Case Report, Clin Oncol Case Rep Vol: 6 Issue: 2

Primary Undifferentiated Neoplasm of the Left Arm with Characteristics of Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumor and High-Grade Sarcoma

Rodrigo Paredes de la Fuente1, Megan E Anderson 2,Mary Linton B Peters1*

1Department of Medical Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215, United States

2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston MA 02215, United States

*Corresponding Author: Mary Linton B Peters

Department of Medical Oncology,

Beth Israel Deaconess, Medical Center, Boston, MA 02215, United States.

E-mail: mbpeters@bidmc.harvard.edu

Received: February 02, 2023; Manuscript No: COCR-23-88436;

Editor Assigned: February 03, 2023; PreQC Id: COCR-23-88436 (PQ);

Reviewed: February 13, 2023; QC No: COCR-23-88436 (Q);

Revised: February 15, 2023; Manuscript No: COCR-23-88436 (R);

Published: February 18, 2023; DOI: 10.4172/cocr.6(2).276

Citation: Paredes de la Fuente R, Anderson ME, Peters MLB (2023) Primary Undifferentiated Neoplasm of the Left Arm with Characteristics of Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumor and High-Grade Sarcoma. Clin Oncol Case Rep 6:2

Abstract

A previously healthy man in his late 20s was diagnosed with a primary undifferentiated non- metastatic tumor of the left arm. After a biopsy, a clear pathological diagnosis could not be established. The tumor had positive immunohistological markers for both an extragonadal germ cell tumor and a high-grade sarcoma. Given the presumed germ cell etiology, he was started on empiric chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin. After a few cycles, the tumor showed dramatic response. However, due to poor patient follow- up, it progressed to massive size with severe compromise of the joint and critical neurovascular structures, which led to the decision for limb amputation. Post-surgical checkups showed no recurrence of the primary tumor or metastasis. This is the first report in the literature showing a tumor with these histological characteristics that responded to platinum-based therapy. It provides evidence for the need of more specific markers for the pathological evaluation of undifferentiated neoplasms.

Keywords: Extragonadal germ cell tumor; High-grade sarcoma; Undifferentiated neoplasm; Case report

Introduction

Undifferentiated neoplasms are a heterogenous group of tumors missing a specific differentiation lineage or that have unidentifiable primary origin if based on morphological characteristics alone [1]. These entities are a diagnostic challenge, even with the increasing use of immunohistochemical and biochemical tumor markers. This obstacle is due in part to the large number of possible tumor origins and the lack of specific histological features [2]. Many of these tumors are eventually determined to be carcinomas or sarcomatoid carcinomas [1].

Studies have also demonstrated that given the tumor’s morphology, location of the lesion, and patient’s age, pathologists were able to correctly identify the neoplasm’s tissue of origin in almost half the cases [3].

Germ Cell Tumors (GCTs) may present as undifferentiated neoplasms, particularly extragonadal GCTs, representing between 1.6% to 5.5% of cases [2,4,5]. They are mainly found along the midline with the main sites being the anterior mediastinum, the retroperitoneal, hypophyseal and suprasellar regions, but rarely can appear outside midline structures [4-8].

Another important diagnostic possibility when evaluating undifferentiated neoplasms is soft-tissue sarcoma. In general, these tumors consist of a heterogeneous population of cells with mesenchymal features [9]. These cases present most commonly in the extremities of patients with a peak incidence from 60 years to 70 years of age [10,11]. Clinically they present as deep-seated, progressively enlarging masses with rapid growth that may be associated with local pain [12]. The main problem with the histological diagnostic approach of this tumor type is that cellular staining for markers such as vimentin, alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), CD34, and CD68 is neither sensitive nor specific [13].

Herein we introduce a case that presented a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma: An undifferentiated neoplasm of the left arm that presented with multiple positive stains for highly sensitive and specific GCT markers without evidence of disease elsewhere in the body, and which partially responded to cisplatin-based chemotherapy.

Case Report

A male patient in his late 20s with no previous medical history presented to the orthopedics outpatient clinic. He came in with progressive enlargement of the proximal left arm, pain and limited range of motion characterized by the inability to abduct or forward flex his shoulder greater than 90° mainly due to the mass effect. He stated that the swelling worsened gradually throughout a monthlong period, and only some days prior to the consultation did he start to experience pain. He denied paresthesia or weakness. He had a Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) done because of a pain-related emergency visit prior to the consultation which showed a large heterogeneous soft tissue mass. Physical examination at that time confirmed the symptoms with the only additional finding being decreased sensation to light touch in the axillary nerve distribution.

An ultrasound-guided left shoulder mass biopsy was performed to establish the diagnosis, which showed a neoplasm with intact staining for INI-1 and SMARCA4. The tumor cells were also diffusely positive for OCT3/4, SALL4, AE1/3-CAM 5.2 (patchy) and MNF-116 (focal); negative stains included SMA, desmin, CD99, S100, CD45, AFP, hCG, PLAP, CD30, CDX-2, and glypican-3. Cytogenetics revealed negative FISH studies for isochromosome 12p. The pathological diagnosis was high grade malignant neoplasm after multiple revisions. However, given the cytokeratin positivity which suggested carcinoma and OCT3/4 and SALL4 positive staining a high suspicion for metastatic germ cell tumor was proposed, although a high-grade primitive sarcoma could not be ruled out.

The patient underwent multiple diagnostic studies without significant findings including a testicular US to rule out a primary site. There was also no mediastinal or retroperitoneal involvement and both AFP and hCG were normal. A PET/CT showed an extremely hypermetabolic heterogenous 11.6 cm x 7.0 cm x 8.0 cm mass in the left shoulder deltoid muscle and adjacent to the lateral aspect of the humeral head. Furthermore, extensive hypermetabolic regional axillary lymphadenopathy was present (Figure 1).

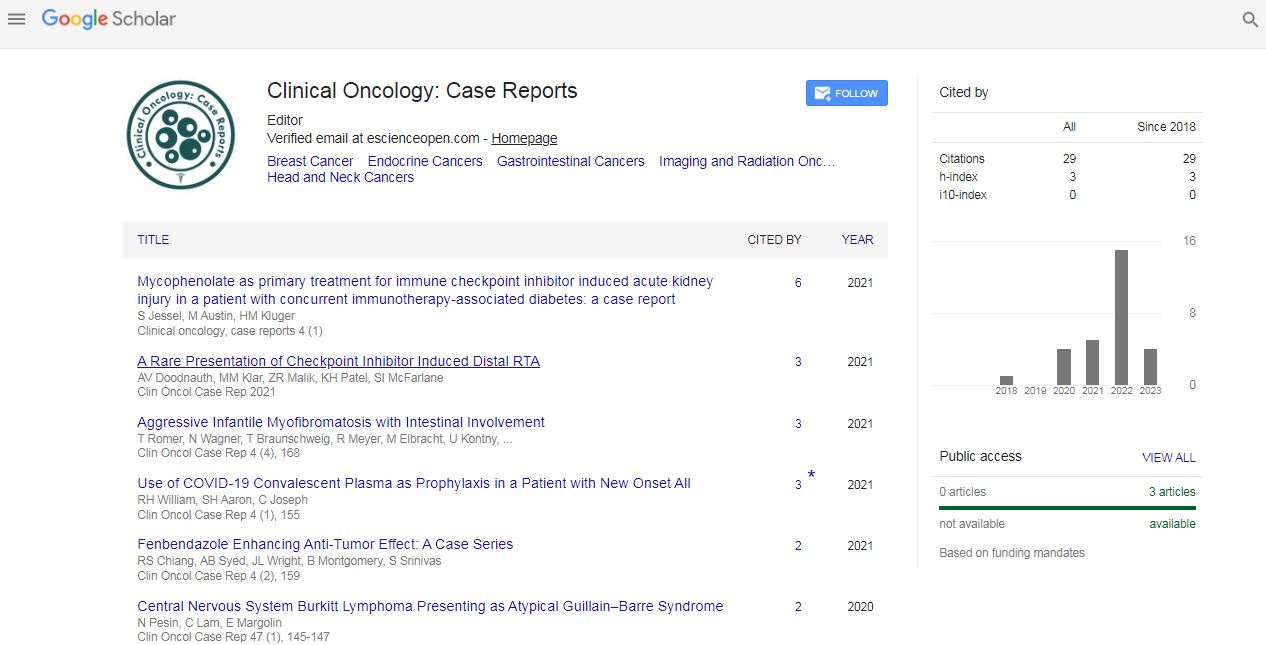

Figure 1: MRI of left arm showing large heterogenous soft tissue mass about the proximal humerus without evidence of bony involvement.

He was started on empiric chemotherapy with etoposide and cisplatin given the presumed germ cell etiology. Due to poor tolerability and follow-up, the patient only completed his first cycle in full. He received another 3 partial cycles and the tumor and axillar nodules responded partially to each incomplete treatment cycle. He then received additional palliative radiotherapy to the left shoulder but was not able to complete the full treatment course. His tumor was also submitted for somatic tumor profiling, which showed microsatellite status stable, a low tumoral mutational burden (4 Muts/Mb) and no reportable genomic alterations. He was lost to follow up for a brief period. Then five months after finishing radiotherapy treatment, he wasseen again. At that time, tumor progression was seen on imaging with a mass that measured 14 cm x 2 cm x 12.2 cm x 17 cm and anterior humeral head dislocation. It was decided to start palliative gemcitabine but the patient missed several treatments. Furthermore, the tumor failed to respond and the mass expanded, significantly affecting the patient with pain and lack of function.

The patient was lost to follow up again for about six months. When he returned to care the patient reported that the mass continued to grow and became extremely painful. He also lost the use of his left arm and was unable to perform some daily functions. On MRI the tumor made up the entirety of his arm starting at the glenohumeral joint as shown in Figure 2. Ultimately, a consensus was made that the patient should undergo a left upper extremity forequarter amputation, axillary node resection and targeted muscle reinnervation at the left brachial plexus level. On pathology review of the resected specimen, the mass was still positive for SALL4 withmorphological resemblance to the patient’s prior biopsy. It was negative for AE1/3-CAM 5.2, CK20, CK7, WT1, ERG, CD68, chromogranin and synaptophysin. The axillary lymph node metastasis showed a poorly differentiated tumor consistent with germ cell neoplasm. Cells were positive for SALL4, OCT3/4 and focal AE1/3-CAM 5.2 and negative for PAX 5. The cellular component from both sites were identical. On further review, considering that the tumor had characteristics indicating that it could be a GCT, but the diagnosis of sarcoma could not be ruled out, a consensus was made that this was an undifferentiated tumor with primitive marker expression without a clear tissue of origin.

Figure 2: MRI showing massive left shoulder/upper arm mass with extensive osseous destruction of the humerus increased in size compared with the prior image with extensive likely metastatic left axillary lymphadenopathy.

After the surgery, he was discharged without complications. However, he has continued to miss follow-up appointments and has only been seen in the immediate post-operative period at which time he reported continued mild pain without additional findings.

Discussion

Our case was diagnosed in the final histological report as an undifferentiated tumor with primitive expression markers. One of the primary methods used to establish germ cell origin of undifferentiated tumors is by identifying isochromosome 12p [2,14,15]. However, even though this is a highly useful diagnostic tool it is not present in all samples and its absence should not be a criteria to discard the possible diagnosis of a GCT [14]. On the other hand, it is important to point out that this tumor was positive for several immunohistochemical markers associated with germ cell tumors. OCT3/4 is considered an important regulator of the pluripotency capabilities and the self-renewal of normal embryonic stem and primordial germ cells (PGCs) [16]. The diagnostic utility of OCT3/4 has been explored in different reports as a marker for GCTs [17,18]. As it stands today, this marker is regarded as an absolute indicator of the presence of in situ/intratubular germ cell neoplasia [18]. The proliferation of the cells within the seminiferous tubules driven by specific Y chromosome encoded proteins coupled with the expression of KIT ligands in Sertoli cells drives them towards tumor genesis [15]. OCT3/4 promotes tumor formation by acting as an oncogene, with some studies even suggesting it as a potential therapeutic target [19]. Additionally, this patient’s tumor had a positive stain for SALL4. This gene encodes proteins that regulate OCT4 working in the maintenance of pluripotency and selfrenewal of embryonic stem cells [20]. Different studies have determined its utility as a stem cell marker for extragonadal germ cell tumors [21-23]. These reports have estimated high sensitivity compared to conventional and novel stem cell markers [21,22]. This includes PLAP, APF, and -CD30, all of which have limited sensitivity and or specificity when dealing with extragonadal GCTs [21]. This high sensitivity is also seen when compared to glypican-3, a novel maker previously used for diagnosing testicular yolk sac tumors (negative in this case) [24]. It has to be taken into consideration that these results reflect samples taken from mostly midline tumors, However, it has been suggested that due to their high sensitivity for germ cell tumors they should become part of the initial work up of undifferenced tumor at any location in patients of any age [1,22]. In addition, even though some studies have postulated that chemotherapy decreases the immunoreactivity of certain markers [25]; these GCT-sensitive markers are reportedly not affected by the use of previous chemotherapy [21,22]. This case would have probably benefited from the use of other highly sensitive GCT markers such as LIN28 or gene expression profiling by detection of either messenger RNA or microRNA as a way to further clarify its lineage [1].

There is still an ongoing discussion as to whether extragonadal GCTs are exclusively found in the midline. From our literature search a similar location for an extranodal GCT has only been reported once [6]. The main hypothesis regarding the formation of extragonadal GCTs states that PGCs originating from the proximal epiblast migrate along the midline of the body, then go through the hindgut to the genital ridge [26, 27]. This allows germ cell precursors to be misplaced through their trajectory. This theory is supported by the presence of extragonadal PGCs in the embryo [28]. PGCs are regarded as the main precursor to GCT due to their resemblance pertaining to their morphological and histological structure [26]. However, this theory would not explain this patient’s tumor location. Another common line of thought is that extragonadal GCT represents a metastatic form of a primary gonadal GCT [29, 30]. This is based on evidence from some histological studies that found fibrous tissue and microlithiasis in the testicles of patients with concomitant GCT, regarded as evidence of a regressed primary lesion [26, 31]. A final theory is the “entrapment theory” postulated by Sano and colleagues [32]. It states that during the formation of the primitive streak PGCs might become entrapped in it or actively migrate with migrating mesodermal cells. Although this theory was first conceived to try to explain the generation of intracranial GCTs, we can see that many of the reported data in regards to extragonadal GCTs’ topographic location have a common mesodermal origin [6, 7, 33, 34].

Finally, the initial therapy for this patient was chosen in accordance per NCCN guidelines for treating occult primary tumors in male patients younger than 40-years [35]. Their recommendation state that physician should be to treat the patient as a poor-risk germ cell tumor per their testicular cancer guidelines. Furthermore, previous reports have found that young patients with mediastinal and retroperitoneal undifferentiated neoplasms have responded to cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy in a way identical to what would be expected from tumors from germ cell origin [2]. As in the cited cases, this tumor also showed a high response to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. If we base in part our diagnosis on the tumor’s therapeutic response, this could be considered an important clue in its assessment and diagnosis. It has been well-documented that testicular GCTs are susceptible to conventional cisplatin-based combination chemotherapy [36]. It has even led to an improvement in the overall survival of the disease with current 5-year relative survival reported as high as 95% [37]. Even though extragonadal GCTs are considered to have a worse prognosis, particularly nonseminomatous GCTs [38], current guidelines still recommend platinum-based combination chemotherapy due to its high level of response [39].

The main differential throughout the case was the possibility that the tumor represented a high-grade soft tissue sarcoma. The main point in favor of this diagnosis was the presence of positive cytokeratin markers. Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcomas have been found to have aberrant expression of cytokeratin which tends to be focal [1]. Another important point is that even though most of the specific markers for this type of tumor came back negative, given the undifferentiated state of the pathological sample this could not be considered sufficient evidence to rule out the diagnosis [13]. Therapy guidelines for soft tissue sarcoma are oriented more towards surgical resection as a mainstay of therapy [13, 40]. The tumor in this case, fortunately, has not shown metastatic potential beyond locoregional lymph nodes and therefore, we believe he has been cured by resection.

Chemotherapy options for high-grade sarcomas are more geared towards metastatic disease, and first line anthracycline-based regimens are regarded as the main therapeutic approach [40]. The most commonly used drugs are ifosfamide and doxorubicin [41]. Another therapeutic option is the use of gemcitabine-based regimen [42]. However, Gronchi and colleagues determined in a recent clinical-trial that disease-free survival was superior in high-risk soft tissue sarcoma subjects receiving standard chemotherapy than those treated with a gemcitabine plus docetaxel regimen (HR 2.17, 95% CI, 0.98 - 4.80) [43], these findings which were later confirmed by a wider, open-label, multicenter randomized clinical trial [42]. Moreover, studies have found difficulties in the treatment of GCTs with sarcomatous components because the latter do not respond to the usual chemotherapeutic regimens [44]. As expected from a normal GCT, our patient responded partially to an incomplete therapy with etoposide and cisplatin which ultimately ended up regressing in part due to the lack of follow-up. He also showed some response with gemcitabine monotherapy which could be consistent with either proposed diagnosis.

Conclusion

Evaluation of undifferentiated neoplasms presents a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge. This case illustrates a tumor that expressed many highly sensitive markers for GCT despite the atypical location, and did show good to cisplatin-based empiric treatment. However, serological markers were normal and sarcoma remained in the differential, perhaps bolstered by the lack of metastatic behavior despite long periods without treatment. This case demonstrates the need for more specific markers for the pathological evaluation of undifferentiated neoplasms.

References

- Lin F, Liu H (2014) Immunohistochemistry in undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med 138: 1583-1610. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Summersgill B, Goker H, Osin P, Huddart R, Horwich A, et al. (1998) Establishing germ cell origin of undifferentiated tumors by identifying gain of 12p material using comparative genomic hybridization analysis of paraffin-embedded samples. Diagn Mol Pathol 7: 260-266. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sheahan K, O’Keane JC, Abramowitz A, Carlson JA, Burke B, et al. (1993) Metastatic adenocarcinoma of an unknown primary site: A comparison of the relative contributions of morphology, minimal essential clinical data and CEA immunostaining status. Am J Clin Pathol 99: 729-735. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Stang A, Trabert B, Wentzensen N, Cook MB, Rusner C, et al. (2012) Gonadal and extragonadal germ cell tumours in the United States, 1973-2007. Intern J Androl 35: 616-625. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Rusner C, Trabert B, Katalinic A, Kieschke J, Emrich K, et al. (2013) Incidence patterns and trends of malignant gonadal and extragonadal germ cell tumors in Germany, 1998–2008. Cancer Epidemiol 37: 370-373. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Benali HA, Lalya lssam, Allaoui M, Benmansour A, Elkhanoussi B, et al. (2012) Extragonadal mixed germ cell tumor of the right arm: Description of the first case in the literature. World J Surg Oncol 10: 1-4. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Kleinhans B, Kalem T, Hendricks D, Arps H, Kaelble T (2001) Extragonadal germ cell tumor of the prostate. J Urol 166: 611-612. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Kumar Y, Bhatia A, Kumar V, Vaiphei K (2007) Intrarenal pure yolk sac tumor: an extremely rare entity. Intern J Surg Pathol 15: 204-206. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Robles-Tenorio A, Solis-Ledesma G (2022) Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publis. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Chen S, Huang W, Luo P, Cai W, Yang L, et al. (2019) Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma: Long-term follow-up from a large institution. Canc Manage Res 11: 10001-10009. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Toro JR, Travis LB, Wu HJ, Zhu K, Fletcher CDM, et al. (2006) Incidence patterns of soft tissue sarcomas, regardless of primary site, in the surveillance, epidemiology and end results program, 1978-2001: An analysis of 26,758 cases. Interna J Can 119: 2922-2930. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Tos AP (2006) Classification of pleomorphic sarcomas: Where are we now? Histopathol 48: 51-62. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Nascimento AF, Raut CP (2008) Diagnosis and management of pleomorphic sarcomas (so-called “MFH”) in adults. J Surg Oncol 97: 330-339. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Houldsworth J, Korkola JE, Bosl GJ, Chaganti RS (2006) Biology and genetics of adult male germ cell tumors. J Clin Oncol 24: 5512-5518. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Pinto MT, Carcano FM, Vieira AG, Cabral ER, Lopes LF (2021) Molecular biology of pediatric and adult male germ cell tumors. Can 13: 2349. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- De Jong J, Looijenga LH (2006) Stem cell marker OCT3/4 in tumor biology and germ cell tumor diagnostics: history and future. Crit Rev Oncog 12. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Rijlaarsdam MA, Van Herk HADM, Gillis AJM, Stoop H, Jenster G, et al. (2011) Specific detection of OCT3/4 isoform A/B/B1 expression in solid (germ cell) tumours and cell lines: Confirmation of OCT3/4 specificity for germ cell tumours. Brit J Can 105: 854-863. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- De Jong J, Stoop H, Dohle GR, Bangma CH, Kliffen M, et al. (2005) Diagnostic value of OCT3/4 for pre‐invasive and invasive testicular germ cell tumours. J Pathol: J Pathol Soc Great Britain Ireland 206: 242-249. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Hu T, Liu S, Breiter DR, Wang F, Tang Y, et al. (2008) Octamer 4 small interfering RNA results in cancer stem cell-like cell apoptosis. Cancer Res 68: 6533-6540. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Zhang J, Tam WL, Tong GQ, Wu Q, Chan H-Y, et al. (2006) SALL4 modulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and early embryonic development by the transcriptional regulation of POU5F1. Nat Cell Biol 8: 1114-1123. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Liu A, Cheng L, Du J, Peng Y, Allan RW, et al. (2010) Diagnostic utility of novel stem cell markers SALL4, Oct4, Nanog, Sox2, UTF1, and TCL1 in primary mediastinal germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 34: 697-706. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Camparo P, Comperat EM (2013) SALL4 is a useful marker in the diagnostic work-up of germ cell tumors in extra-testicular locations. Virchows Archiv 462: 337-341. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Wang F, Liu A, Peng Y, Rakheja D, Wei L, et al. (2009) Diagnostic utility of SALL4 in extragonadal yolk sac tumors: an immunohistochemical study of 59 cases with comparison to placental-like alkaline phosphatase, alpha-fetoprotein, and glypican-3. Am J Surg Pathol 33: 1529-1539. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Zynger DL, Dimov ND, Luan C, Tean Teh B, Yang XJ (2006) Glypican 3: A novel marker in testicular germ cell tumors. Am J Surg Pathol 30: 1570-1575. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Berney DM, Shamash J, Pieroni K, Oliver RT (2001) Loss of CD30 expression in metastatic embryonal carcinoma: The effects of chemotherapy? Histopathol 39: 382-385. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Oosterhuis JW, Stoop H, Honecker F, Looijenga LH (2007) Why human extragonadal germ cell tumours occur in the midline of the body: Old Concepts, new perspectives. Intern J Androl 30: 256-264. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Ronchi A, Cozzolino I, Montella M, Panarese I, Zito Marino F, et al. (2019) Extragonadal germ cell tumors: Not just a matter of location. A review about clinical, molecular and pathological features. Cancer Med 8: 6832-6840. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Ariel-Glenn O, Barkovich J (1996) Intracranial germ cell tumors: A comprehensive review of proposed embryologic derivation. Pediatric Neurosurg 24: 242-251. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- McKenney JK, Heerema-McKenney A, Rouse RV (2007) Extragonadal germ cell tumors: A review with emphasis on pathologic features, clinical prognostic variables, and differential diagnostic considerations. Adv Anat Pathol 14: 69-92. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Yucel M, Kabay S, Saracoglu U, Yalcinkaya S, Hatipoglu NK, et al. (2009) Burned-out testis tumour that metastasized to retroperitoneal lymph nodes: A case report. J Med Case Rep 3: 1-4. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Bokemeyer C, Hartman JT, Fossa SD, Droz JP, Schmol HJ, et al. (2003) Extragonadal germ cell tumors: Relation to testicular neoplasia and management options. J Pathol, MIcrobiol Immunol. 111: 49-63. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Sano K, Matsutani M, Seto T (1989) So-called intracranial germ cell tumours: Personal experiences and a theory of their pathogenesis. Neurolo Res 11: 118-126. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Hanna NH, Ulbright TM, Einhorn LH (2002) Primary choriocarcinoma of the bladder with the detection of isochromosome 12p. J Urol 167: 1781-1782. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Stolnicu S, Szekely E, Molnar C, Molnar CV, Barsan I, et al. (2017) Mature and immature solid teratomas involving uterine corpus, cervix, and ovary. Intern J Gynecol Pathol: Off J Intern Soc Gynecol Pathol 36: 222. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Immunohistochemistry in undifferentiated neoplasm/tumor of uncertain origin

- Singh R, Fazal Z, Freemantle SJ, Spinella MJ (2019) Mechanisms of cisplatin sensitivity and resistance in testicular germ cell tumors. Cancer Drug Resist 2: 580. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- [Google Scholar]

- Chahoud J, Kohli M (2020) Managing extragonadal germ cell tumors in male adults. AME Med J 5: 8. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Gilligan T, Lin DW, Aggarwal R, Chism D, CostN, et al. (2022) Testicular cancer, version 2.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. Nat Compreh Cancer Net Inc 17: 1529-1554. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Mehren MV, Kane JM, Agulnik M, Bui MM, Carr-Ascher J, et al. (2022) Soft tissue sarcoma, version 2.2022, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 20: 815-833. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Palumbo R, Neumaier C, Cosso M, Bertero G, Raffo P, et al (1999) Dose-intensive first-line chemotherapy with epirubicin and continuous infusion ifosfamide in adult patients with advanced soft tissue sarcomas: A phase II study. Europ J Can 35: 66-72. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Gronchi A, Palmerini E, Quagliuolo V, Martin Broto J, Lopez PA, et al. (2020) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in high-risk soft tissue sarcomas: Final results of a randomized trial from Italian (ISG), Spanish (GEIS), French (FSG), and Polish (PSG) sarcoma groups. J Clin Oncol 38: 2178-2186. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Gronchi A, Ferrari S, Quagliuolo V, Broto JM, Pousa AL, et al. (2017) Histotype-tailored neoadjuvant chemotherapy versus standard chemotherapy in patients with high-risk soft-tissue sarcomas (ISG-STS 1001): An international, open-label, randomised, controlled, phase 3, multicentre trial. Lancet Oncol 18: 812-822. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

- Malagon HD, Valdez AMC, Moran CA, Suster S (2007) Germ cell tumors with sarcomatous components: A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 46 cases. Am J Sur Pathol 31: 1356-1362. [Google Scholar] [Cross Ref]

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi