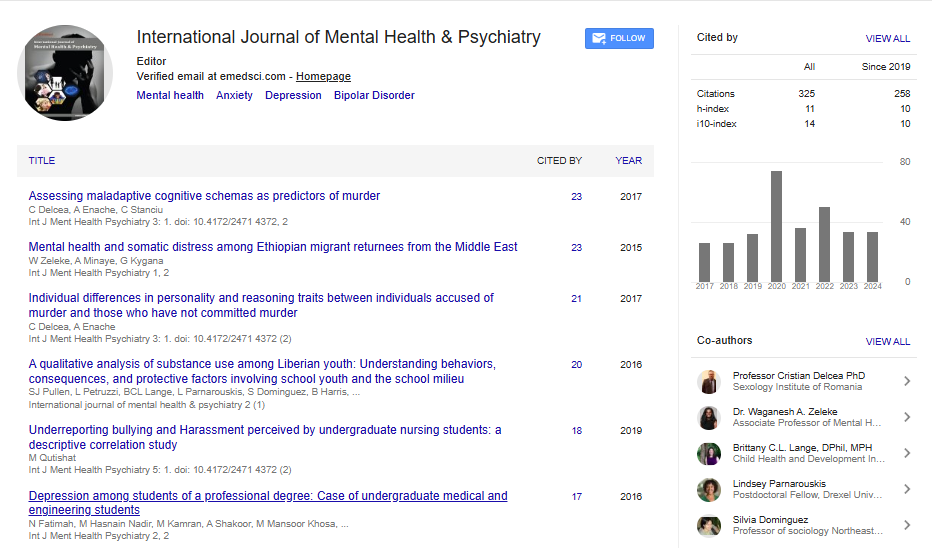

Review Article, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 6 Issue: 3

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support to Address COVID-19 in the Americas: A Strategy of Hope

Prewitt Diaz JO*Center for the Study of Psychosocial Support, Alexandria, Virginia, United States

*Corresponding Author : Prewitt Diaz JO

Center for the Study of Psychosocial

Support, Alexandria, Virginia, United States

E-Mail: jprewittdiaz@gmail.com

Received date: June 17, 2020; Accepted date: June 30, 2020; Published date: July 07, 2020

Citation: Prewitt Diaz JO (2020) Mental Health and Psychosocial Support to Address COVID-19 in the Americas: A Strategy of Hope. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 6:3. doi: 10.37532/ijmhp.2020.6(3).177

Abstract

This paper discusses the challenges of implementing Mental Health and Psychosocial Support strategies during COVID-19 in the Americas. Services strategies were modified to Information and Technology approaches. Tele-service information, and brief emotional interventions were offered, Tele-consultation and psychoeducation ere offered through webinars, and computer platforms (Teams and Zoom). Concludes with three suggestions for achieving MHPSS strategies as a strategy for hope.

Keywords: Mental health; Psychosocial support; Covid 19; Pandemic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the mental health needs of the population who, during forced quarantine, have had time to experience their human vulnerabilities, felt the fear of death, the uncertainty of getting sick, loss of trust in national system of care, the helplessness of not finding a solution to their existential problems, and the loneliness caused by the need to self-quarantine. While the physical sequelae of this event will be solved fairly soon, the mental health needs of the population will increase over time. Frontline responders can re-invent methods traditionally used to alleviate suffering and promote hope.

Frontline responders traditionally rely on international guidance to inform their response schemes such as the SPHERE project and the Mental Health and Psychosocial Support (MHPSS) originally published in 2008. These tools were later adopted as the primary tool to address community psychosocial needs especially mental health needs increase in primary and speciated care. In December 2019, the Red Cross movement approved MHPSS as a primary tool to address the emotional and psychosocial needs of the population after a major catastrophe.

This paper introduces the views of a practitioner. It also explores and documents early strategies in the use of the MHPSS as a tool to handle the mental health and psychosocial needs of a population in the Americas.

Background

The response to various global infectious disease outbreaks such as coronavirus (COVID-19) informs the formulation of a response based on MHPSS responses to these events. It leads to appropriate pyramidbased interventions proposed by the IFRC [1]. Since the highly lethal influenza pandemic outbreak in 1918 [2], there have been few global threats from infectious agents. The SARS outbreaks in Asia and Canada [3] as well as H1N1, MERS, Ebola virus [4], and the Zika virus [5-7] have provided important lessons to inform preparedness and response.

Like many crisis and disaster events, pandemics result in a predictable range of distress reactions (insomnia, decreased perception of safety, anxiety), health risk behaviors (increased use of alcohol and tobacco, work/life imbalance manifested by extreme dedication in the workplace to relieve distress), and psychiatric disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety.

Infectious outbreaks have unique characteristics that increase fear and uncertainty due to the imperceptibility of the infectious agent, uncertainty about infection, and initial symptoms that are often easily confused with more known benign diseases. As a result, pandemics manifest unique individual and community responses such as scapegoats and guilt, fear of infection, and high levels of somatic (physical) symptoms.

According to the IASC, the community's response to outbreaks is governed by the perception of risk (not the actual risk) with a variety of factors that affect community distress. This has been the case with COVID-19 [6].

Frontline health workers and volunteers are particularly vulnerable to the negative mental health effects of treating victims of COVID-19 and may experience high levels of traumatic stress reactions including depression, anxiety, hostility, and somatization symptoms. They are directly exposed to the disease and consequent community discomfort. These workers generally work long hours due to the high caseloads and the need to balance the duty to care for patients with concerns about their own well-being and that of their family and friends.

Effective public mental health measures will address numerous areas of possible distress as well as risky health behaviors and psychiatric illness. In anticipation of significant disruptions and losses, it will be imperative to promote health protective behaviors and health response behaviors. Areas of special attention include: (1) The role of risk communication; (2) The role of security communication through public/private collaboration; (3) Psychological, emotional, and behavioral responses to public education, public health surveillance, and early detection efforts; (4) Psychological responses to community containment strategies (quarantine, movement restrictions, closing of schools/work/other communities); (5) Increase and continuity of the health care service; and (6) Responses to massive prophylaxis strategies using vaccines and antiviral drugs. The recommended steps in response to a COVID-19 outbreak are divided into four phases: preparation, immediate response, recovery, and planning for the mental health intervention.

Mental Health and Psychosocial Support Interventions

Mental health and psychosocial support problems (MHPSS) are prevalent in all segments in humanitarian settings. The situation is no different in the Americas with COVID-19. The extreme stressors associated with COVID-19 increase the risk of experiencing social, behavioral, psychological, and psychiatric conditions. MHPSS comprise multi-sectoral actions. Our situation analysis evaluated available spaces in the population. Working with national societies, we show a need for health access for mental health disorders and the functional disabilities that accompany them.

While psychosocial support is a transversal theme in all areas of disaster response and recovery, the SPHERE Project (2018) [7[ recommends four major sectors for MHPSS [8] interventions: (1) Self-help and support in the community; (2) Psychological first aid (PFA); (3) Psychological interventions; and (4) Specialized mental health care. A brief description of each is below.

Self-help and support in the community

Interactions between volunteers and community leaders can lead to strategies so that all members of the community (neighborhood, community, including marginalized people, communities of faith and/or community traditions) get improved self-help and psychosocial support. Activities may include safe spaces for different sectors and/or community activities that promote dialogue in the community [9].

Psychological First Aid (PAP)

First aid is necessary for people exposed to episodes including in traumatic spaces. These include physical violence, sexual violence, witnessing deaths among family members, or who may have suffered serious trauma. It is not about clinical interventions but a basic, humane, and supportive response to our neighbors who are suffering for what they have seen and/or suffered. The PAP steps include (1) Careful listening; (2) Evaluate; (3) Guarantee basic needs; (4) Foster psychosocial support; and (5) Protect against further harm. It is not intrusive, and it is does not pressure people to talk about their discomfort. After a brief orientation, volunteers can administer PAP to the affected community. One session allows the affected person to let off steam by briefly but systematically recounting their perceptions, thoughts, and emotional reactions during a stressful episode.

Psychological interventions

Volunteers who have the proper preparation and licensure can perform psychological interventions related to depression, anxiety, and traumatic stress disorders with proper clinical supervision.

Specialized mental health care

Specialized mental health and neurology services must be identified in the location where the national society is located. Providers must be trained in accordance with protocols based on ICD-10 and/or DSM-V [10]. If possible, all national society clinics should have a psychiatric nurse. Maternal mental health is especially worrying because of the effect it can have on boys and girls.

Response

An immediate response occurs for about two months after the disaster strikes. It provides for immediate assistance for infected and affected people as well as a gestation period for the development of plans for recovery and the long-term response. These periods allow planners to consult with government, other partners, and the affected population. Gestation period allows for careful planning; capacity building to identify the local languages of distress, culture, and context; severity and duration; and development of tool boxes that are community-specific.

Education

Public education must begin immediately—even before a pandemic occurs. It can be integrated into existing public education campaigns, resources, and disaster initiatives (for example, www.ready.gov, Red Cross, CDC, public education and preparedness (HLS https: // www.cdc. Gov/flu/pandemic-resources/planning-prepareness/ national-strategy-planning.html, and HHS https: //www.cdc.gov/ flu/ pandemic-resources/index.htm). This should focus on the facts including what is known, what is not known, and how individuals, communities, and organizations can prepare for a potential outbreak. As we know from SARS and other outbreaks, public education impacts threat awareness, threat assessment, and preparedness behaviors at every phase of an event. Public education before an outbreak should include the varying degree of threats to include those with a reasonably low threat potential for those with the highest potential.

Train volunteers and leaders of national societies

Leadership training should ensure that volunteers understand, which members of the population will be most vulnerable and who will need the highest level of health services including mental health services. This includes identifying those groups that may be most at risk for contagion-related problems such as those with psychiatric illness, children, the elderly, the homeless, and those suffering from pain or loss. Negative ongoing life events also increase the risk of mental health problems and may place certain people at greater risk of having a negative impact on mental health due to COVID-19. In addition, health risk behaviors, such as smoking, drug use, and alcohol use, can increase in times of stress leading to elevated risk for some people.

Sustainable preparedness measures

Maintaining motivation, physical and social capital, equipment, and funding should be considered to continue long-term preparedness efforts—not simply to focus on immediate needs. It is important to remember that if responses are under-supported and fail, then community anger and low morale can further complicate a community's ability to respond to an outbreak as well as the recovery process once the COVID-19 outbreak has been controlled.

Leadership functions

Leadership roles require the identification of community leaders, spokespersons, and natural emerging leaders who can affect individual and community behaviors and who can support and model of protective health behaviors. Special attention should be given to the place of interventions: It is essential that public education resources potentially reach large segments of the population. The media, and community groups and faith communities, are important leaders in most modern societies and have a critical role in communication leadership.

Communication

The wide dissemination of uncomplicated and empathetic information about normal stress reactions can normalize reactions and emphasize hope, resilience, and natural recovery. Recommendations to prevent exposure, infection, or stop disease transmission will be met with skepticism, hope, and fear. These responses will vary according to the individuals and past experiences of the local community with the Red Cross. The media can promote a collaborative approach. Interactions with the media will be challenging and critical. The public must be clearly and repeatedly informed about the justification, and the mechanism for distribution of informational materials may be limited.

Key points

Certain events known as "key operating points," will occur and can dramatically increase or decrease fear and useful or health-risk behaviors. Deaths of important or particularly vulnerable people (e.g., children), new unexpected and unknown risk factors, and scarcity of treatments are typical turning points. The importance of community ritual behavior (e.g., speeches, memorial services, funerals, gathering campaigns, television specials) are important tools in managing distress and loss throughout the community.

Increased demand for psychosocial support

Those who believe they have been exposed (but have not actually been) can outnumber those exposed and can quickly overwhelm a community's medical and psychological responsiveness. Planning for psychological and behavioral responses to increase health demand, community responses to shortages, and early behavioral interventions after COVID-19 identification and prior to vaccine availability are important preparatory activities for public health.

Community structure

Important communities must be maintained. Community social support, both formal and informal, will continue to be important. Psychosocial support on a personal level may be hampered by the need to limit movement or contact due to contagion concerns. Virtual contact via phone, web, and other remote resources will be particularly important at this time. At other times, local gathering places (places of worship, schools, post offices, and grocery stores) could be access points for education, training, and distribution. Insofar as it allows, instilling a sense of normality could be effective in building resilience. In addition, observing rituals and participating in regular activities (such as school and work) could control distress and adverse behaviors in the community and organization. Providing tasks for community psychosocial support can complement necessary work resources, increase effectiveness, and instill optimism. Maintaining and organizing to keep families and community members together is important (especially in case of relocation).

Stigma and discrimination

Under conditions of continuous threat, the management of ongoing racial and social conflicts in the immediate response period and during recovery takes on additional importance. Stigma and discrimination can marginalize and isolate certain groups preventing recovery.

Fatality management

The Interagency Agencies Committee [11] state that mass death and body management should be planned as well as the community responses to such events. Body-related containment measures may also conflict with religious beliefs, burial rituals, and the usual grieving process. Local officials should consider the potential negative impact of disrupting normal funeral rituals and mourning processes to take safety precautions. MHPSS announcements should include what to do with the bodies. Funeral resources were negatively impacted in COVID-19. Careful identification of bodies must be assured and appropriate with accurate records.

Planning for Mental Health Intervention

Efforts to increase health protective behaviors and response behaviors are important. People under stress will need reminders to take care of their own health and limit potentially harmful behaviors. This includes taking medications, giving medications to the elderly and children, infection prevention measures, and when to get vaccinated. The current COVID-19 response has impacted the approach to community from a person-to-person approach to one that relies on technology to convey messages to the population. Therefore clear, precise, and timely information is critical. Risk communication should be based on risk communication principles. The media can amplify skepticism or promote a collaborative approach. Interactions with the media will be critical and challenging [12].

Good security communication

Promoting clear, simple, and easy measures can be effective in helping people protect themselves and their families.

Public education

Educating the public not only informs and prepares, but also enlists them as partners in the process and plan [13]. Education and communications should address fears of contagion, danger to family and pets, and mistrust of authority and government. The tendency to wait or act as if they are not present can delay health protection behaviors throughout the community 9 [12].

Facilitate community-led efforts

Organizing community needs and directing action towards tangible goals will help build the community's inherent resistance to recovery [14].

Use evidence-based principles of psychological first aid. These basic principles include:

• Establish security and identify safe areas and behaviors. Provide accurate and up-to-date information.

• Maximize people's ability to care for themselves and their families and provide measures that allow individuals and families to succeed in their efforts.

• Teach calming skills and maintenance of natural body rhythms (e.g., nutrition, sleep, rest, exercise). Limit exposure to traditional and social media as increased use increases distress.

• Maximize and facilitate connection to family and other social supports as much as possible (this may require electronic rather than physical presence).

• Promote hope and optimism without denying risk. Encourage activities that restore a sense of normality.

First responders, ambulance technicians, and those who manage health phone lines to maintain their function and presence in the workplace also need care. This will require assistance to ensure the safety and care of their families. First responders comprise a diverse population, which will include medically trained non-experienced bystanders (at the moment). First responders will experience increased stress from having to handle concerns about their own safety and potentially the stigma of family, friends, and neighbors [15].

Mental health surveillance includes ongoing population-level estimates of mental health problems to drive services and funding. Surveillance should address traumatic stress, depression, altered substance use, and psychosocial needs (e.g., housing, transportation, schools, employment) and the loss of critical infrastructure to maintain community functions [16,17].

Summary and Conclusion

The initial period of immediate response has changed from a person-to-person approach to the use of Information and Technology strategies to reach affected and infected people. Webinars and other media sources like WhatsApp and Instagram are used for linking, consulting, and sharing tools. They can also provide virtual safe space to reach children, the elderly, and marginalized populations. PFA is rarely done in person but rather via telecommunication. Teleconsultation between psychologist and the affected population have taken over the role of community-level PFA. Referrals for short-term sessions are being done from specialized call centers of national societies, the Red Cross, or local governments.

There are three lessons learned from practitioners at this early stage of recovery. First, the “one size fits all” tool box no longer applies. Most survivors will be distressed because COVID-19 has led to a loss of neighborhood and communities, bonds, familiarity and attachments (individually and collectively). The community will have to create new ways to express their language of distress and devise potential interventions to resolve post COVID-19 related stress. Second, retooling volunteers with PFA skills that promote calming, exploration of ritual that promote hope, and lead survivors to a new place. COVID-19 has brought much loss and tragedies to affected and infected people. Third, MHPSS is a simple paradigm that can be easily institutionalized by the national societies, the Red Cross, and local governments. The ultimate goal is to provide a sense of safety, security, calmness, and promote hope.

Neighborhoods and communities will never be the same. The role of the volunteer becomes crucial in psychosocial support at the community level. People will continue to mourn their physical, spiritual, and emotional losses. Letting go of rituals from life before COVID-19 and embracing the new reality must occur in long-term recovery to foster psychological rebuilding based on hope for a brighter and safer future. Calmness and stability allow people to develop knowledge for this new lifestyle. This can lead to trusting relationships with new neighbors or re-establishing trust with old neighbors.

After COVID-19, affected and infected people will need a calming environment that will offer them trusting relationships with each other; reintegration with the physical and psychological community; and recovery of neighborhood, faith-based relationships, and community-wide friendships.

References

- IFRC PSP Reference Centre (2020) Key actions on caring for volunteers in COVID-19: mental health and psychosocial considerations. Copenhagen: DK. IFRC Psychosocial Centre.

- Crosby AW (2004) America's Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918. Cambridge University Press.

- Blendon RJ, Benson JM, DesRoches CM, Raleigh E (2004) The Public's Response to Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Toronto and the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases 38: 925–931.

- Alessandri C, Zoumanigui K (2017) The first Psychosocial Procedure in Zenie. In: Prewitt Diaz JO, Warentown NJ (eds) Disaster Recovery: Community Based Psychosocial Support in the Aftermath: Apple Academic Press: 197-218.

- Prewitt Diaz JO (2017) Psychosocial Support and Epidemic Control Interface: A Case Study. In: Prewitt Diaz JO, Warentown NJ (eds) Disaster Recovery: Community Based Psychosocial Support in the Aftermath. Apple Academic Press 197-218.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee (2007) IASC Guidelines on Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergency Settings. Geneva. IASC.

- Sphere Association (2018) The Sphere Handbook: Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Humanitarian Response (4th ed), Geneva. pp: 374-379.

- International Organization for Migration (IOM) (2019) Manual on Community-based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergencies and Displacement. Geneva, IOM. ISBN 978-92-9068-784-9.

- WHO/PAHO (2019) mhGAP Community Tool Kit: Field Test version. Geneva: World Health Organization.

- WHO/PAHO (2015) mhGAP Humanitarian Intervention Guide (mhGAP-HIG): clinical management of mental, neurological and substance use conditions in humanitarian emergencies. Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 154892 2.

- IASC (2020) Addressing Mental Health and Psychosocial Aspects of COVID-19 outbreak (Version 1.5). Geneva. Inter-Agency Standing Committee.

- IFRC PSP Centre (2020) Salud Mental y ApoyoPsicosocialpara el personal, los voluntarios y lascomunidades en un brote del Nuevo Coronavirus. Copenhagen: DK. IFRC Psychosocial Centre.

- Prewitt Diaz JO (2020) Timely Community Psychosocial Support during the Coronavirus Outbreak: A practical response. International Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 2.

- IOM (2020) Manual on Community-Based Mental Health and Psychosocial Support in Emergencies and Displacement. IOM, Geneva.

- IFRC PSP Reference Center (2017) El Cuidado de los Voluntarios. Copenhagen, DK. IFRC Psychosocial Centre.

- IFRC PSP Reference Centre (2014) Strengthening Resilience: A global selection of psychosocial interventions. Copenhagen, DK. IFRC Psychosocial Centre.

- Mena I, Nelson MI, Quezada-Monroy F, Dutta J, Cortes-Fernández R, et al. (2016) Origins of the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic in swine in Mexico. eLife 5: e16777.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi