Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 3 Issue: 3

Mixed Methods Approach to Program Evaluation: Measuring Impact of a Cancer Support Program

| Cindy Gotz1, Savitri W Singh-Carlson2* | |

| 1Todd Cancer Institute, Long Beach Memorial, USA | |

| 2California State University, Long Beach, School of Nursing, USA | |

| Corresponding author : Savitri W. Singh-Carlson, PhD RN, APHN, California State University Long Beach, School of Nursing, Long Beach, California, USA Tel: (562)9854476 E-mail: savitri.singh-carlson@csulb.edu |

|

| Received: March 24, 2014 Accepted: June 06, 2014 Published: June 11, 2014 | |

| Citation: Gotz C, Carlson SWS (2014) Mixed Methods Approach to Program Evaluation: Measuring Impact of a Cancer Support Program. J Womens Health, Issues Care 3:3. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000151 |

Abstract

Mixed Methods Approach to Program Evaluation: Measuring Impact of a Cancer Support Program

Effective program evaluation can lead to understanding impact a program has on the target population it serves. It is important for programs to determine the answer to the question “Did you accomplish what you set out to do?” A mixed methods approach utilizing focus groups, content analysis and development of a quantitative survey instrument was examined.

Introduction |

|

| There are more than 13 million cancer survivors currently living in the United States, with women cancer survivors of breast and uterine cancer being the most common [1]. Studies have provided information related to the side-effects of cancer treatment and its effect on quality of life (QoL) during treatment [2-5]. QoL crosses various domains and affects the ability to function socially, physically, and psychologically for cancer survivors [5-7]. The psychological impact of a cancer diagnosis can take many forms such as; depression, anxiety, fear, and cognitive defects [7]. Because of these psychological factors it is important to treat the whole patient and not just the disease, since health and survivorship are important aspects of health and well-being. Effectively addressing psychosocial impacts of cancer has the opportunity for patients to lead a better quality of life [7]. In response to this need, peer-mentor programs were developed to guide women with breast and gynecologic cancer at an urban Southern California community cancer center. The program was designed to train cancer survivors to take the role of being a peer-mentor. While the mentor programs at this cancer center have been serving breast cancer patients for nearly 15 years and gynecologic cancer for 6 years, program evaluation had not been conducted. Therefore in order to determine the program’s effectiveness from the patients’ and mentors’ perspectives or the patients’ QoL, [8] process evaluation tool was used to measure efficacy of the programs. The evaluation question was developed as: Was the training of the cancer survivors to be mentors and the matching to patients an effective service? | |

| In this paper we will discuss a mixed methods approach and process used to evaluate the peer mentor program at an urban community cancer center. Results of this evaluation were intended to determine if there were any changes needed to be integrated into the existing program or future education sessions for both peer mentors and patients. These efforts could increase effectiveness in peermentor’s approach with patients; thereby resulting in a supportive relationship, which would lead to an enhanced quality of life for both mentors and patients. | |

| In order to determine the effectiveness of a program, it is important to have clear goals and measurable objectives [8]. Along with these goals and objectives is the need to evaluate the program by asking: Did you accomplish what you set out to do? In order to respond to these objectives and goals, process evaluation was used to assess program satisfaction as well as program implementation [8]. In order to conduct an in-depth evaluation of the program, a survey was developed using a mixed methods approach (Appendix A). | |

Materials and Methods |

|

| Institutional Review Board approval was received from the hospital where the mentor program is conducted as well as the university. A qualitative integrative approach, utilizing focus group semi-structured interviews was conducted initially in order to develop surveys that would be delivered to the remainder of the population [9]. In order to reduce bias from a self-select sample method for the focus group, invitations were distributed to the larger population in order to increase generalizability [10]. Weathers, et al., contend these strategies reduce limitations inherent in study methods. An examination of the differences between gynecologic and breast cancer experiences of peer mentors were analyzed in order to identify themes that were used for the development of surveys. | |

| In order to collect inductive data that would provide an in-depth meaning to participants’ perceptions of the peer mentor program, this qualitative approach was a best fit for informing survey development [9]. Content analysis from 2 focus group interviews (1 gynecologic, 1 breast) totaling (N=14) was used to examine themes and commonly reported characteristics. | |

| The quantitative survey was developed for both an online and hard copy format (Appendix A). The hard copy surveys were mailed through the U.S. Postal Service with self-addressed return envelopes. SurveyMonkeyTM, an online program, was used for online survey allowing participants a choice of mailing a completed hard copy survey or completing online. Participants’ demographic data e.g., age, education, length of time in the program, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status (SES) was also gathered. Surveys were anonymous and devoid of any personal identification. Informed consent forms were mailed with hard copies, whereas participants who chose to complete the online survey were advised that continuing with the online survey would be consenting to participation in the study. This ensured anonymity and confidentiality were maintained. Participants were given the option of not continuing with the study at any time during the study without any penalty | |

| Results analyzed from surveys were compared to the qualitative data and other existing evidence on peer counseling for breast and gynecologic cancer patients to confirm the adequacy of this program [11-13]. | |

Results |

|

| Qualitative methods | |

| A total of fourteen (N=14) participants from the two focus groups, were breast cancer mentors (n=10) and gynecologic cancer mentors (n=4). Content and thematic analysis helped to clarify key phrases. A constant comparison of the incoming data provided recurrent themes and clarified key characteristics of participants’ perceptions. Qualitative results were used to develop a 24 item question survey that was instrumental in eliciting data and reflecting mentors’ experiences. Table 1 includes a list of the qualitative semi-structured questions. | |

| Table 1: Semi-structured Focus Group Questions. | |

| Content analysis of the 2 focus groups resulted in four major themes with 15 sub-themes. The major themes were: a) experience of being in a peer mentor relationship; b) communication; c) emotional support/relationships; and d) mentor program value. Themes were consistent between the two groups; however themes differed in relation to: recurrence; experience of being a mentor; and perceived availability of resources. Differences in perceptions between the breast cancer and gynecologic cancer groups may be explained by the nature of gynecologic disease process. Evidence indicates there is a higher rate of recurrence, especially for ovarian cancer [14] and less availability of dedicated resources for gynecologic cancer when compared to breast cancer [13]. | |

| Quantitative methods | |

| The 24 item survey questions were divided into 5 groups as follows: experience, communication, emotional support/ relationships, and mentor program value (Appendix A). Questions were scored on a 5-point Likert scale (1= low value and 5=high value). Although SurveyMonkeyTM was a successful online instrument for collecting responses, a number of participants who were without an email address were sent hard copies of the survey and mailed in their responses. SurveyMonkeyTM allowed for a hardcopy version of the online instrument to be printed (Table 2). Additionally, SurveyMonkeyTM provides a facility for entering the hard copy responses into the same database as the online surveys, allowing for complete data analysis of the entire sample. Using Microsoft Excel version 2003 and SurveyMonkeyTM, descriptive statistics were conducted | |

| Table 2: Quantitative Online Survey Instrument Sections. | |

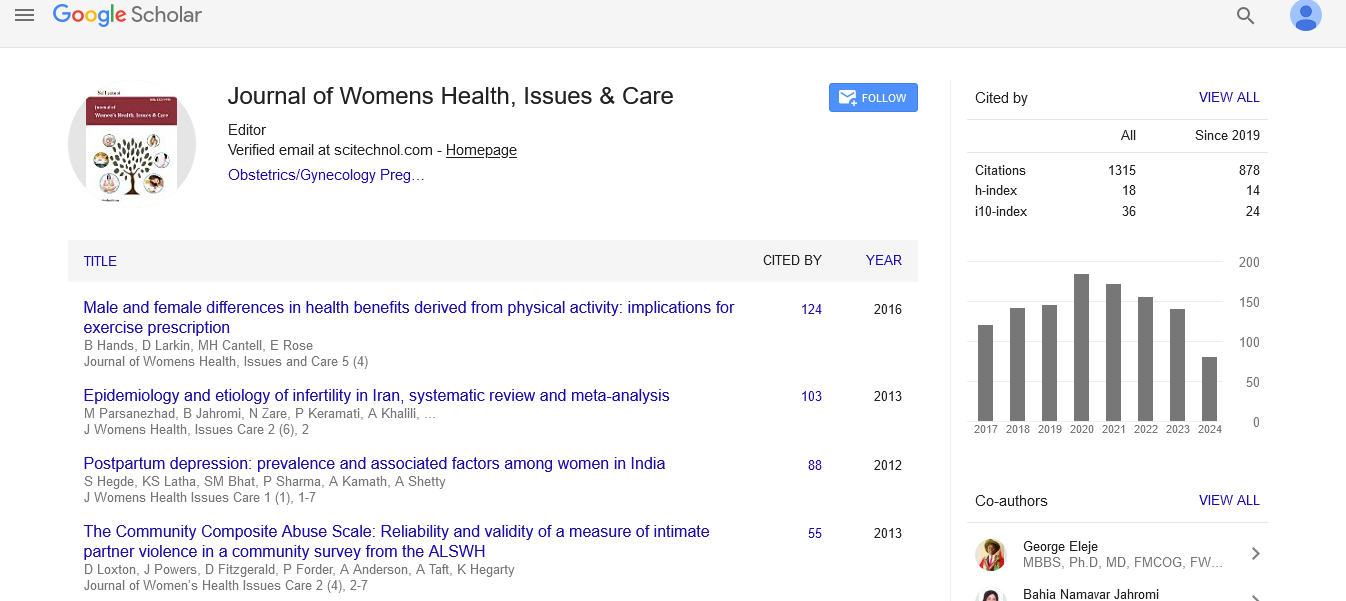

| Participants invited to participate in this program evaluation (N=250) were mentors or patients involved in the peer mentor program at a large urban community cancer center. Surveys consisted of a combination of online (200) and hardcopy (50) surveys (reflected in Figure 1). There was a 28% (n=70) response rate to the surveys. The survey consisted of a 5 point Likert scale with scores of 1 reflecting low satisfaction or value and 5 reflecting high satisfaction value (Appendix A). Table 3 provides the demographic data. | |

| Figure 1: PAI-1 is expressed in response to injury to the carotid artery. | |

| Table 3: Demographics of Survey Respondents. | |

| The health status was reported as good to excellent (Table 4) and nearly all respondents had some level of college education. The majority of respondents were in two age categories (at time of diagnosis) 45 – 54 and 56 – 64 (Table 5). The race distribution was predominately white, a limitation of the study and an area of further development related to program outreach. Overall, the program was rated above average (average= 3 on 5 point scale). Table 5 provides data by category and the mean score for each of the survey categories. | |

| Table 4: Health Status of Survey Respondents. | |

| Table 5: Overall Program Rating. | |

| Results indicated strengths in the area of being a part of a peer mentor relationship. When reviewing each category’s individual questions, themes became apparent. Questions related to the role of the mentor, which was to understand the ‘other cancer survivor’s experiences’ showed an overall mean score of 4.68 and the question “the mentor program representing a sign of hope that cancer is not a death sentence”, had an overall mean score of 4.63. These two were the highest scoring questions overall. Further analysis resulted with mean scores of less than 4 which are presented in Table 6. | |

| Table 6: Questions Receiving mean score <4. | |

| Results showed weaknesses in the area of communication, specifically related to the development of self-advocacy skills and assisting the mentee with decision making. These two elements go hand in hand toward empowering patients to reach their decisionmaking skills with confidence. | |

| The experience of participating in the peer mentor program, when stratified by age group, provided further information related to how a peer mentor relationship impacted the participants’ life. Table 7 details the mean scores for each of the survey domains, value of peer mentor relationship, communication, emotional support and the overall value of the mentor program. The younger age group, 25 to 34 (n=5), indicated a lower mean score related to all aspects of peer support experienced by these women with their assigned peer mentor as compared to other age groups. | |

| Table 7: Mean Responses by Age Group. | |

| The experience of the 35-44 (n=14), 45-54 (n=23) and 55-64 (n=19) age groups reported a higher value with all aspects of the peer mentor experience except communication. Communication was an area of lower scores for all age groups. There were 3 participants who declined to state their age at diagnosis. Closer evaluation of the data indicates the main communication skills and the self-advocacy skills, which are expected to be supported and encouraged by the mentor with the patient, scored low in all age groups. Also, the expectation by the patient to have a safe place to be angry when speaking with a mentor scored low. The 65 and older age group (n=6) reported slightly less value for most of the areas, except how they valued a peer mentor. This age group gave high marks for the role of the mentor in understanding what the other is experiencing. Stage of life and age of the peer mentor assigned to the mentee seem to be important factor in relating to the experience and providing support. | |

Discussion |

|

| The qualitative methodology process for developing the survey instrument using focus groups provided rich qualitative data in designing the instrument that was understood and meaningful for all participants. Using a continuous feedback loop as depicted in Figure 2, the on-going program evaluation can continue to inform changes to the training curriculum ultimately benefiting the program, the patients and the mentors. Program effectiveness should be measured in all sections in order to identify areas of the program that need changes for future sustainability of the peer mentor program [8]. As a result of this evaluation the following changes were made to the peer mentor training curriculum; understanding mentor role boundaries, recognizing where the patient is emotionally, communication expectations and procedures for on-going follow-up with both the mentor and mentee by program staff to see how the match worked. | |

| Figure 2: Constant Feedback Loop. | |

| The continuous feedback loop is a public health model that focuses on the entire populations’ health [15]. There are four main stages of the public health model; defining the problem, identifying risk factors (or protective factors), develops and test an intervention and plan widespread adoption [16]. Considering this program evaluation within this context allows for a step-wise and holistic approach to the needs of cancer survivors. The first three steps of the model were addressed by the evaluation and the final step, planning widespread adoption which will be part of the on-going work program will make a meaningful difference to cancer survivors. Our study results indicated there was some additional work to do in order to provide a program with greater impact, specifically in the area of communication. | |

| The need for continuous and consistent program evaluation is evidenced in our study. Without evaluation there is the danger of repeating the same curriculum for training with the probability of making the peer mentor programs ineffective. Certainly the outcomes within a program are an important component to determining success, but the process evaluation is equally as important as this is the key to determining whether the outcomes are sustainable or why the intervention may have failed [8]. Our findings indicated that age of diagnosis and the stage of life influence the need for information and expectations for developing a relationship with a mentor. These elements make an impact on how peer mentor programs are received by cancer survivors. Program managers need to consider that not everyone will have the same needs and to be open to tailoring the intervention accordingly. Frequently in health care, a great deal of emphasis is placed on the outcomes to determine whether the interventions or programs put in place were successful. Through planned evaluations, one can gain valuable information on how to structure or modify a program in order to achieve the highest impact and most desirable outcomes [17]. | |

| Findings in this study centered on how women differ in their support needs at different ages and/or life stages, for example women in the middle age ranges, 35 to 64, indicated more value in the mentoring relationship than the youngest age group or the eldest age group. It should not be assumed all women diagnosed with cancer will have the same needs and expectations. It is important that programs remain flexible in order to address individual needs of the cancer survivors being mentored. Knowles’ principals of adult learning theory suggest that a teacher is responsible to communicate the importance of what is being taught in a way that learners can see the value and be driven to incorporate the learning into their daily lives [18]. This is an important principal to adopt in the development of a peer mentor program that is going to be targeted at different age groups, education levels, social and cultural factors. | |

Limitations |

|

| Some of the limitations of the study included small sample sizes (focus group n=14 and survey n=70) that were predominately white and educated which may make the findings not be generalizable to other programs or populations. Another limitation was the response rate from the cancer survivors which may point to recruitment strategies utilized in this study. There was a 28% (n=70) response rate to the surveys, while this is lower than the often targeted 60% standard, web based surveys have lower response rates due largely to an overabundance of web type surveys or “survey saturation” [19]. Future considerations to improve response rates should include frequent reminders or alerts, which could have increased the current response rate; however frequent reminders or alerts will be consistent with goal for encouraging potential respondents [19]. Additionally, this low response rate may be due to the type and timing of disease and treatment; therefore a different recruitment method may be necessary in order to reduce burdens that cancer survivors already have. | |

Conclusion |

|

| This evaluation of peer mentors and patients informed the program of potential changes that were needed to improve the program. This included educational needs of patients, stressing ongoing communication between the mentor and the mentee, formalized survivorship elements into the overall program, strengthening selfadvocacy training so mentors can effectively encourage patients e.g., “questions to ask their doctors” and “paying special attention to the stage of life” and addressing “age when matching a mentor to a new patient”. Results of this study support that patient’s life experiences may be based on their developmental stage [20]. | |

| As a result of the evaluation, the changes made to the program included continued consistent restructuring of the content, curriculum and delivery styles. It also included pre and post evaluation tests of the training and in providing learning objectives with pre and posttest surveys in order to measure overall effectiveness and knowledge gains. This method of evaluation leads to a better understanding of the contexts of participant experiences and improved outcomes. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi