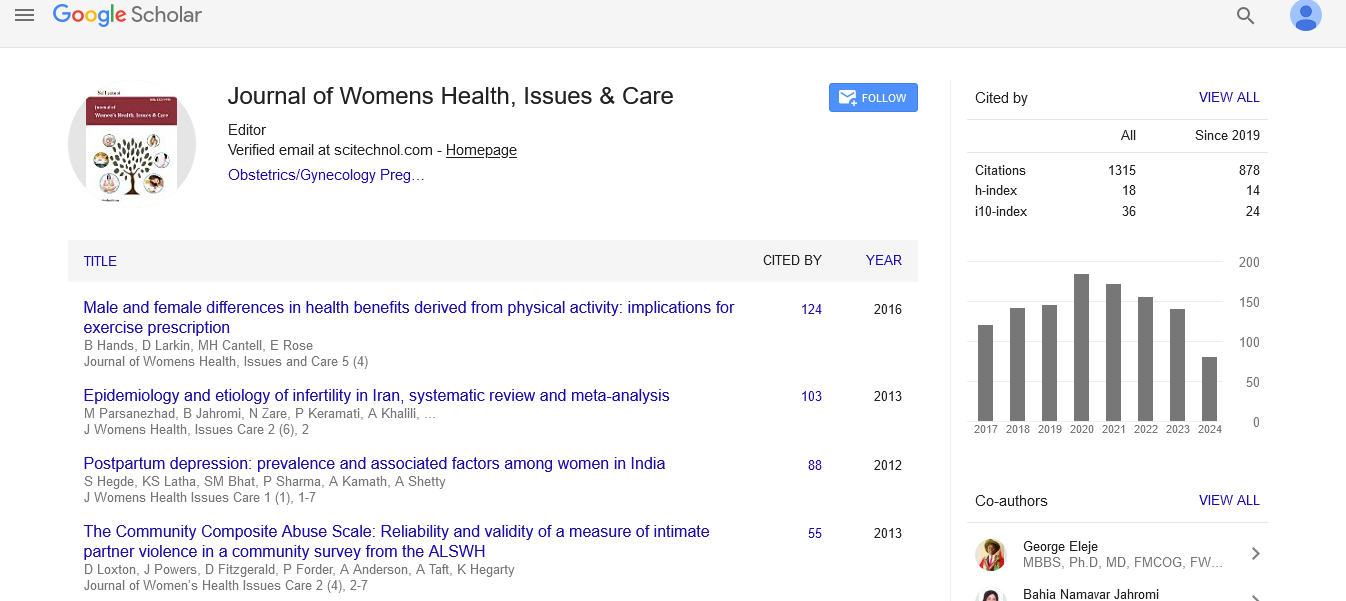

Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 3 Issue: 3

Postnatal Sense of Security, Anxiety and Risk for Postnatal Depression

| Eva K. Persson1* and Linda J. Kvist1,2 | |

| 1Health Sciences Centre, Lund University, Sweden | |

| 2Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Helsingborg Hospital, Sweden | |

| Corresponding author : Eva K. Persson Health Sciences Centre, Lund University, PO Box 157, S-221 00 Lund, Sweden Tel: +46 46 222 1890; Fax: +46 46 2221808 E-mail: eva-kristina.persson@med.lu.se |

|

| Received: February 04, 2014 Accepted: May 16, 2014 Published: May 19, 2014 | |

| Citation: Persson EK, Kvist LJ (2014) Postnatal Sense of Security, Anxiety and Risk for Postnatal Depression. J Womens Health, Issues Care 3:3. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000141 |

Abstract

Postnatal Sense of Security, Anxiety and Risk for Postnatal Depression

Approximately 10%-15% of mothers and 10% of fathers suffer from depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Both maternal and paternal postnatal depression impact adversely on the family and the child’s behavioural development.

Keywords: Anxiety; EPDS; PPSS; Postnatal depression; Preparation for parenthood; Sense of security; STAI-state

Keywords |

|

| Anxiety; EPDS; PPSS; Postnatal depression; Preparation for parenthood; Sense of security; STAI-state | |

Background |

|

| Researchers have reported that approximately 10% - 15% of mothers suffer from depressive symptoms during pregnancy and the postpartum period [1,2] and a recent meta-analysis has shown that about 10% of fathers also suffer from these symptoms [3]. Both maternal and paternal postnatal depression may impact adversely on outcomes for the child, for example psychiatric disorders and the child’s behavioural development [4,5]. Infant temperament may be negatively affected and the child’s biological response to stress may also be compromised [4,5]. It has been demonstrated that states of anxiety and depression are closely related [6,7] and that more research is needed [8]. Tammentie, et al. [9] showed that in postnatally depressed mothers, there was a discrepancy between their expectations of early parenthood and the reality they experienced. It is possible that this discrepancy might be linked to risk for postnatal depression. Parents, especially mothers, wanted the experience of parenthood to be perfect and had high expectations of their life as a family. Despite these expectations, there was a sense that the infant tied them down. Tammentie et al pointed out the need for support in the postpartum period as an emergent theme in their analysis [9]. | |

| Demands and expectations, from both parents, concerning fathers’ participation during childbirth, responsibility for the child and equal participation in family life, have increased, in recent years, especially in high-income countries [10-13]. It has been shown that increased involvement of fathers in maternity care, both pre- and postnatally, increases mothers’, fathers’ and children’s wellbeing and may be protective in maternal and paternal depression [14,15]. Persson, et al. [16,17] have shown that fathers’ participation from early pregnancy and parents’ antenatal preparation for the early postnatal period are important factors for postnatal sense of security for both parents. | |

| The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) [1] is a widely used and validated instrument for the measurement of risk for postnatal depression, which was originally developed for use in women, but is in some studies used also for fathers [18,19]. The scale measures both anxiety and depression and is commonly used at approximately two to three months postpartum. Recently Massoudi, et al. [20] showed that that the EPDS scale picked up more worry, anxiety and unhappiness than depression when used for fathers. The STAI-state (State Trait Anxiety Inventory) instrument was developed to measure present anxiety [21]. However, this instrument is not a specific instrument for the postnatal period but may be used for evaluating anxiety in any specific situation [22]. | |

| Feelings of security in the early postnatal period are important for parents and for the wellbeing of the infant [16,17,23]. Earlier research has identified factors important for parents’ postnatal sense of security and the instrument Parents’ Postnatal Sense of Security (PPSS) has been developed to measure these factors [23]. Factor analysis identified four dimensions of importance for security during the first week after childbirth, for both parents. Three of the dimensions were common to mothers and fathers; a sense of the midwives’/nurses’ empowering behaviour, a sense of affinity within the family and a sense of general well being. For the mothers, the fourth dimension was a sense that breast-feeding was manageable and for the fathers the fourth dimension was a sense of the mother’s well being which included breast-feeding [23]. | |

| We hypothesise that a lack of security in the early postnatal period may be a contributing factor to anxiety and depressive illness. Thus, if correlations exist between the PPSS, EPDS and STAI-state, it may be possible to identify parents at risk for anxiety and depression in an earlier phase. This could help health care providers to form the provision of individually tailored postnatal care in order to reduce the risk for depressive illness. Early identification and treatment of parental depressive symptoms may improve infant outcomes. | |

| The aims of this paper were to determine the levels of correlation between scores on the PPSS, the EPDS and the STAI-state instruments and to test concurrent validity between the EPDS and STAI-state instruments. | |

Materials and Methods |

|

| This paper represents an analysis of material that was collected in a previous study [23]. Questionnaires were sent to mothers and fathers separately, approximately ten weeks postpartum. | |

| Participants and setting | |

| Mothers and fathers (n=160 + 160) to every fifth child born live at term (≥37 weeks) at five hospitals in southern Sweden were sent a letter of invitation to participate in the study by answering questionnaires. After two reminders, 113 (71%) of the mothers and 99 (63%) of the fathers returned the questionnaires. The mean age for mothers was 29.8 years (17-40) and for fathers 32.4 years (21- 52). Most of the parents were cohabitating (106 of the mothers and 94 of the fathers). For 52 (46%) of the mothers and 48 (49%) of the fathers it was their first child. Ninety-nine (88%) of the mothers had experienced a normal vaginal birth and 89 (91%) of the fathers answered that their partner had had a normal vaginal birth. All deliveries were singleton. Twelve (11%) of the mothers and 7 (7%) of the fathers had basic school education (9 years), 53 (47%) of the mothers and 58 (59%) of the fathers had high-school education (12 years) and 44 (39%) of the mothers and 31 (31%) of the fathers had a university/college education. Of the mothers 92 (81%) and of the fathers 81 (82%) were born in Sweden. | |

| Procedures and measurements | |

| The questionnaire included socio-demographic variables, the EPDS instrument [1], STAI – state instrument [18] and the PPSS instrument [23]. | |

| The EPDS instrument consists of 10 items in the form of statements on four point Likert-scales (0-3) to which the parents are asked if they agree. Possible scores are between 0-30. A higher score denotes a higher risk for postnatal depression. | |

| The STAI-state instrument is well validated and consists of 20 items measured on four point Likert scales (1-4). Possible scores are between 20 and 80. A higher score denotes a higher level of anxiety. | |

| The PPSS instrument exists in two similar versions, one for mothers (Cronbach´s alpha coefficient 0.88) and one for fathers (Cronbach´s alpha coefficient 0.77) [23]. The items are statements on four point Likert-scales to which the parents are asked if they agree or not, (1- strongly disagree and 4 – strongly agree). The mother’s version of the PPSS instrument consists of 18 items (possible score 18-72) and the father’s version of 13 items (possible score 13-52). A higher score denotes a higher sense of security. | |

| Both the EPDS instrument and the STAI- state instrument measured, in this study, the situation approximately ten weeks after childbirth. Parents were also asked to re-call the first postnatal week and to answer items on the PPSS instrument. Their answers were used to estimate the correlation between PPSS the first postnatal week with risk for depression and anxiety at approximately 10 weeks after birth. | |

| Statistics | |

| Spearman’s correlation coefficient (rho) was used to examine relationships between the PPSS, the EPDS and the STAI - state instruments. This correlation test was also used to test concurrent validity between the EPDS and the STAI-state instruments. Correlation coefficients of 0.1-0.3 were considered to indicate weak relationship, 0.3-0.5 a moderate relationship and >0.5 a strong relationship [24]. Concurrent validity measures how well an instrument correlates with another established instrument within the same area. | |

| Ethical considerations | |

| The project was implemented in compliance with the ethical principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The material that this paper is based on is taken from an earlier published study [23] which was granted permission by the Research Ethics Committee at (LU235- 03) University, (LU235-03). The letter of invitation contained details of the study, explained that participation was completely voluntary and refusal to join the study would in no way effect present or future care. Informed consent was assumed if parents returned a completed questionnaire. | |

Results |

|

| Correlations between PPSS, EPDS and STAI – state instruments Statistically significant | |

| Statistically significant correlations were shown between scores for postnatal sense of security one week after childbirth, anxiety and the risk for postnatal depression after childbirth for both mothers and fathers; lower scores for security correlate with increased risk for anxiety and depression (Table 1). | |

| Table 1: Correlations (rho) between the PPSS-instrument measuring postnatal sense of security one week after childbirth, the EPDS instrument measuring risk for postnatal depression and the STAI-state instrument, measuring present anxiety, approximately ten weeks after childbirth for mothers and fathers. Spearman´s correlation test (2-tailed). | |

| Concurrent validity between EPDS and STAI state | |

| Results of the analysis of concurrent validity showed high levels of correlation between the EPDS and STAI-state instruments for both mothers and fathers; higher levels of anxiety correlate with an increased risk for depression (Table 2). | |

| Table 2: Concurrent validity between mothers and fathers EPDS scores and STAI-state scores. Spearman’s correlation test (2-tailed). | |

Discussion |

|

| The results from the present study show moderate to strong correlations between the PPSS, EPDS and STAI – state instruments for both mothers and fathers. Correlations between PPSS and EPDS and also between PPSS and STAI-state for mothers were strong, whereas for fathers the correlation between PPSS and EPDS was weak. However, fathers’ scores for PPSS and STAI- state were moderately well correlated which is a finding in line with findings from Massoudi, et al. [20]. This suggests that our hypothesis that a lack of security in the early postnatal period might predispose parents to anxiety and postnatal depression and that anxiety and depression can be seen as indicators of insecurity. The fact that there was a strong concurrent validity between measurements of anxiety and depression indicates that a care environment aimed at reducing anxiety might also help reduce the occurrence of postnatal depression, which can be a serious problem for new families. This probably also indicates that anxiety increases when a person does not feel secure, which is not surprising. A limitation to this study is the risk for recall bias when asking parents to fill in the PPSS instrument 10 weeks after the event. Ideally, the PPSS instrument should be administered within two weeks from the birth. However, it has been demonstrated that women’s memories of childbirth are generally accurate [25]. | |

| Earlier research has indicated areas of particular importance for mothers’ and fathers’ feelings of security in the immediate postnatal period; being well prepared for the time after birth, fathers’ participation from early pregnancy and throughout the childbirth period, knowing who to turn to for advice, being met as an individual and having a planned follow-up before discharge [16,17]. The quality of antenatal preparation for parenthood in Sweden has been discussed [26] but little change has ensued since these discussions. Care providers must focus on giving a realistic picture of life with a small infant in order to reduce the discrepency between expectations and reality felt by many parents [9]. It is possible that friends, relatives and care providers, in an effort to not disrupt pre-birth bonding, avoid discussion of the difficulties of early parenthood. This may be a misguided approach. | |

| If we can increase parents’ postnatal sense of security by helping them to be prepared we may decrease the frequency of anxiety and postnatal depression and in that way improve the well-being of the child. Research has focused on the effects of preparation for childbirth but little is known regarding parents’ views concerning their needs for preparation for parenthood. It is therefore essential to investigate, using qualitative research methods, preparation needs as expressed by parents. By also focusing on both paternal and maternal perspectives, the father’s position can be consolidated, gender equality can increase and the family unit can be strengthened. It has been shown that an involved father has positive effects on the attachment to his child [27]. | |

| Conclusions, implications and further research | |

| A correlation between parents’ postnatal sense of security and risk for postnatal depression was indicated in this study. Further research will address the limitations of the present study so that data is collected prospectively and the PPSS instrument is administered in the early postpartum. This research should also include measurement of EPDS and STAI during the antenatal period in order to provide baseline values. At present, in some areas of Sweden, mothers are screened at two months post-partum using the EPDS. Routine measurement of PPSS after one postpartum week may help to give an early indication of those at risk for postpartum distress. An increased understanding of both parents’ preparation needs for the first weeks after childbirth is essential and should be investigated. | |

Acknowledgements |

|

| The authors wish to thank all parents who made this study possible. This research project was funded by Faculty of Medicine, (Lund University). | |

Disclosure of Interest |

|

| We have no interests to disclose. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi