysis in this study.

Framework of the study

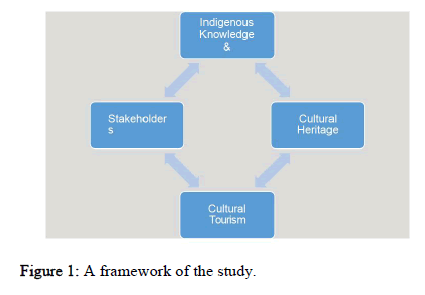

The framework was adopted by the author of this paper and contains four stages which have been interconnected by arrows directly. The arrows show the interrelationships among the components in which the existence of one component or element depends on the other components in the system. This framework of the study is shown in Figure 1.

The framework illustrated in Figure 1 consists of four components shown in the rectangles which are interconnected to one another by thick arrows and are explained as follows.

Indigenous knowledge practices: The interactions between the Konso community and its environment have become a prerequisite for the creation of indigenous knowledge practices, value systems, and rituals. The community has continuously interacted with the immediate surroundings to satisfy its basic needs. The interaction between the Konso community with its physical, biological, and cultural environment as a survival mechanism and ways of knowledge production and transfer could take the form of tacit and explicit knowledge. The ideas, practices, and rituals are disseminated through the process of innovation diffusion theory.

The Konso community lives in a tropical hardship environment experiencing poor and fragile soils, rugged mountain and stony topography, deficient surface and groundwater resources with low rainfall distribution, and vulnerability to food shortages and food insecurity. However, the Konso community is known for the IK practices of agricultural bench terraces, the building of dry stone walls, and ponds as their way of life.

Cultural heritage resources: Among the many outcomes of the indigenous knowledge practices, values, and rituals of the Konso community, this study was only confined to the cultural heritage resources as the main inputs for the development of cultural tourism in attracting tourists. The agricultural terraced fields and ponds, the anthropomorphic wooden sculptures, the dry stone walled villages, the ritual ceremonies and mummification of the body of ritual leaders are among others.

Cultural tourism development: The tourism industry does not occur randomly everywhere; however, it happens only when certain natural and human conditions are fulfilled. The same happens for cultural tourism in which cultural heritage resources such as material objects, artifacts, archeological sites, monuments, landscapes, and similar other cultural entities exist. In this context, if the Konso indigenous knowledge practices had not produced the various cultural heritage resources, there would have not been cultural tourism development in the area today.

Stakeholder involvement and conflict of interests: There are many stakeholders involved in the conservation of heritage resources and the cultural tourism industry. However, this study exclusively focused on the main stakeholders such as the local community members, the government tourism agencies at different levels, the local private investors involved in the tourism activities, and the tourists visiting the destination during data collections. If there is conflict of interests among stakeholders due to misunderstanding and the unmanaged conflict of interests might lead to deterioration of heritage resources that harm the tourism industry. Constitutes one of the most vital resources for tourism development.

Materials and Methods

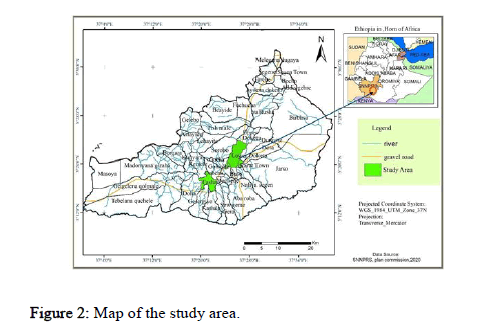

This study was conducted in the Konso tourist attraction area. The Konso Woreda (now a zone) is nearly located between 5°15′ 45″ to 5°36′ 15″ North latitude and from 37°4' 00″ to 38°17′ 30″ East longitude (Figure 2). In terms of relative location, the Konso area is bounded in the north with the Dirashe Woreda, in the south and southwest of south Omo zone, in the south and southeast with the Borena zone, and in the east and northeast with Burji woreda. The Konso Woreda is about 592 kilometres away from Addis Ababa, the capital city of the country, and 320 kilometres from the regional state capital, Hawassa in the southwestern directions, respectively. It is also about 80 kilometres away south of Arba Minch town. The map of the study area is shown in Figure 2.

The Konso Woreda is inhabited by the Konso community and the area is part of the southern Ethiopian Rift Valley system. The total area-size of the Konso Woreda is about 23,000 hectares or 2,569 square kilometers. Out of this total area of the Konso Woreda, the cultural landscape world heritage site covers about 55 square kilometers, in which the submission process started in 1997 to WHC/ UNESCO and lastly recognized in 2011 as a universal value of humanity.

According to the 1994 national population and housing census result, the total population of the Konso Woreda was 157,585, where 77,147 males and 80,438 females, which consisted of 29,629 households. According to the census result, 5,479 or 3.48 percent of its population was urban dwellers.

Based upon the 2007 national population and housing census, Ethiopian Central Statistical Agency (CSA, 2008), reported that the Konso Woreda now Zone had a total population of 235,087, of which 113,412 were men and the remaining 121,675 was women. On the other hand, the Konso population, at the end of 2018 was projected to be 299,622. Out of this population, 144,421 men and the remaining 155,211 were women. The population of the Konso was characteristically unique in that the number of women outweighed that of the men population by nearly about 8,000 in the 2007 national census and 10,790 in the 2018 projection.

Philosophical foundation and paradigm

There are two dominant ontological and epistemological traditions in a research world, namely positivism and interpretivist paradigms. Interpretivist positions are founded on the theoretical belief that reality is socially constructed and flexible. In an interpretive qualitative methodology, reality is socially constructed as researchers interact with participants by seeking their perception or experience on a particular problem.

Data types and sources

This study focused on a qualitative research approach in which both the primary and secondary data sources were identified and collected from various sources. The main primary data sources were generated from the local community, who involved in the conservation and transfer of IK, values and values; the culture and tourism government agencies, and experts, the private sector, especially the investors engaged in tourism and tourism-related businesses, and those tourists visiting the sites during data gathering periods. The data were collected through in-depth interviews, focus group discussion, and field observation in collaboration with the data collectors or interview and focus group discussion moderator. Secondary, data were also collected and assessed from different sources such as annual reports, archived records, journal articles, books, and other documents.

Data gathering instruments

Face to face interviews as the primary data gathering tool was employed to generate information through semi-structured open ended questions from the local elders, the culture and tourism experts working in Konso Woreda/Zone Culture and Tourism Office (KWCTO), South Region Culture and Tourism Bureau (SRCTB) and Ethiopian Ministry of Culture and Tourism (EMoCT). Moreover, the private investors who owned the lodges and hotels involved in various tourism businesses in the Konso area and the tourists visiting the selected sites during the data collection period were also interviewed.

Focus Group Discussion (FGD) was also used to generate data from the local community members who have been involved in cultural heritage tourism activities. FGDs were carried out by moderators. Four focus groups were organized from Karat town, Gamolle, Fasha and lower Dokatu villages comprising six participants each. And field observation was also made by the author. The author took notes, and captured relevant photographs used in the analysis. Although several stakeholders have been involved in the tourism industry, this study only focused on the main stakeholders such as the local community members, the culture and tourism government institutions from local to federal levels, the private sector, and the tourists visiting the site during data collections. This means, the study did not include the other stakeholders involved in the tourism industry such as the media, the academics, tour operators and travel agents, transporters, and financial institutions to reduce the complexity of data collection and the number of research participants manageable in the qualitative research study. The research participants were the potential stakeholders who have strong attachments to the indigenous knowledge, heritage resources, and cultural heritage tourism in the study area.

Sampling techniques and sample size

Sampling techniques: In interpretive paradigm, ethnographic research design, and a qualitative approach, non-probability sampling procedures, predominately purposive and snowball sampling techniques are desirable. Etikan and Bala suggest that among the nonprobability sampling techniques used in qualitative studies, purposive and snowball sampling techniques were commonly employed. Therefore, the author employed the purposive, accidental and snowball sampling techniques to select the required participants of the study.

Sample size: Because of the large area size of Ethiopia and the presence of enormous world heritage tourist sites and the financial resource constraints, among the four world heritage sites in the Southern Ethiopia such as of the Lower Omo Valley, the Tiya Carved Standing Stone, and the Fiche Chamballala (the Sidama people's New Year), this study was delimited to the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site in the Southwestern parts of Ethiopia. The Konso cultural landscape world heritage site was purposefully selected for this study because it is a unique living cultural tradition that is highly tied to indigenous knowledge practices, value systems, and rituals that resulted in the production of the cultural heritage resources.

In general, there were thirty nine villages in the Konso administrative area. However, only twelve cultural villages, which distributed over fifty five square kilometer area were incorporated into the Konso cultural landscape, which UNESCO inscribed the site as a world heritage site in 2011 (SRCTB, 2016). Out of these twelve cultural villages, the three villages of Gamolle, Fasha, Lower Dokatu, and the karat town were purposefully identified and selected for this study. The criteria used for the selection of the sampled villages and the Karat town where the indigenous knowledge practices, values, and rituals observed, the availability and quality of cultural heritage resources to be visited, their proximity and accessibility to the tourist route and larger estimated number of tourists visited these sites. Moreover, the provision of tourist accommodations and services, relatively better infrastructure development, and the relatively larger number of the local community members engaged in the tourism activity, presence of hotels and loges were also the other criteria used for the selection.

The number of participants was thirty six, and it was small because in a qualitative research, it is recommended that the number of participants should be limited to easily manage the process of data collection, transcription, and reduce the complexity of the data analysis. The real names of these participants were changed into letter and number codes (pseudonyms). Therefore, out of these thirty six research participants selected in this study, 28 (about 78 percent) were men and the remaining 8 (about 22 percent) were women. Among these participants, twenty four local community members were involved in key interviews and focus group discussions conducted at the grassroots level in the three sampled cultural villages and the Karat town. Four out of the twenty four of them were experienced, local community elders. The local elders were all male elderly residents with the age ranging between 55 to 74 years old. The elders were members of the Konso community by birth and brought up and have lived almost all of their living in the study area were involved and participated as key interviewees. The codes or pseudonyms used to represent them in the analysis section shall be key interviewee 01, 02, 03, and 04 for elders from Karat town, Gamolle, Fasha, and Lower Dokatu cultural villages respectively.

The other twenty local community members participated in the Focus Group Discussions (FGD) organized into four groups containing five members each, representing Karat town, Gamolle, Fasha, and Lower Dokatu cultural villages. The focus group discussion participants were involved in different tourism activities such as tourist guides, cooks, receptionists, managers, waiters and waitress, guards in hotels and lodges, shopkeepers, tourism product producers and sellers, boiled coffee sellers, and Bajaj taxi drivers, in which their livelihoods predominantly depended upon the tourism activities. Their age varies from twenty to fifty five years old. Pseudonym codes were provided for Karat town Gamolle, Fasha, Lower Dokatu as FGD 01, FGD 02, FGD 03 and FGD 04, respectively. However, sometimes, the individual opinion of the focus group participant was quoted separately in the analysis.

Furthermore, six tourism experts (six of them were men) from the government, culture and tourism agencies at Woreda/Zonal, regional and federal levels were also involved and represented by WCT/ZCT expert 01 and WCT/ZCT expert 02; RCT expert 01 and RCT expert 02 and FCT expert 01 and FCT expert 02, respectively. Age wise, they were 28 to 54 years old. In terms of educational status, their level of education was a first degree and master's degree levels with work

Experiences ranging between 8 and 29 years of service. Three men private investors or managers with the age of 45 to 60 years old, who were engaged in hotel and lodge business accommodations and services were also included. They have also contributed to creating favorable conditions for the Konso local community in the conservation and employment opportunities. They were represented by the codes as OL 01 and OL 02, and OH 01, where OL stands for owner of lodges and OH for owner of hotels.

Lastly, three international tourists (two men and one woman aged between 45 and 70 and speaking the english language) were included as interviewees while visiting the Konso cultural landscape sites during data collection. The international tourists involved in this study were coded as IT 01, IT 02, and IT 03. In general, the actual names of all the research participants involved in this study were changed into mix of letters and number as pseudonyms in the analysis sections to keep the confidentiality of those participants involved in the study.

Data analysis

The data generated from primary data sources, in-depth interviews, FGDs, and personal field observations were analyzed through qualitative explanatory and exploratory as well as content analysis. The data were transcribed, organized and thematically coded for analysis. Whereas, the secondary data collected from various sources were also analyzed through descriptive methods. Content analysis is the process of categorizing verbal data to classify, organize and summaries the data.

Discussion

The Konso Indigenous Knowledge practices as a response to hardship environment

The interaction between human beings and nature was started before several million years ago when human being was created [13]. Knowledge could be created, conserved, and transferred in two ways, in traditional or informal ways and modern scientific ways. Indigenous knowledge denotes the unique traditional knowledge which could be created by a particular group of people or community in a defined geographical area. Scholars such as Siambombe, et al. explain IK as identical with local or traditional knowledge, in which persons in the society comprehend and accomplish practices for generations that evolved by trial and error mechanisms. Those community members involved in the explicit knowledge transfer would operate and continue to live on the landscape they have settled.

In line with this notion, the Konso community’s indigenous knowledge has been created and transferred using these tacit knowledge and explicit knowledge creation and transfer. These indigenous knowledge practices could disseminate based upon the Rogers innovation diffusion theory that explains ideas, practices, or objects created in one original place gradually spreading within a community or a society. Thus, the tacit knowledge is covert, individual and family based, but the explicit knowledge is socially transferred, verbalised, and codified through communal activities in the Konso community.

Indigenous knowledge practice has different meanings and interpretations to different community members. A 65 years old key informant interviewee explained the indigenous knowledge of the Konso community as the skills, wisdom, and practices that we inherited from our ancestors that they had developed in the course of solving the problems they faced in their day to day life as a means of survival without joining modern schooling that eventually we inherited and conserved.

In short, the persistent struggle against the bio physical and cultural environment as a means of survival enabled the Konso community to discover new techniques of production, governance systems and many more. The ancestors of the Konso community had created practicebased knowledge obtained through tacit, explicit, and socialization techniques as their survival mechanisms through adaptive as well as coping strategies.

The tangible and intangible heritage resources of the Konso community

The key interviewees and the majority of the focus group discussants categorized the outcomes of the indigenous knowledge practices of the Konso community as our indigenous knowledge practices, values, and rituals are broadly classified under the following categories of heritage resources: (i) Construction of dry stone walls, agricultural terraces to conserve resources, mora, ponds; (ii) Production of wooden statues, steles, generation transfer poles; (iii) Traditional governance and conflict management systems that imposed sanctions and restrictions upon individuals who violated the values and customs of the community; (iv) Celebration of ritual ceremonies and (v), Preparation of traditional medicines and mummification techniques

Almost all research participants reported that the Konso community members immersed themselves in adopting agricultural terracing techniques in the stony and steep slope topography to conserve soil, water, and forest resources. They have also produced different agricultural household tools (double sided pointed hoe) compatible to the terrain, increasing yields through using natural fertilizers (animal dung), and harvesting rainwater in to ponds to overcome water scarcity.

Unique values of the Konso community

The Konso community has shared several values of the national values of the country as the community being the sub set of the people of Ethiopia. Accordingly, the elders who took part as interviewees in this study asserted the unique values of the Konso community as the prevalence of strong and well regulated communal hardworking cultures and collaboration among the community members, devotion and commitment to improving our livelihoods, social solidarity, and trustworthiness have been some of the main values of our community. Respect for guests, women, and the elderly, giving the real witness, integrity, and forgiveness are the other positive values of our community. Moreover, deception or fraud, stealing, robbery, and theft among community members are strictly forbidden.

These and other attributes of the community enabled the community to have strong community cohesiveness to engage in inter generational conservation of heritages, keeping the rituals and the protection of scarce resources, including agro ecosystem resources such as soil, water, forest resources, and skills as well as tools and objects that had been conserved and transferred to the next generations.

The key interview participants and focus group discussants involved in this study showed that the tangible and the intangible heritages of the Konso community. For instance, interviewee 01 has described them as follows our heritages are highly linked with the day to day life of our community. These include the agricultural bench terraces, the dry stone walled circular cultural villages, usually made from stones, wood, and grasses; the wakas or anthropomorphic wooden statues, the mora or public meeting houses, the generation transfer poles, various agricultural implements, traditional weapons including shields, spears, arrows, and bows. Moreover, rainwater harvesting ponds, museum in which the past objects are collected and displayed, the history and different tools used by our fathers, dressing styles, sacred forests, mummification techniques, erected steles at burial sites are the dominant tangible heritages of our Konso community resulted from IK.

The interviewees and focus group discussion participants also added that the intangible heritage resources of the Konso community incorporate there are traditional governance, mediation and conflict resolution systems, traditional beliefs, various rituals and ceremonies celebrated. These include mana or burial ceremony of the Konso ritual chiefs or poqqollas (tuma), shailita or burial ceremony organized for aging men and women with the age beyond 65 years, mostly when grandfathers and mothers retired or died, instead of crying people at this moment are dancing and singing songs. Two types of poqqollas are common poqqolla tuma, who is separately living in or around sacred forests. A special burial ceremony is arranged for him when he dies. When the poqqolla mugulla in cultural villages dies, the burial ceremony is performed like any ordinary man in the community. The other ceremony is Hora or annual celebration of prayer at each village for peace, rainfall, prosperity, fertility, and this is usually done before starting agricultural activities.

Generally, the Konso community has had immense tangible and intangible cultural heritage resources that resulted from IK. These resources are preserved and conserved for the benefit of the local community, the private sector, and the government. These cultural heritage resources, therefore, attract both international and domestic tourists and accelerate the development of the tourism industry in the area.

The emergence of cultural tourism in the Konso area

The Konso community is one of the indigenous communities in South-western Ethiopia where early cultural tourism emerged. The enabling conditions for the commencement of tourism in the Konso area were the presence of rich heritage resources that resulted from indigenous knowledge practices, values, and rituals of the community. Furthermore, the Konso area has become the only gateway for the entrance to the different pastoral communities further in the South Omo areas.

A 65 and 57 years old local elders who took part as key informant interviewees compared and reported that the situations at the beginning of tourism development, the early host guest relationships by comparing the past with the present in the Konso cultural landscape as initially when foreign tourists came to the Konso cultural villages, some of the Konso native adults and children were hiding themselves from these tourists and their cameras and tried to stare from where they were concealed. Conversely, these days, the community members are very friendly with tourists, and children are carrying baggage for tourists and asking for money and materials such as pens, pencils, and candies. In the past, the cultural heritage sites to be visited were very small; there were no hotels and lodges providing services to the tourists, local tourist guides, gas stations, and convenient roads for travelling within the cultural villages. But now, the number of visitors, services offered, and host guest relations drastically increased. Things were improved, but they were not enough.

This infant stage of tourism activities in the Konso area can be associated with the first stage of Butler's Tourism Area Life Cycle model (TALC) of the Exploration where there were a small number of the tourists (drifters) visiting the site with almost no host-guest relationships. Besides, there were no tourist facilities, accommodations, and services in the Konso area. Not much was known about the tourism activities and even the revenue obtained at the initial stage of tourism development in the Konso area.

Major heritage resources attracting tourists in the Konso world heritage site

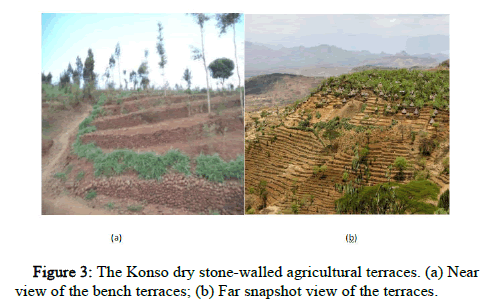

Dry stone walled agricultural terraces (kabata): Historically, the Konso community is an agricultural community along with eyecatching handicraft skills that consists of stone, wood, weaving and metal works. Building agricultural terraces is not only a major manifestation of the Konso community but also it has become the basic livelihood and survival issue of every household. The agricultural activity enables the farmers to gain economic benefits and improve their skills as well as change the interaction modes of their life and thoughts.

According to the Ethiopian environmental protection authority, about 75 to 80 percent of the Konso highlands are contoured by the dry stone terraces [14]. The height of the terraces varies from 0.5 meter to 1.5 meters and the square basin, between two terraces. It has high edges to retain and conserve rainwater. Different annual and biannual crops are grown in the basin; whereas perennial plants like Moringa and coffee are planted at the base of terraced walls. In the Konso terraced fields, multiple cropping, agro forestry, mulching, and irrigation systems are widely practiced to increase household yields sustainably (Figure 3).

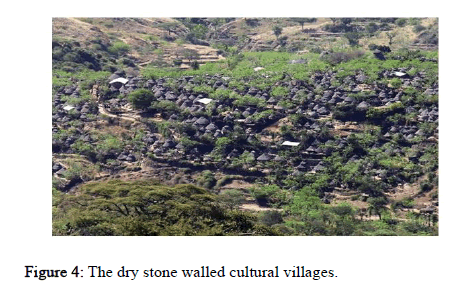

The walled cultural villages the paleta: The dry stone walled cultural villages, the paletas, as the major heritage resources in the Konso cultural landscape are another most important manifestation of the Konso community in attracting tourists. These walled villages are located on the gentler slopes of the Konso highlands strategically established as a fortification or defensive significances against enemies. The structural arrangement of each cultural village is categorized into wards. Wards are again divided into fenced family compounds. The ward members in the cultural villages have mutual assistance and support to one another and this encourages the socio culturally regulated workgroups. These cultural villages were governed by an elected council of elders and served as a judicial body. They are supported by the warrior age grade for arresting and punishing the wrongdoers. However, this traditional system of governance in the walled cultural villages has been weakened after the government change in 1974.

The morphology of the settlements follows some sort of evolutionary processes, in which the old ones are found at the center and the younger being located in the peripheries depending upon increasing in the number of both households and the entire population. It is only the eldest son of the family who is left in the compound inheriting the property of his father, while all the younger sons are obliged to construct their own homestead in the peripheries of each cultural village. One of the dry stone walled cultural villages is indicated in Figure 4.

These settlements are encircled again with several rounds of walled fences, on average from one to 7 rounds. Within these cultural villages, there are narrow paths to which people and animals move. The Moringa tree (having cabbage like leaves), which is planted by the villagers in their compounds, is one of the most important food items and herbal medicines [15].

The indigenous knowledge practices of the Konso community focused mainly on the use of stone for multifaceted purposes. One of the local elder research participants reported that stones are our vital resources and have many different advantages in our community since the time of our forefathers. They are used for building walls of our huts and fences, agricultural terraced fields, and erected steles. Furthermore, the stones are also used as a swearing oath before the wrongdoer for proofing his innocence; used to prove manhood, sharpening ritual spears and knives before hunting, used as stools for sitting inside moras and many more uses

The Konso cultural villages along with many other heritage resources have been the main tourist sites that attract several domestic and international tourists. This is because many of the tangible and intangible heritage resources are within the villages where tourists are also highly crowded during peak seasons.

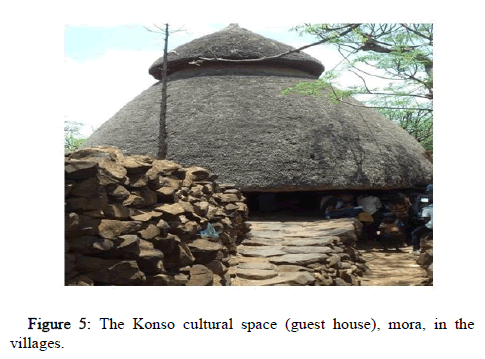

The cultural spaces (the moras): The community guest houses or the cultural spaces, which the Konso called moras have been constructed in the central parts of each cultural village. The moras have multifaceted roles. Primarily, the moras are serving as public spaces for sleeping, where the Konso men stay and pass the nights to easily safeguard the villagers from any kind of attack and threats such as fire accidents and thefts. One of the key interviewees reported that the youngsters have passed nights regularly in the moras with close supervisions of adults whose wives gave fresh babies. This is because in the Konso community husbands whose wives gave fresh babies do no pass nights in the houses with their wives up to three months.

Passing nights every day at moras is a great opportunity for the youngsters to learn from adults and share experiences among themselves for their future life. The moras have also served as centres for negotiation and resolving conflicts in the villages. The community discusses different issues such as fertility and family planning issues. And it is also a place of recreation and relaxation in playing traditional games, tomatasha, chatting, and dancing. These public spaces are also used as stay places for accommodating any male guest coming from other villages of the Konso community (Figure 5) [16].

Therefore, the double thatched moras as heritage resources have become still one of the most interesting tourist attracting sites within the Konso cultural landscape. Foreign and domestic tourists, particularly university students and researchers also frequently visit the mora and other heritage resources in the Konso area.

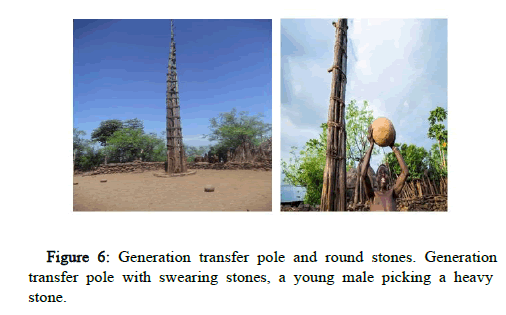

The generation transfer pole (olayta) and round stones: Erecting the generation pole is the other impressive and alive heritage resource of the Konso community which is transferred from generation to generation. This ritual ceremony takes place every 18 years, marking the end of the first generation and the beginning of a new generation. This means, according to the Konso community, one generation is equivalent to 18 years. In the process of erecting the generation transfer pole, when the man in the community is over the age of 52, a stele (dhaga-khela) is erected instead of a juniper pole [17].

One of the key informant interviewees explained that the generation transfer pole is erected to celebrate the generation grade (khela) transfer of man's power in the Konso community. However, this generation transfer pole (khela) along with its ceremonies has totally ignored the equality of women of the Konso community. This is because there is no involvement of women in the activities taking place in mora or guest houses; in the generation power transfer, or the age grading ceremonies (the Kara ceremony).

In the same area with the mora and generation transfer pole within the cultural villages, there have also been two important round stones placed at the same site used for different purposes. The first one is manhood or Dhega-dhiruma used to check whether or not a young male is ready for marriage. The second round stone is a swearing stone when wrongdoers of the community members are caught making an oath to testify their blamelessness before the local elders who tried to manage conflicts among individuals in the community through traditional governance arrangements. The generation transfer pole along with these stones is indicated in Figure 6.

In the open dancing field, during ceremonies, there is a generation transfer pole together with manhood checking stone (the bigger one) and a swearing stone (smaller ones). A young man shown in Figure 5 is not a basketball player who targets the ring on the board, but he is proving his eligibility for manhood by picking the heavy stone at the dancing field near moras and the generation transfer pole. Hence, among the many cultural heritage resources of the Konso community, the generation transfer pole with the stones also attracts the attention of tourists.

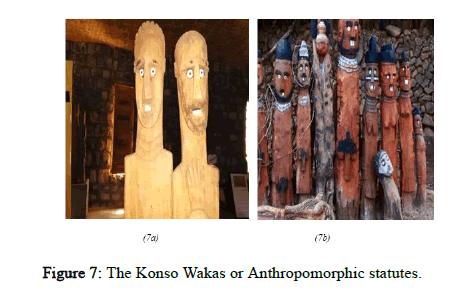

Anthropomorphic wooden statues (waka): The wooden statues, Waka is one of the unique heritage resources which are produced by the indigenous knowledge practices of the Konso community to symbolize different ways of life of the community. These wooden statues are mainly made from juniper trees, which are not easily damaged by termites. Among many different anthropomorphic statues made by the Konso community, Figure 7 symbolizes a male Konso Hero (right) with his wife (left) and a family member who died of diseases.

They have usually been erected on the graves of the outstanding and eminent Konso men such as the heroes, clan chiefs, or poqolla to commemorate their heroic achievements and contributions to the community. The wake of the heroic men, their wives, and weapons used to kill (shields and spears) and animals killed have been erected at the same time. Therefore, these architectural wooden designs of the Konso community have also become one of the most important heritage resources, attracting the attention of tourists visiting the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site [18].

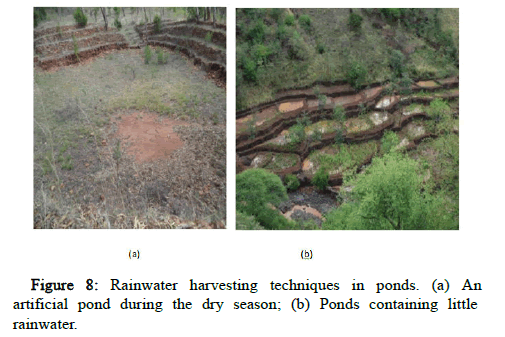

Rainwater harvesting technique in the reservoir (harda): The Konso community has also good indigenous knowledge and skills in handling rainwater and using it during the dry seasons. Rainwater harvesting and effectively using for different purposes is a long tradition among the Konso community. This is mainly because water scarcity is the major problem in the Konso highlands. Getting water for drinking, washing, animals, and irrigation is difficult in the Konso area since the area is located in the arid rift valley section of Ethiopia. The Konso rainwater harvesting techniques are depicted in Figure 8.

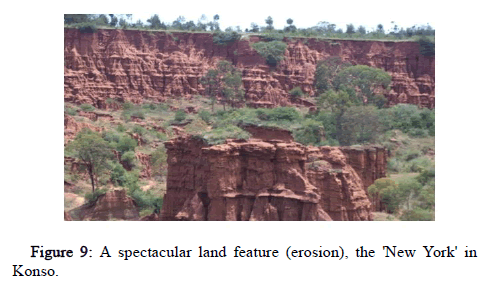

The 'New York' in Konso area: Indeed, 'New York' is the nickname given to one of the spectacular land features resulted from long processes of erosion in the Konso cultural landscape of Ethiopia. However, this spectacular land feature is not connected to the Konso indigenous knowledge system of engineering techniques. Even, there is no physical association between the 'New York' of Konso and the New York City in the United States of America.

Of course, the basic insight behind is the similarities in the structure of pillars which resulted from the erosion process with the view of high rocketing buildings of New York City. The majority of the local community members do not have an idea about the similarities between the two structures. However, they have their own legendary justifications why and how such a landscape is formed. Although this landscape is not the result of the socio-cultural fabrics of the Konso community, it is frequently visited by tourists and remained as one of the most tourist attraction spots in the Konso area near the Fasha cultural village (Figure 9).

Inevitably, changes in the social, economic, cultural, and environmental conditions are expected to occur in UNESCO recognizecworld heritage sites across the world. This happens because tourists would be more secured and confident to visit the sites. The host governments also provide attention to receive tourists at their destinations. This is also true in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site which UNESCO recognized as a world heritage site in 2011. As a result, the social, economic, and cultural changes exhibited in the Konso area in the pre and post inscription periods is greatly differed in the site (Figure 10).

One of a tourism experts interviewed who was working in Konso administrative zone culture, and tourism department reported that there is a big difference in the number of tourist arrivals; tourism related institutions such as tourism offices, hotels, lodges and gas stations in providing accommodations and services in the Konso cultural landscape. Although very recent, tourist flow has gradually grown and revenue generated increased, tourism sector related institutions have been flourishing in the Konso area and some of our youngsters have been employed in different tourism activities. However, the number of young people involved and benefited in different tourism activities in the Karat town exceeds those in the cultural villages of Gamolle, Fasha, and Lower Dokatu cultural villages. This is because there is a good number of tourists stay in the Karat town and the lodges found in its outskirts and most educated youth are found in Karat town.

According to the observation made by the author, the Konso Zone culture and tourism department, the konso cultural landscape world heritage information center, the ata tour guide association, the Konso cultural museum, the Konso cultural center, and culture and tourism committee at cultural villages have been established as tourism structured institutions in the Konso area. Moreover, hotels and lodges such as Kanta lodge, Konso korebta lodge, and strawberry fields eco lodge, and Konso edget, green and saint mary hotels have also been constructed in and the outskirts of Karat town to provide services and accommodations to the tourists. Following this, the local community has begun to be employed in these tourism agencies, institutions, lodges, and hotels and get access to job opportunities to enhance their livelihood basis and reduce food insecurity. Although there was a fluctuation in the number of employees hired in the lodges and hotels, there was an increasing trend in the provision of services and accommodations year after year in Karat town and its surroundings [19].

Social and economic contributions of tourism

Comparatively speaking, among the population of the Konso cultural landscape, very a small number of residents are involved in the tourism activities. This means cultural tourism has created limited employment opportunities for local community members, predominantly the young people. The two of the FGD participants at Karat town (FGD 01) and Gamolle, cultural villages (FGD 02) for example reported that the majority of us graduated our secondary school education and sitting idle before. However, now we have been involved in different tourism activities to improve our income sources and livelihoods. These include traditional handicraft production, such as shirts, shorts, scarves, making 'models of cars, and ships'. We have also made bracelets from silver and other materials and selling them to the tourists. Still, some of us employed in the lodges and hotels as guards, waiters, and waitresses; serving as tourist guides; preparing and selling foods and beverages to tourists.

However, the involvement of the local community members in different tourism activities was not only spatially varied between the Karat town and the Gamolle, Fasha and Lower Dokatu cultural villages but also differed in the number of people who were engaged in the scale of decision making. Moreover, the benefits obtained from tourism related activities hardly trickle down to the Konso community members, the poor in the cultural villages as the multiplier effects in diversifying their livelihood assets.

A twenty eight years old female, widowed focus group discussant at Karat town who was leading her living by making and selling coffee in her small house along the roadside reported that there are tourists and their drivers who have enjoyed drinking coffee that I used to make and this generates income to support my family and myself. With the income I have generated selling coffee and breakfast, I buy basic household equipment, food items for my family and pay school fees for my two children, medical treatment fees and cover other minor expenses.

About employment opportunities created by cultural heritage tourism, the FGD participants also asserted that after taking short term tourism based training, we directly joined the ata tour association as tourist guides and Konso crafts center to provide tourist services in the Konso cultural world heritage site. We have benefited a lot from it. However, the income that we get from tourism is greatly fluctuating between big and low seasons. Our income is determined by the number of tourists visiting the Konso cultural landscape. However, the English language and handicrafts skill development trainings we have received are insufficient to give better services.

A few of the young people who are employed in the different service providing institutions such as lodges and tour guide association improved their living. One of the FGD participants (FGD 01) who was hired in one of the lodges said that I was employed in a lodge some seven years ago as a receptionist. And now I am working as the supervisor of the lodge. During my stay at the lodge, my living has been improved in many ways. I obtained lots of work experiences and skills such as handling customers, or tourists effectively, communication, good relationships and how to manage human behaivours. Besides, I have received my bachelor's degree in management through distance learning and my salary has increased. In that, I am supporting my poor parents.

The owners of lodges and hotels who have invested on the provision of services in the tourism sector in the Konso area supported the local community members in employing in different activities. One of the owners of a lodge near the Karat town expressed that the majority of the workforces we employ come from the local community. Starting from the time of the construction of the lodges until now, some local community members have been involved as a permanent and temporary workforce. Among these activities, building cultural huts in the lodge compound, cleaning bedrooms and offices, cultivating vegetables and rearing animals in the backyard of lodges, and working as janitors, cooks, guards, waiters, and waitresses.

The total number of domestic and international tourists who visited the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site and the corresponding revenue generated from the tourists from 2007 to 2020.

As it depicted in Table 1, the tourist flow and the revenue collected from cultural tourism in the Konso area showed a fluctuating trend. The maximum number of tourists visited and the revenue generated in the Konso cultural landscape in 2017/2018 was 16,044 tourists with total revenue of ETB 2,331,860 (USD 84, 487). The year 2017/2018 marked the highest record in both tourist flows and revenue generation in the South Regional State and the Konso area mainly because of the relative peace and security seen and large number of Ethiopian diasporas living abroad came back to their country and visited these tourist destinations. However, in 2019/2020, tourist flow and revenue obtained drastically declined as a result of the political instability and ethnic turbulence followed by the declaration of state of emergency in the South region and the expansion of COVID-19 pandemic [20].

| Years | Number of Domestic &International Tourists | Revenue Generated | Average Exchange Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ETB | USD ($) | |||

| 2006 /2007 | 6,151 | 109,282 | 12,561 | 8.7 |

| 2007/2008 | 4,968 | 267,050 | 28,715 | 9.3 |

| 2008/2009 | 5,826 | 343,702 | 34,717 | 9.9 |

| 2009/ 2010 | 11,851 | 513,304 | 44,250 | 11.6 |

| 2010/2011 | 12,176 | 508,073 | 30,063 | 16.9 |

| 2011/2012 | 15,265 | 799,491 | 45,168 | 17.7 |

| 2012/2013 | 15,363 | 1,434,911 | 76,733 | 18.7 |

| 2013/2014 | 10,999 | 2,012,317 | 102,668 | 19.6 |

| 2014/2015 | 11,931 | 1,093,642 | 53,089 | 20.6 |

| 2015/2016 | 4,933 | 454,352 | 20,841 | 21.8 |

| 2016/2017 | 12,182 | 1,487,858 | 62,253 | 23.9 |

| 2017/2018 | 16,044 | 2,331,860 | 84,487 | 27.6 |

| 2018/2019 | 14,571 | 1,974,928 | 67,634 | 29.2 |

| 2019/2020 | 5,874 | 674,451 | 19,325 | 34.9 |

| Total | 148,134 | 14,005,221 | 682,504 |

Table 1: The Tourist arrivals and revenue obtained in the Konso cultural landscape.

The revenue generated from the tourists who visited the cultural villages was collected and shared based on the proclamation No. 141/2012 of the Southern nations, nationalities and people's regional state and the financial regulations under the supervision of the culture and tourism bureau of the region.

The culture and tourism experts who participated as interviewee from the Konso Woreda/Zone and Southern regional state reported that the revenue collected is shared yearly in the ratio of 70 to 30 basis,which means, 70 percent of the amount collected from the tourists was equally distributed to the twelve cultural villages of the Konso cultural landscape recognized by UNESCO and the Konso cultural museum. Although limited, the shared amount of money among the cultural villages was used to maintain the cultural heritage resources, including the moras, and used for other infrastructural development, such as building schools, laboratories, libraries, and potable water services to the local communities in the UNESCO recognized villages. The remaining 30 percent was left in the South regional state culture and tourism bureau, which is used for culture and tourism activities such as providing training, tourism advertisements, and other tourism promotional works.

Factors deterring the involvement of the local community in to cultural tourism activities

The involvement of stakeholders in the tourism sector greatly varies from destination to destination in the tourist attraction centers. Based on the information obtained from key informant interviewees, FGD participants, and observation made by the author, the involvement of the local community in tourism activities were affected by several factors. Among these factors, the major ones are

Proximity versus remoteness distance factor: Tobler's first law of geography states that 'everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things'. This means the interaction between places shrinks in strength and frequency as the distance between them extended.

Literacy versus illiteracy: Relatively speaking, educational background matters in tourism development. Elites or educated residents have a greater chance of being involved in tourism activities than those who are illiterate. As it has been observed from FGD during data gathering periods in the sampled cultural villages of Lower Dokatu, Gamolle, and Fasha, villages, including the Karat town, educated persons have better opportunities in running tourismbased businesses, being employed in government culture and tourism agencies, lodges, and hotels as well as employed as tourist guides.

Age, sex, and disability: Adults are eligible and have a relatively better possibility of being involved in tourism activities than children, the elderly, and the disabled persons in institutions such as lodges and hotels. Thus, most of the community members who have been involved and benefited from cultural tourism in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage sites were younger men and a smaller number of women. Socio culturally, rural and uneducated women are not encouraged to be genuinely involved in different tourism activities such as tour guides and receptionists as their male counterparts.

Craft industry: Members of the community who are engaged in the production of different handicrafts produce better and benefit from the tourism activities than those people who are not attached with this informal sector. Weaving, as part of the craft industry, has been well practiced among the Konso community since cotton is widely grown. Wood carvings, basketry, and pottery are also some of the craft industries practiced in the Konso area.

Political attachments: People who have a political attachment to the existing government have a relatively better chance of being involved in tourism than those people and institutions which have little or no attachment to the political system. Particularly, in the past political system of Ethiopia, Ethiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF) favoured party members and supporters more to be employed not only in the tourism sector but also in other sectors to get job opportunities than non-members and members of opposition parties. On the other hand, people without or little expertise are assigned as heads of tourism institutions from local to national levels. Some professionally unfit individuals have been deliberately assigned or appointed as tourism institution leaders by simply looking at their political commitment to the existing political system that eventually harms the development of the tourism because of lack of assigning the right man in the right place.

Factors affecting the overall development of cultural tourism in the Konso area

There many interrelated factors affecting the development of tourism in the Konso cultural landscape heritage site.

Divergence of interests among stakeholders: The level of involvement of these stakeholders in the heritage resource conservation and management as well as the tourism activities and the benefits that they obtain. The local community, the government agencies, the private sector, and the tourists have been involved with different interests that led to conflicts. There are limited collaborations and a lack of integrated efforts over the conservation of IK practices and heritage resources in benefiting from the cultural tourism development. The divergence of interests occurs horizontally, within the community members, or within private investors or local agencies or among all these parties and vice versa. The research participants had explained the role and interests of the local community. For example, in FGD 03, it was explained as our ancestors had paid sacrifices in conserving the indigenous knowledge practices, values and rituals and preserving the heritage resources for hundreds of years. These heritage resources have brought an opportunity for the development of cultural tourism in the Konso area. However, because of the various divergent interests of the community, the private sector, the government and the tourists, the conservation heritage resources faced challenges. This has again harmed the development of cultural tourism that hider us from fairly benefiting from cultural tourism.

According to the social exchange theory, the genuine participation and support of the local community in tourism activity (host guest relations) are determined by the advantages and opportunities that they received from the tourism system. The benefits the local community has received from cultural tourism should be greater than the perceived burdens and costs since the communities are incentive seeking and punishment removing by nature.

The gap between the existing Konso tradition and introduced systems: The exotic elements introduced to the Konso area have been explained by the FGD participants. For instance, FGD 01 explained it as the expansion of introduced christian religion sects and their interventions, the spread of modern education and its imposition on indigenous knowledge practices, value, and rituals; the effects of modern governance system against traditional governance systems; the diffusion of newly introduced modern lifestyles and technologies upon the traditional ways of life of our community have brought impacts on socio-cultural life of the Konso community.

However, few respondents hold the view that the introduced religions, schooling and governance system, new lifestyles and technologies could help the community to transform the traditional way of life to modern life. If the Konso community focuses only on the conservation of IK practices and heritage resources without modern way of life, then it can be separated from the rest affluent societies. For them, keeping modernity is better than losing KI practices, heritage resources and cultural tourism. The author argues that this happens because of lack of integration between traditional and modern knowledge systems. Thus, keeping the middle road should be a desirable option.

Limited collaborations among public and private sectors: The owners of the lodges, the local community members warmly welcome business people at the initial stages. However, the coordination, collaboration and interdependence among stakeholders in the Konso area in enhancing tourism development were insufficient and needs special consideration.

A 45 years old businessman who owned a lodge in the outskirt of the Karat town reported that as a private tourism businessman and owner of a lodge in the Konso area, I have tried to make the tourism activity of the supply side more attractive by providing reliable services and accommodations to our customers in such a rural countryside, where there would be a risk of investment in tourism. However, the commitment and willingness of the local government bodies to support us is limited, and does not meet my expectations. In addition, there is also inadequate collaboration and harmonisation even among us, the owners of lodges, hotels, and other service providers in promoting the tourism industry and conservation of resources in the Konso area.

Based on the information generated from the FGD participants, the key interviewees, and observations made, the following challenges have been identified.

Limited length of stay time of the tourists: There are several factors which push or pull tourists to stay longer or shorter periods at the tourist destinations. The major reasons identified include the low quality of service provision, security problems and frustration, shortage of accommodations during big seasons, small area and sites to be visited in the destination, inconvenience touristic facilities, and lack of preferences and needs of tourists. According to EMoCT, the average length of tourists stay time in Ethiopia is about 16 days. However, the tourists length of stay in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site is not be more than one or two days. The longer the tourists stay at the Konso tourist sites, the more the local community members secure job and generate better income; and the owners of lodges, hotels, and other businessmen can also obtain additional returns.

Seasonal nature of the tourism activities: The tourism industry as a business activity has a seasonal character. There are well defined and favorable seasons and conditions when a large number of tourists visit these attractions, which are said to be peak seasons (big seasons). On the contrary, there are idle (low seasons) seasons when only a limited and small number of tourists visit the sites. Experts in culture and tourism who took part as interviewees in this study confirmed that there are seasonal variations of both the domestic and international tourists to visit the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site. A larger number of international tourists come to the sites from the beginning of December to mid of May. However, most domestic tourists, particularly university and college students come to visit the site from November to mid December and from the beginning of February to mid of May. Cultural villages have been crowded with tourists this time; the amount of revenue generated from tourists also greatly varied depending upon the arrival of these tourists to the site.

Observation was carried out both during peak or big seasons (the time when the larger number of tourists visiting the sites) and the low/ idle seasons (when a relatively small or a fewer number of tourists visiting the sites). It was observed that the lodges had a limited number of beds, food, and drinks that provide services for tourists during peak seasons. When tourists come in a large number, the lodges and hotels could not host the non-booked tourists. However, there had been other hotels that had beds in the Karat town with low quality and below the standard for providing accommodations and services for international and domestic tourists. Even some of the tourists were obliged to drive north wards over eighty kilometres to Arba-Minch town to get such services [21].

In short, the tourist flows into the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site show seasonal fluctuations both in terms of the number of tourists visiting and the revenue collection.

Political strife: Tourism industry is a service providing sector of the economy, which needs the physical presence of tourists to the destination. Thus, tourism is highly vulnerable to social evils such as political instability, civil wars, and pandemic diseases. Moreover, tourism is susceptible to unmanaged sites, hazardous weather conditions, and poor infrastructure development.

One of the key interviewees explained how the political situations in the Konso area affected the development of tourism as in the Konso area, there was an unstable political condition for the past five or more years because of the request of the community for zonal level administration status. However, immediate response was not given by the regional and federal governments. As a result, the conflicts provoked led to loss of life, displacement, and destruction of property. Solution was given lastly to the request of the community by offering zonal administration status. Even after the Konso community got its zonal level of administration in the mid of 2019, the conflict has continued with the neiboughring, Alle community over resources. The unstable political condition had affected the cultural tourism development in the Konso cultural landscape world heritage site.

For instance, one of the owners of a lodge on the outskirts of Karat town reported that “the revenue generated from tourists in August and September 2017 was about 753,000 ETB (31,506 USD) and 510,000 ETB (21,338 USD) respectively. However, in August and September 2018, the revenue obtained was reduced to 430,000 ETB (17,991 USD) and 248,000 ETB (10,376 USD) respectively”. This shows how peace and security are essential for the proper functioning of tourism activities at the Konso tourist site.

Lack of infrastructure and other related threats: During data collection, the internet connections were very poor and tourists did not get adequate services in the lodges. A tourist who was interviewed at one of the lodges in the destination reported that I used to visit some world heritage sites in Africa. In some countries, tourist accommodations and services were better off and in some other sites, it was poor. We plan to stay here for three or more nights. However, we faced challenges during our visit to the Konso World Heritage Site. Lack of getting internet access, poor road accessibility, and lack of getting fuel stations for refueling our vehicles and security problems were some of the challenges we faced. Consequently, we as tourists are temporarily isolated from our families, relatives, and co-workers in our home country because of a lack of internet access. By tomorrow, we will leave the Karat town and go to Arba-Minch town to get the services by reducing our stay time.

One of the tourists who participated in this study also added that the hospitality of the Konso community and some of the things were improved to promote the development of tourism as as we travelled into the villages, the residents have warmly welcomed us showing their smiley faces with a lovely manner. They are very friendly and hospitable. They also show us the narrow paths within the crowded villages and try to help us by carrying our bags and materials... However, children and a few persons are asking us for pens, candies, chewing gum, money, and similar other materials. This may bring negative impacts and shade a bad image on the sites. In general, there is good hospitality, but accompanied by begging.

Conclusion

The Konso community has been engaged in producing, conserving and transferring its indigenous knowledge practices, values and rituals, but rarely integrated into modern skills the traditional knowledge, values and rituals of the Konso community are not in bond with modern education, governance system; the long established cultural heritage resources that resulted from the indigenous knowledge, values, rituals of the Konso community that attracted tourists have been deteriorated due to lack of sustainable conservation efforts. Moreover, stakeholders who are directly or indirectly involved in tourism activities in the Konso area lack collaboration and integration; due to different interests cultural tourism development has brought social and economic changes to the Konso community but limited. The Konso community members are rarely aware of the significance of the cultural tourism activity, and consequently their involvement is limited.

References

- Ghanem MM, Saad SK (2015) Enhancing sustainable heritage tourism in Egypt: Challenges and framework of action. J Herit Tour 10:357-377.

- Richards G (2018) Cultural tourism: A review of recent research and trends. J Hosp Tour Manage 36:12-21.

- Mapara J (2009) Indigenous knowledge systems in Zimbabwe: Juxtaposing postcolonial theory. J Pan African Stud 3:138-155.

- Karbo T (2013) Religion and social cohesion in Ethiopia. Int J Peace Dev Stud 4:43-52.

- Pankhurst R (1999) Ethiopia, the Aksum obelisk, and the return of Africa's cultural heritage. Afr Aff 98:229-239.

- Kidane-Mariam T (2015) Ethiopia: Opportunities and Challenges of Tourism development in the Addis Ababa-upper Rift Valley corridor. J Tour Hosp 4.

- Siambombe A, Mutale Q, Muzingili T (2018) Indigenous knowledge systems: a synthesis of Batonga people’s traditional knowledge on weather dynamism. Afr J Soc Work 8:46-54.

- Ngozwana N (2018) Ethical Dilemmas in Qualitative Research Methodology: Researcher's Reflections. Int J Educ Method 4:19-28.

- Mehta K, Alter TR, Semali LM, Maretzki A (2013) AcademIK connections: Bringing indigenous knowledge and perspectives into the classroom. J Comm Eng Sch 6:83.

- Owusu-Ansah FE, Mji G (2013) African indigenous knowledge and research Afr J Disabil 2:30.

[Crossref] [Googlescholar][Indexed]

- Asmare BA (2016) Pitfalls of tourism development in Ethiopia: the case of Bahir Dar town and its surroundings. Korean Soc Sci J 43:15-28.

- Gobena EC, Gudeta AH (2013) Hotel Sector investment in Ethiopia’. J Bus Manage 1:35-54.

- Amare A (2015) Wildlife Resources of Ethiopia: Opportunities, challenges and future directions: From ecotourism perspective: A review paper. Nat Resour 6:405.

- Mulat Y (2013) Indigenous knowledge practices in soil conservation at Konso People, South Western Ethiopia. J Agric Environ Sci 2:1.

- Adu-Ampong EA (2017) Divided we stand: Institutional collaboration in tourism planning and development in the Central Region of Ghana. Curr Issues Tour 20:295-314.

- Eyong CT (2007) Indigenous knowledge and sustainable development in Africa: Case study on Central Africa. Tribes and tribals 1:121-139.

- Ezenagu N (2020) Heritage resources as a driver for cultural tourism in Nigeria. Cogent Arts Humanit 7:1734331.

- Ferro-Vázquez C, Lang C, Kaal J, Stump D (2017) When is a terrace not a terrace? The importance of understanding landscape evolution in studies of terraced agriculture. J Environ Manage 202:500-513.

- Förch W (2003) Case Study: The Agricultural System of the Konso in South- Western Ethiopia. J Soc Sci 38:185-195.

- Maunganidze L (2016) A moral compass that slipped: Indigenous knowledge systems and rural development in Zimbabwe. Cogent Soc Sci 2:1266749.

- Rössler M, RC L (2018) Cultural Landscape in World Heritage Conservation and Cultural Landscape Conservation Challenges in Asia. Build Herit 3:3-26.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi