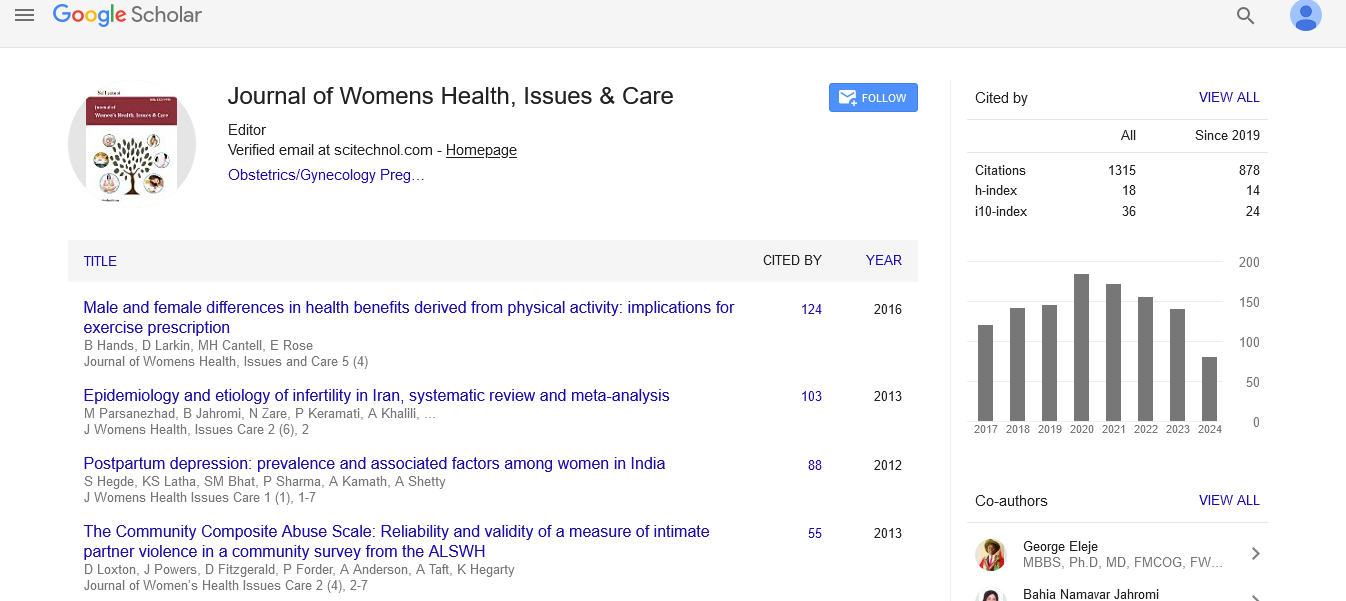

Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 5 Issue: 6

Sex-Based Disparities in the Use and Results of Gastrointestinal Procedures for Workup of Anemia

| Ariela L Marshall1*, Xin Zhang2, Brad Lewis3, Sunanda Kane4 and Ronald S Go1 | |

| 1Division of Hematology, Mayo Clinic Rochester, New York, USA | |

| 2Department of Internal Medicine, Mayo Clinic Rochester, New York, USA | |

| 3Department of Biomedical Statistics and Informatics, Mayo Clinic Rochester, New York, USA | |

| 4Division of Gastroenterology, Mayo Clinic Rochester, New York, USA | |

| Corresponding author : Ariela L Marshall

MD, Mayo Clinic, Division of Hematology, Mayo Building 10th floor, 10-90E, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, Minnesota 55905, USA Tel: (507) 284-8634 Fax: (507) 538-6803 E-mail: marshall.ariela@mayo.edu |

|

| Received: October 03, 2016 Accepted: November 01, 2016 Published: November 05, 2016 | |

| Citation: Marshall AL, Zhang X, Lewis B, Kane S, S Go R (2016) Sex-Based Disparities in the Use and Results of Gastrointestinal Procedures for Workup of Anemia. J Womens Health, Issues Care 5:6. doi: 10.4172/2325-9795.1000249 |

Abstract

Background: Iron deficiency is a common cause of anemia, and etiologies differ by sex. Endoscopic procedures are often utilized to search for a source of gastrointestinal blood loss in patients with iron deficiency, but sex-based differences in patterns of workup have not been well characterized.

Methods: We performed a retrospective review of all patients at Mayo Clinic who underwent esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), colonoscopy, or both between July 1, 2014 and June 30, 2015 for an indication of “anemia” or “iron deficiency anemia” and analyzed the data for evidence of sex-based differences in procedure outcomes.

Results: 999 procedures were performed; 455 (46%) procedures were performed on men and 544 (54%) on women. Median age was 68 years in men (range 19-94) and 64 years in women (range 18-94), P<0.01. 365 (37%) procedures identified a probable benign source of bleeding, 54 (5%) identified a probable malignant source, and 580 (58%) had no findings consistent with a bleeding source. Procedures performed on men were more likely to identify a source of bleeding (48% versus 37%, P<0.01), primarily EGDs which were significantly more likely to identify a bleeding source in men (59% versus 37%, P<0.01).

Conclusion: There are sex-based variations in the utilization and findings of EGD and colonoscopy used for workup of anemia. A source of bleeding is more likely to be identified in men, particularly in the case of EGD. Clinicians should be made aware of these variations and quality improvement programs may be helpful to reduce non-clinically indicated practice variations.

Keywords: Anemia; Iron deficiency; Sex-based variations

Keywords |

|

| Anemia; Iron deficiency; Sex-based variations | |

Introduction |

|

| Anemia is an extremely prevalent condition, affecting over a billion people worldwide and contributing to a substantial percentage (almost 10%) of worldwide years lived with disability [1-3]. Iron deficiency is the most common cause of anemia and is more common in women of childbearing age than other demographic groups. The estimated prevalence in the United is between 9 and 16% in adolescents and women of childbearing age and 5-10% in healthy older adults (over age 65-70) [2]. Iron deficiency anemia is associated with fatigue, decreased work capacity, and decreased scores on cognitive testing [2,3]. | |

| Investigation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract with colonoscopy and/or endoscopy is often performed in patients with iron deficiency anemia to search for source of gastrointestinal blood loss. Nationwide, over 11 million colonoscopies and 7 million endoscopies are performed annually [2,3]. Though the etiology of iron deficiency may be less likely due to GI loss in women of childbearing age due to menstrual blood loss as an alternative source, differences in patterns of GI workup between men and women – including the utilization of GI procedures - have not been well characterized. Given literature demonstrating sex-based disparities in the use of colonoscopy in the setting of colorectal cancer screening [2,3]. It is reasonable to investigate whether such disparities are also present in the case of colonoscopy and endoscopy performed for workup of anemia. As part of a quality improvement project to understand the use of endoscopic procedures in the workup of anemia, we examined sexbased differences in the utilization and outcomes of GI procedures ordered for workup of anemia. | |

Materials and Methods |

|

| Study population | |

| This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota. We performed a retrospective review of all patients at Mayo Clinic who underwent endoscopy, colonoscopy, or both procedures between July 1, 2014 and June 30, 2015 for an indication of either “anemia” or “iron deficiency anemia.” | |

| Data collection | |

| Sources of data included provider notes, laboratory values, procedure notes, and pathology reports. Baseline data included patient age and sex, medical comorbidities including renal disease, liver disease and history of gastrointestinal malignancy, and laboratory values related to anemia (blood count, iron studies, coagulation testing) collected within the four weeks prior to a GI procedure. Procedurerelated data included the type of procedure performed, findings at the time of the procedure (including whether a source of bleeding was found and whether that source was benign or malignant), and procedure-related complications including type of complication and whether the complication required hospitalization. “Benign” conditions were defined as presence of fresh blood or evidence of recent bleeding, ulceration, erosion, active colitis, or large hemorrhoids with no evidence of malignancy on pathology, and “malignant” conditions were defined as abnormalities on endoscopy with a corresponding pathology report confirming the presence of malignancy. | |

| Statistical analysis | |

| Continuous variables were summarized as median (range), and categorical variables were summarized as frequencies (percentages). Differences between genders were tested using the Kruskal-Wallis rank sum test for continuous variables and the Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables. All tests were two-sided, and a p-value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data was entered into an electronic database and data analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel 2010 and SAS 9.4 or higher (SAS Institute; Cary, NC). | |

Results |

|

| Patient demographics | |

| Basic demographics are found in Table 1. Nine hundred ninetynine procedures were included in the analysis, including 224 colonoscopies, 306 endoscopies, and 469 combined colonoscopy/ endoscopies. Four hundred fifty-five (46%) procedures were performed on men and 544 (54%) procedures were performed on women, and procedure type distribution and procedure indication did not vary by sex. Median age at the time of any procedure was 68 years in men (range 19-94) and 64 years in women (range 18-94), p<0.01. Significantly more men had renal disease and a prior history of gastrointestinal cancer than women (16% versus 8%, p<.01 and 7% versus 3%, p=0.02, respectively) and a similar proportion of patients had liver disease (9% of men and 8% of women, p=.33). | |

| Table 1: Patient Demographics by Sex. | |

| Findings at the time of the procedure | |

| Findings at the time of the procedure are found in Table 2, including whether or not a source of bleeding was identified and whether that source was benign or malignant. Overall, 365 (37%) of procedures identified a probable benign source of bleeding, 54 (5%) identified a probable malignant source, and 580 (58%) had no findings consistent with a bleeding source. Procedures performed on men were more likely to identify a source of bleeding (48% versus 37%, p<0.01). These findings depended on procedure type: colonoscopies were not significantly more likely to identify a bleeding source in men (36% versus 29%, p=0.28), endoscopies were significantly more likely to identify a bleeding source in men (59% versus 37%, p<0.01), and combined procedures were somewhat more likely to identify a source in men (48% versus 40%, p=0.06). | |

| Table 2: Procedure results based on Sex. | |

| Procedure results based on pre-procedure documentation status | |

| Procedure findings (no source of bleeding, benign source, or malignant source) based on pre-procedure documentation status (anemia or iron deficiency) are identified in Tables 3A and 3B, respectively. For those procedures performed for an indication of “anemia” women were more likely than men to have documented anemia prior to procedures which did not identify a source of bleeding (64% versus 46% p=0.01). There were no sex-based differences in preprocedure anemia documentation rates for procedures performed for “anemia” which did identify a source of bleeding, whether benign or malignant. For those procedures performed for an indication of “iron deficiency anemia,” we examined documentation regarding iron deficiency (rather than iron deficiency and anemia) prior to the procedure. Women were more likely than men to have documented iron deficiency prior to procedures which did not identify a source of bleeding (54% versus 39%, p for trend=0.02). Women were also more likely to have documented iron deficiency anemia to procedures that identified benign sources of bleeding (52% versus 35%, p for trend=0.01), and there were no sex-based differences in pre-procedure documentation rates for procedures which identified likely malignant sources of bleeding. | |

| Table 3A: Sex-Based Procedure Results for Anemia by Documentation Status. | |

| Table 3B: Sex-Based Procedure Results for Iron Deficiency Anemia by Documentation Status. | |

Discussion |

|

| Research regarding sex disparities is extremely important in identifying biological and socio-demographic variations in clinical care and developing potentially high-impact targets for improvement of care processes and health care systems as a whole [2]. In this study, we identified several sex-based differences in the utilization and results of colonoscopy and endoscopy for the workup of anemia. Almost 1000 GI procedures were performed at our institution between 2014 and 2015 for an indication of “anemia” or “iron deficiency anemia”. Women undergoing these procedures were on average younger and had less medical comorbidity than men. GI procedures (particularly endoscopy) were more likely to identify a source of bleeding in men compared to women. Conversely, pre-procedure anemia and iron deficiency were more often appropriately documented in women than men for those procedures that did not identify a GI source of bleeding (indicating that despite higher rates of appropriate documentation in women compared to men, a source of bleeding was still less likely to be found). | |

| These findings correlate with the known causes of iron deficiency in the United States. Iron deficiency is more common in women of childbearing age and, in this population, iron deficiency is most often due to menstrual blood losses, pregnancy, and in some cases insufficient dietary intake [2,3]. These etiologies would not be expected to have a “positive finding” at the time of an endoscopic evaluation. However, in men, iron deficiency is more often due to gastrointestinal blood loss and therefore our finding that endoscopic procedures were more likely to identify a source of bleeding in men is not unexpected [4-8]. | |

| To our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of sex-based disparities in use of endoscopic procedures for evaluation of anemia. While some – but not all – prior studies have identified lower utilization of sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy in women compared to men when used for the purpose of colorectal cancer screening [9,10], we are not aware of reports in the literature regarding sex disparities in procedural workup of anemia. Additional strengths of this study include the large number of procedures performed, the availability of full records for each procedure (including procedure notes and pathology reports) allowing for complete documentation of procedure findings, and the diverse population of patients undergoing procedures - including patients from a wide variety of age groups and with different medical comorbidities – which increases the generalizability of these findings [11-13]. | |

| The limitations of this study include its retrospective design and the nature of documentation in terms of indication for procedures. Inherent to any retrospective study is potential selection bias regarding the patients included in the analysis, though in this case the group of patients undergoing colonoscopy and endoscopy was quite large (almost 1000) and included all patients within a 2-year period without any specific selection criteria other than indication for procedure, thus minimizing most potential sources of bias. | |

| It is certainly possible that the documented indication of “anemia” or “iron deficiency anemia” was not fully reflective of the physician’s specific reason for ordering a procedure. Physicians may feel in their clinical judgment that a patient has specific risk factors or “red flag” symptoms that merit endoscopic evaluation but that may not have a corresponding specific indication in the list from which they are provided when ordering a procedure. They may instead pick an indication (such as “iron deficiency anemia”) which would be reasonable but not precisely correspond with the clinical indication for the individual patient. In this case, failing to identify a source of bleeding during the procedure would not be a true “negative” result if the procedure was not, in fact, performed with the intent to look for a bleeding source. Additionally, it is possible that women with iron deficiency anemia previously underwent additional workup for other sources such as gynecologic blood loss without positive findings, providing a pre-procedure sex-based difference in prior level of evaluation [14,15]. Finally, patient preferences and level of anxiety – including strong wish to undergo a procedure for workup of either symptoms or laboratory findings for which workup has not yet identified a source – are extremely subjective and difficult to document. | |

| Our research has demonstrated differences between men and women in terms of utilization and outcome of endoscopic workup of anemia. One important finding from this work is that procedural workup – particularly EGD – is less likely to identify a source of gastrointestinal blood loss in women compared to men. Multiple factors are involved in the decision for a provider to recommend such workup, and given that endoscopic procedures carry a small but clinically significant risk of complications such as perforation and bleeding, it is essential that providers have a detailed discussion with patients about the relative risks and benefits of such evaluation. Documentation of prior workup, including hemoglobin and iron stores (to ensure that a patient truly meets criteria for “iron deficiency anemia”) is essential. Additionally, providers should document specific symptoms (abdominal pain, reported blood in the stool) and potential other sources of blood loss, with an attempt to quantify blood loss if possible, such as with the pictoral blood loss assessment chart [2]. Future research has the potential to identify characteristics of patients – for example, young women with no “red flag” gastrointestinal symptoms and high menstrual blood loss – who may not benefit enough from endoscopic evaluation of iron deficiency anemia to warrant the risks of undergoing the procedure. | |

Conclusions |

|

| Endoscopic procedures (colonoscopy and upper endoscopy) are frequently used in the workup of anemia, ideally to identify a source of bleeding in a patient with iron deficiency anemia. In reviewing almost 1000 procedures performed with a documented indication of anemia or iron deficiency anemia, we found sex-based disparities in patient characteristics and procedure findings. Women undergoing procedures were younger, less likely to have medical comorbidities such as renal disease or known history of gastrointestinal malignancy, and also less likely to have a “positive finding” (potential source of bleeding) identified during the procedure (particularly upper endoscopy) despite higher rates of appropriate documentation of anemia prior to the procedure. Providers should be aware of these disparities and take them into account when counseling patients about undergoing procedural workup of anemia. Further research may be able to identify subgroups of patients who could avoid the risks of endoscopic workup without significant risk of missing an endoscopically-detectable source of bleeding. | |

Acknowledgments |

|

| This work was supported by a Mayo Clinic Department of Medicine Quality Improvement Award. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi