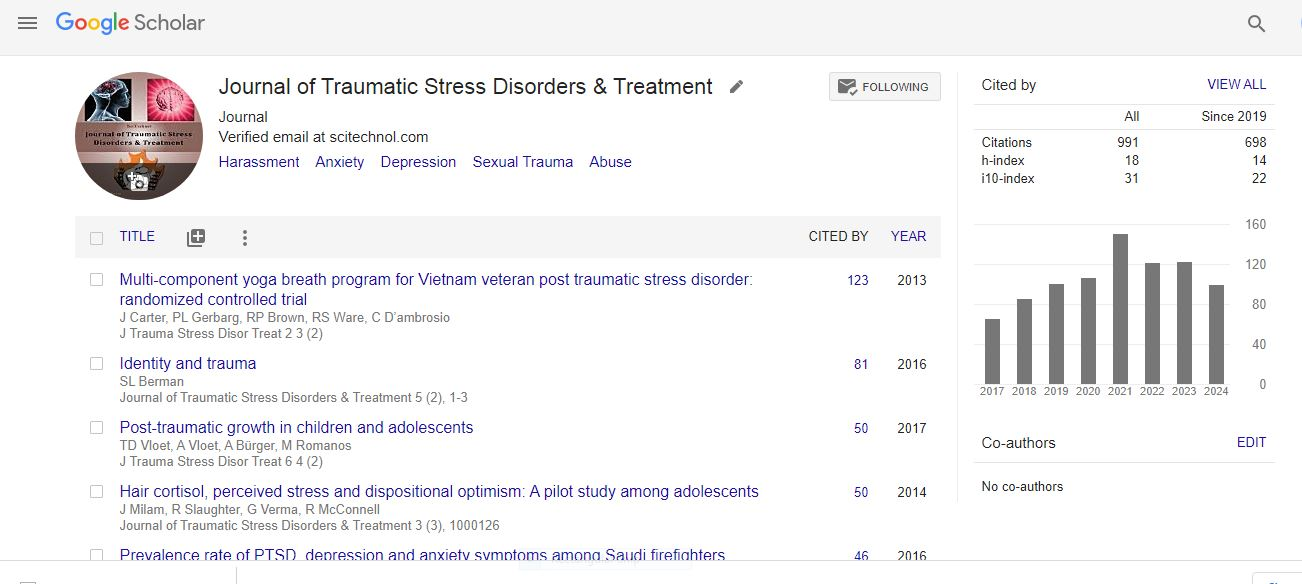

Perspective, Jtsdt Vol: 13 Issue: 6

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and its Neuropsychiatric Sequelae: Chronic Anxiety and Cognitive Decline.

Esther Nambogo*

Department of Mental Health, Makerere University, Uganda

*Corresponding Author: Esther Nambogo

Department of Mental Health, Makerere University, Uganda

E-mail: esther.nambogo@email.com

Received: 30-Nov-2024, Manuscript No. JTSDT-24-153748;

Editor

assigned: 02-Dec-2024, PreQC No. JTSDT-24-153748 (PQ);

Reviewed: 13-Dec-2024, QC No. JTSDT-24-153748;

Revised: 16-

Dec-2024, Manuscript No. JTSDT-24-153748(R);

Published: 22-Dec-

2024, DOI:10.4172/2324-8947.100432

Citation: Nambogo E (2024) Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and its Neuropsychiatric Sequelae: Chronic Anxiety and Cognitive Decline. J Trauma Stress Disor Treat 13(6):432

Copyright: © 2024 Nambogo E. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Introduction

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a severe psychiatric condition that occurs in response to traumatic events, characterized by persistent symptoms of re-experiencing the traumatic event, hyperarousal, and avoidance behaviors. Initially recognized in veterans and survivors of warfare, PTSD has since been acknowledged as a common disorder among individuals who have experienced a wide range of traumatic events, including sexual assault, natural disasters, and accidents. Beyond its psychological distress, PTSD has significant neuropsychiatric sequelae that can profoundly affect an individual’s emotional well-being and cognitive function [1].

While PTSD is often associated with symptoms of anxiety, depression, and hyperarousal, it is also linked to chronic anxiety and cognitive decline. These neuropsychiatric consequences significantly contribute to the burden of the disorder, often impairing the quality of life and functioning of affected individuals. This article explores the neuropsychiatric sequelae of PTSD, focusing on chronic anxiety and cognitive decline, and discusses the mechanisms, clinical manifestations, and potential treatment strategies [2].

Anxiety is one of the hallmark symptoms of PTSD, affecting a significant portion of those diagnosed with the disorder. It manifests in several ways, including generalized anxiety, panic attacks, and specific phobias. Individuals with PTSD are often hypervigilant, constantly on edge, and prone to anxiety-provoking thoughts or flashbacks related to the traumatic experience. The neurobiological mechanisms underlying chronic anxiety in PTSD are complex and involve multiple brain regions responsible for fear processing, emotional regulation, and memory [3].

The amygdala, which plays a critical role in processing fear and emotional responses, is often hyperactive in individuals with PTSD. In contrast, the prefrontal cortex (PFC), responsible for regulating emotions and inhibiting inappropriate responses, may be underactive. This imbalance between the amygdala and PFC leads to heightened emotional reactivity and reduced ability to control fear responses. Additionally, the hippocampus, a brain region essential for memory consolidation, is often structurally altered in individuals with PTSD. Decreased hippocampal volume has been linked to difficulties in distinguishing between past and present experiences, which can contribute to the re-experiencing of traumatic memories and increased anxiety [4].

The chronic anxiety associated with PTSD leads to significant impairment in daily functioning. Individuals may avoid situations or places that remind them of the traumatic event, which can result in social isolation and difficulty maintaining relationships. Sleep disturbances, such as insomnia and nightmares, further exacerbate anxiety symptoms, contributing to a vicious cycle that makes recovery challenging [5].

Treatment for chronic anxiety in PTSD involves a combination of pharmacological and psychological interventions. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as sertraline and paroxetine, are commonly prescribed to reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), particularly Trauma-Focused CBT (TF-CBT), is considered the gold standard in psychotherapy for PTSD. TF-CBT helps individuals confront and process traumatic memories in a safe environment while teaching coping strategies to manage anxiety [6].

In some cases, medications like benzodiazepines or alpha-1 blockers (e.g., prazosin) may be used for short-term relief, but these are generally avoided for long-term management due to the risk of dependence or exacerbating cognitive deficits. Cognitive decline is another significant neuropsychiatric sequela of PTSD that can manifest as impairments in memory, attention, executive function, and processing speed. Many individuals with PTSD report difficulties in concentrating, learning new information, and organizing thoughts. Cognitive dysfunction is particularly prevalent in individuals with chronic PTSD or those who have experienced multiple traumatic events [7].

The underlying mechanisms of cognitive decline in PTSD are believed to involve disruptions in the brain regions responsible for memory and executive function. Chronic stress, which is a hallmark of PTSD, can lead to elevated levels of cortisol, a stress hormone that, in excess, can negatively affect brain structures such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Prolonged exposure to high cortisol levels can impair neurogenesis (the formation of new neurons) and reduce the volume of the hippocampus, contributing to memory deficits and cognitive dysfunction [8].

Furthermore, PTSD has been associated with alterations in neurotransmitter systems, including the dysregulation of serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate, all of which play critical roles in cognitive processes. These neurochemical imbalances can further impair cognitive function, particularly in tasks requiring attention, concentration, and decision-making. Cognitive deficits in PTSD can significantly impair an individual’s ability to function in everyday life. Memory difficulties can hinder work performance, academic achievement, and social interactions. Impaired executive function may make it challenging to plan, prioritize, and execute tasks [9].

Addressing cognitive decline in PTSD requires a multifaceted approach. Pharmacological treatments targeting specific cognitive symptoms may help, though evidence for their efficacy is still emerging. Medications such as modafinil, which enhance cognitive function, or other cognitive enhancers, may be considered, particularly for individuals with significant impairments in attention and processing speed. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) is a promising approach that involves structured training to improve cognitive skills such as memory, attention, and problem-solving. CRT can be delivered through computerized programs or in-person sessions and is designed to help individuals regain lost cognitive abilities [10].

Conclusion

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating disorder with significant neuropsychiatric sequelae. Chronic anxiety and cognitive decline are among the most prominent and disabling consequences of PTSD, affecting individuals across all areas of life. The mechanisms underlying these sequelae involve alterations in key brain regions, such as the amygdala, hippocampus, and prefrontal cortex, as well as neurochemical imbalances resulting from prolonged stress.

References

- Bremner JD, Pearce B (2016) Neurotransmitter, neurohormonal, and neuropeptidal function in stress and PTSD. PTSD. 179-232.

- Vasterling JJ, Brailey K. Neuropsychological findings in adults with PTSD.

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR (2005) Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62(6):593-602.

- Ehlers A, Ehring T, Wittekind CE, Kleim B (2022) 15 Information Processing in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. 367.

- Pitman RK, Rasmusson AM, Koenen KC, Shin LM, Orr SP (2012) Biological studies of post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat Rev Neurosci. 13(11):769-87.

- Liberzon I, Martis B (2006) Neuroimaging studies of emotional responses in PTSD. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1071(1):87-109.

- Cohen BE, Neylan TC, Yaffe K, Samuelson KW, Li Y (2013) Posttraumatic stress disorder and cognitive function: findings from the mind your heart study. J Clin Psychiatry. 74(11):14869.

- Navarrete F, García-Gutiérrez MS, Jurado-Barba R, Rubio G, Gasparyan A (2020 ) Endocannabinoid system components as potential biomarkers in psychiatry. Front Psych. 11:315.

- Harm M, Hope M, Household A. American Psychiatric Association, 2013, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn, Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 347:64.

- Horner MD, Hamner MB (2002) Neurocognitive functioning in posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychol Rev. 12:15-30.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi