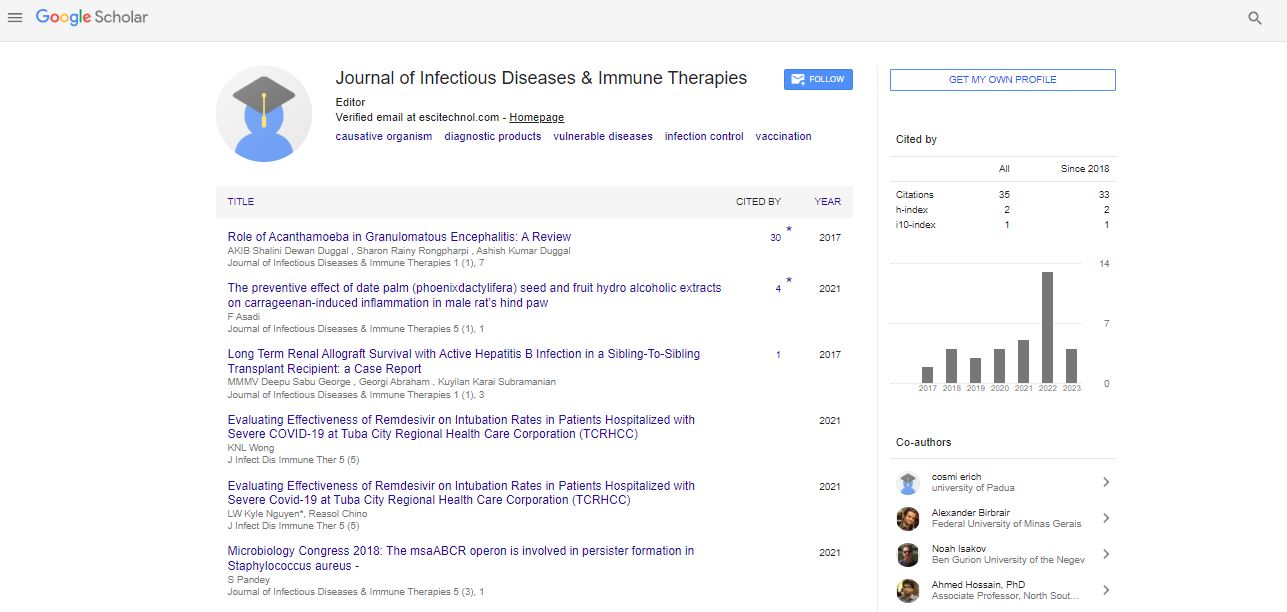

Case Report, J Infect Dis Immune Ther Vol: 1 Issue: 1

Long Term Renal Allograft Survival with Active Hepatitis B Infection in a Sibling-To-Sibling Transplant Recipient: a Case Report

Deepu Sabu George1, Georgi Abraham1*, Kuyilan Karai Subramanian2, Milly Mathew1 and Madhusudan Vijayan1

1Department of Nephrology, Madras Medical Mission, Chennai, India

2Department of Medicine, Littleton Regional Hospital, Littleton, New Hampshire, USA

*Corresponding Author : Georgi Abraham

Department of Nephrology, Madras Medical Mission, Chennai, India

Tel: 009810523332

E-mail: abraham_georgi@yahoo.com

Received: November 24, 2017 Accepted: December 15, 2017 Published:December 20, 2017

Citation: George DS, Abraham G, Subramanian KK, Mathew M, Vijayan M (2017) Long Term Renal Allograft Survival with Active Hepatitis B Infection in a Sibling-To-Sibling Transplant Recipient: a Case Report. J Infect Dis Immune Ther 1:1.

Abstract

Here we report on a 69-year old man with a well-functioning kidney transplant 25 years post-transplant, with active hepatitis B viral replication. The recipient was not inducted and received oral prednisolone, azathioprine and cyclosporine as maintenance therapy. He was detected to be hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive on routine screening in the early period following transplantation and his donor younger brother was also detected to be HbsAg positive. Recipient could not afford anti-viral drugs initially. Hepatitis B viral load was detected to be 2.2 × 1010 viral copies/ml 21 years after transplantation with good allograft function. He took lamivudine 100 mg once a day for the next 6 months, and then discontinued and was followed up with yearly with liver function tests, alpha-feto protein (AFP), ultrasound examination of the abdomen with a specific focus on liver. His current allograft function showed a serum creatinine 1.1 mg/dl, blood urea 20.6 mg/dl and his urine examination are normal. He is well and leading a normal life and his current viral load is >107 copies / ml.

Keywords: Hepatitis B; Allograft survival

Introduction

Approximately 240 million people have been infected worldwide with hepatitis B (HBV) virus. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) with HBV co-infection is widely prevalent in developing countries of South Asia [1]. The prevalence of hepatitis B carrier state is 4% in India [2]. Lifestyle and other health related factors in different parts of the country may explain the variations in carrier rates. Lack of awareness and poor vaccination status in CKD patients predispose particularly the Indian population to a state of higher prevalence. Blood transfusions and reuse of injection needles are predominant causes of transmission of HBV; however, organ transplantation is still an under-recognised cause of transmission from an undetected HBV donor to the recipient. Achieving sustained viral remission (SVR) in HBV infection is a major goal before renal transplantation. Newer antiviral drugs, though expensive can achieve SVR [3]. CKD patients who are HBV positive do well after transplant given the availability of newer antiviral drugs. The risk of hepatic dysfunction is high due to a higher viral load, concomitant use of hepatotoxic molecules including immunosuppressive agents such as calcineurin inhibitors (CNI), azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil (MMF), and mTOR inhibitors. We present a case of a male CKD patient who underwent a sibling renal transplantation in 1992 and was detected to be an HBV carrier. He still has an excellent allograft function and normal liver function despite a high hepatitis B viral load 25 years post-transplant.

Case Report

A 69-year male CKD patient underwent live related renal transplantation from his younger brother on February 12, 1992 at the age of 45 years. The recipient was on haemodialysis for 5 months prior to transplantation. Both donor and recipient had the same blood group (B positive). HLA typing was not done due to unavailability of facilities. Viral markers for HIV-1 and 2, HBsAg and Anti-HCV antibodies were negative prior to transplant. Following a tooth extraction prior to surgery, the recipient had severe bleeding which required transfusion of 3 units of packed red blood cells. He was not inducted but was given an injection of methylprednisolone 1000 mg on the day of surgery, followed by 500 mg the next two days. He was then started on prednisolone 50 mg once a day, azathioprine 100 mg once a day and cyclosporine 125 mg twice a day; all of which were tapered subsequently. The post-operative period was uneventful with a baseline serum creatinine of 0.8 mg/dl. The recipient was found to be HBsAg positive on routine screening in the early period of transplantation. His brother who was the donor was found to be positive for HBsAg at the same time. The donor became seronegative spontaneously after many years.

Potent and diverse anti-viral drugs available in the 90’s was advised following transplant but the recipient could not take any anti-viral drugs due to lack of affordability. He worked for a multinational company as a junior accountant, who provided him with health insurance for regular investigations and immunosuppressive drugs until his retirement. The patient underwent testing of his hepatitis B viral load in August 2013 sponsored by our hospital which was found to be 2.2 × 1010 viral copies per ml. Following this, he took lamivudine 100 mg once a day for the next 6 months and a viral load was rechecked. Viral load in March 2014 was showing more than 1.7 × 108 copies per ml. He discontinued the antiviral drugs following this report.

His current immunosuppressive medications include prednisolone 5 mg once a day and cyclosporine 25 mg twice a day. His allograft function showed a serum creatinine of 1.1 mg/dl, urea of 20.6 mg/dl and his urine examination were unremarkable (Table 1, figure 1). Physical examination was normal with a blood pressure of 136/84 mm of Hg, heart rate of 80 beats per minute and unremarkable examination of the systems. His complete blood count (CBC) was normal, hemoglobin at 14.4 g/dl and BMI of 25.9 kg/m2. He teaches and practices yoga daily.

| INVESTIGATIONS | RESULTS | REFERENCE RANGE |

|---|---|---|

| Fasting Blood Sugar | 91 | <100 mg/dl |

| Post Prandial Glucose (2 hrs) | 181 | 90-130 mg/dl |

| Urea | 20.6 | 19-43 mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 1.1 | 0.7-1.3 mg/dl |

| Uric Acid | 3.7 | 3.4 – 7.0 mg/dl |

| LIPID PROFILE | ||

| Total Cholesterol | 185 | <200 mg/dl |

| Triglycerides | 73 | <150 mg/dl |

| HDL | 68 | >60 mg/dl |

| LDL | 113 | 100-129 mg/dl |

| VLDL | 15 | 5 – 30 mg/dl |

| LIVER FUNCTION TEST | ||

| Total Bilirubin | 0.7 | 0.2 – 1.3 mg/dl |

| Direct Bilirubin | 0.2 | 0.0 – 0.3 mg/dl |

| SGOT(AST) | 26 | 15 - 46 IU/L |

| SGPT(ALT) | 37 | 13 - 69 IU/L |

| Alkaline Phosphatase | 70 | 38 – 126 IU/L |

| Gamma GT | 35 | 15 – 73 IU/L |

| Total protein | 6.3 | 6.4 – 8.3 mg/dl |

| Serum albumin | 3.6 | 2.5 – 5.0 mg/dl |

| Globulin | 2.7 | 2.0 – 3.5 mg/dl |

| A/G ratio | 1.3 | |

| ELECTROLYTES | ||

| Sodium | 137 | 137-145 mEQ/L |

| Potassium | 3.8 | 3.5-5.1 mEQ/L |

| Chloride | 101.4 | 98-107 mEQ/L |

| COMPLETE BLOOD COUNT | ||

| Hemoglobin | 15.2 | 13.7-17.5 g/dl |

| Total count | 9300 | 4000-10000 cells/cmm |

| RBC count | 4.74 | 4.63-6.0 millions/cmm |

| Packed cell volume | 45.1 | 40.1-50.0% |

| MCV | 95.1 | 79.0-92.2 fl |

| MCH | 32.1 | 27-32 pg |

| MCHC | 33.7 | 32-36% |

| Platelet count | 2.27 | 1.5-4.0 lakh/cmm |

| DIFFERENTIAL COUNT | ||

| Polymorphs | 63.3 | 40-60% |

| Lymphocytes | 26.2 | 20-40% |

| Monocytes | 6.6 | 1-10% |

| Eosinophils | 3.6 | 0-6% |

| Basophils | 0.4 | 0-1% |

| ESR | 5 | 12 mm |

| URINE ROUTINE | ||

| Colour | Pale yellow | Pale yellow to yellow |

| Appearance | Clear | Clear |

| pH | 6.0 | 4.6 – 8.0 |

| Specific gravity | 1.015 | 1.003 – 1.035 |

| Protein | Absent | Absent |

| Glucose | Absent | Absent |

| Ketone | Absent | Absent |

| Nitrite | Absent | Absent |

| Bile pigments | Absent | Absent |

| Urobilinogen | Present in normal limits | Normal |

| URINARY DEPOSITS | ||

| Pus cells | 6-8 | 0 – 5 cells/hpf |

| Epithelial cells | 2-4 | 0 – 5 cells/hpf |

| RBCs | Not detected | 0 – 3 cells/hpf |

| Casts | Not detected | Absent |

| Crystals | Not detected | Absent |

| Others | Not detected | |

Table 1: Laboratory investigations done for the recipient in July 2017 (25 years post-transplant).

The recipient was followed up with every year with liver function tests, alpha-feto protein (AFP), ultrasound examination of the abdomen specifically focusing the liver which are within normal limits (Table 1, figures 1-3). He is well and leading a normal life with no complications of the high viral load in his blood. His current viral load (July 2017) is more than 107 copies/ml. Liver biopsy was not done; instead, fibroscan of the liver was done (figure 3).

Figure 3: FIBROSCAN is a test that is done to reveal any fibrosis or fatty deposits within the liver cirrhosis. It is a non-invasive investigation which is quick and simple that works using ultrasound and measures the median stiffness of liver. Value more than 12.5 kPa is suggestive of cirrhosis. In our patient, the fibroscan shows a median stiffness of 6.1 kPa, which is suggestive of no significant liver disease.

Discussion

Hepatitis B viral (HBV) infection is recognized as an independent risk factor for graft failure and mortality in kidney transplant recipients (KTRs) [4-7]. Renal transplantation is the best form of RRT for patients with hepatitis B carrier state irrespective of either dormant or slowly multiplying hepatitis B. Chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients with HBV infection require adequate antiviral therapy prior to transplantation to establish sustained viral remission (SVR). Our patient is a 68-year-old male who received a renal allograft 25 years ago from his brother and was detected with HBV infection post transplant. The donor brother was tested negative for HBsAg prior to transplantation. However, he might have been in the seroconversion stage during testing. The recipient continues to have a high viral load with good allograft function even after 25 years. He has normal liver functions. However, fibroscan of his liver done recently shows a mean stiffness of 6.1 kPa (figure 3) suggestive of no significant liver disease.

Immunosuppression in KTRs following primary infection from an HBsAg+ or anti-HBcore+ donor markedly enhances HBV replication rate leading to rapid progression of liver fibrosis. Before the availability of safe, effective antiviral therapy, primary HBV infection following transplantation usually resulted in liver failure and death. Kidney Disease-Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) Transplant Group guidelines suggest the use of any the currently available induction and maintenance immunosuppressive medication in HBsAg positive KTRs [8]. Newer antiviral agents Entecavir and Tenofovir have been successful in achieving SVR and hence is used in most patients [1]. The recipient in our case took lamivudine for 6 months in 2013 but was unable to continue the treatment due to financial constraints. However, he underwent yearly screening for hepatic dysfunction or malignancy and random count of HBV viral load.

Our patient was probably in the window period at the time of transplantation when he was first tested negative for the hepatitis B surface antigen. His donor brother who was also infected most likely transmitted the infection through kidney transplantation. He was later tested to be positive for HBsAg but became negative spontaneously without any antiviral drugs. Recipient’s viral loads were always in the high millions and never came down.

He never developed a single episode of rejection. He is healthy with a well-functioning graft (Table 1, figure 2) and with no hepatic dysfunction or malignancy. In a case control study by Mathurin [3] both 10-year graft and patient survival were significantly lower in HBV infected patients [3]. In a natural history study, 151 HBsAg positive kidney transplant recipients developed a high rate of histological deterioration (85.3%), accompanied by cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Despite persistent viral replication, histopathologic deterioration, and liver-related over mortality, there were paradoxically no significant differences in the survival of these 151 HBsAg-positive compared with 1247 HBsAg-negative kidney recipients - however, allograft survival was better in the former than in the latter group [4].

Whether the presence of high viral load in his blood gives him protection against developing graft rejection or dysfunction of any kind over the last 25 years is something that needs to be pondered about. There is no evidence to recommend transplantation in patients with active hepatitis B replication, but studies at the molecular level are required to address this question based on this unique patient.

References

- Puri P (2014) Tackling hepatitis B disease burden in India. J Clin Exp Hepatol 4: 312-319.

- Tandon BN, Acharya SK, Tandon A (1996) Epidemiology of Hepatitis B virus Infection in India. v GUT 38: 56-59

- Pilmore HL, Gane EJ (2012) Hepatitis B–Positive Donors in Renal Transplantation: Increasing the Deceased Donor Pool. Transplant 94: 205-210.

- Mathurin P, Mouquet V, Poynard T, Sylla C, Benalia H (1999) Impact of hepatitis B and C virus on kidney transplantation outcome. Hepatology 29: 257-263.

- Fornairon S, Pol S, Legendre C, Carnot F, Mamzer-Bruneel MF(1996) The long-term virologic and pathologic impact of renal transplantation on chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Transplant 62: 297-299.

- Lee WC, Shu KH, Cheng CH, Wu MJ, Chen CH, Lian J (2001) Long-term impact of hepatitis B, C virus infection on renal transplantation Am J Nephrol 21: 300-306.

- Breitenfeldt MK, Rasenack J, Berthold H, Olschewski M, et al. (2002) Impact of Hepatitis B and C on graft loss and mortality of patients after kidney transplantation. ClinTransplant 16:130-136

- Margaret B, Deborah BA, Roy DB, Laurence C (2010) KDOQI US Commentary on the 2009 KDIGO Clinical Practice Guideline for the Care of Kidney Transplant Recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 56: 189-218.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi