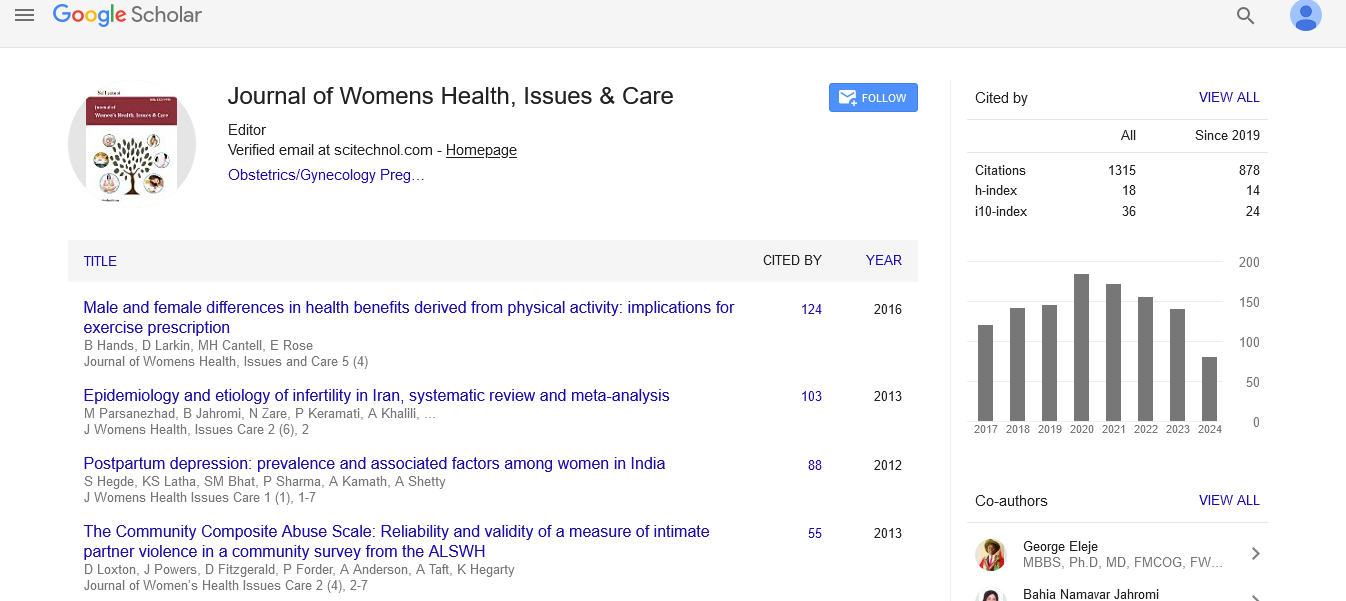

Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 3 Issue: 5

Gender Differences in Perceived Risks and Benefits of Quitting Smoking among Korean Americans

| Sun S Kim* | |

| Department of Nursing, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Boston, USA | |

| Corresponding author : Sun S Kim Department of Nursing, College of Nursing and Health Sciences, University of Massachusetts, Boston MA, USA Tel: 508-856-6384 Email: Sun.Kim@umassmed.edu |

|

| Received: April 14, 2014 Accepted: August 18, 2014 Published: August 22, 2014 | |

| Citation: Kim SS (2014) Gender Differences in Perceived Risks and Benefits of Quitting Smoking among Korean Americans. J Womens Health, Issues Care 3:3. doi:10.4172/2325-9795.1000160 |

Abstract

Gender Differences in Perceived Risks and Benefits of Quitting Smoking among Korean Americans

Tobacco dependence is the leading cause of increased morbidity and mortality in many countries. It is estimated that tobacco use will cause approximately 450 million deaths worldwide during the next 50 years. Men in Korea are known for the highest rate of smoking in the world and subsequently Korean male immigrants smoke at a higher rate than the general U.S. male population. Based on a recent population-based tobacco survey in New York City, the rate of smoking among foreign-born Korean men was 36% versus 16% for the whole city male population.

Keywords: Perceived risks benefits; Gender; Smoking cessation; Quit intention; Asian american

Keywords |

|

| Perceived risks benefits; Gender; Smoking cessation; Quit intention; Asian american | |

Abbreviation |

|

| PBRQ: Perceived Risks and Benefits Questionnaire | |

Introduction |

|

| Tobacco dependence is the leading cause of increased morbidity and mortality in many countries. It is estimated that tobacco use will cause approximately 450 million deaths worldwide during the next 50 years [1]. Men in Korea are known for the highest rate of smoking in the world and subsequently Korean male immigrants smoke at a higher rate than the general U.S. male population [2]. Based on a recent population-based tobacco survey in New York City, the rate of smoking among foreign-born Korean men was 36% versus 16% for the whole city male population [3,4]. Although the rate of smoking among Korean American women is slightly lower than that of the general U.S. female population, they have the highest rate of all Asian American women [3,5]. | |

| Perceived risks of quitting smoking (e.g., nicotine withdrawal symptoms and weight gain) and perceived benefits of quitting smoking (e.g., improved health, social approval, and finances) are important research subjects because they were found to affect quit intention and cessation outcomes [6,7]. McKee et al. [6] developed the Perceived Risks and Benefits of Questionnaire (PRBQ) that assesses specific beliefs and anticipated outcomes (both positive and negative) associated with quitting smoking. Based on empirical research findings, the benefits were positively related to quit intention and cessation outcomes, whereas the risks were negatively related [6-8]. These findings support the proposition of the Theory of Planned Behavior that behavioral and normative beliefs lead to intention to engage in a particular behavior, which, in turn, leads to the desired outcome of the behavior (e.g., abstinence) [9]. | |

| The theory of Planned Behavior posits attitudes, perceived social norms, and self-efficacy are the main antecedents to behavior change [9]. Here attitudes are defined as the degree to which a person has a favorable or unfavorable evaluation or appraisal of the behavior in question (e.g., quitting smoking); (b) perceived social norms are defined as the individual’s perception of social pressures to perform the behavior; and (c) perceived behavioral control refers to the perceived ease or difficulty of performing the behavior. The theory proposes that the more favorable attitudes and perceived social norms and the greater the individual’s perceived behavioral control toward the behavior, the stronger behavioral intention to perform the behavior should be. The PRBQ assesses one’s attitudes toward quitting smoking. | |

| Significant gender differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking have been reported among general U.S. smokers who were seeking treatment for smoking cessation [6,8]. Compared to men, women perceived greater risks (e.g., weight gain, negative affect, and attention/concentration problems) and greater benefits (e.g., self-esteem, general well-being, health, and finances) of quitting smoking [6]. The relationship between the risks and motivation to quit smoking was much stronger for women than for men, which means that women were far less motivated to quit smoking than men even when the two groups endorsed the same level of the risks. On the other hand, non-treatment seeking smokers showed no gender differences in the risks and benefits except for women having more weight concerns than men [10]. Compared to treatment seeking smokers, non-treatment seeking smokers generally endorsed lower ratings of perceived risks and perceived benefits of quitting smoking [10]. | |

| There is a strong gender-based social norm toward smoking in Korea. Men typically become regular smokers as a rite of passage to adulthood when they graduate from high school or during mandatory military service [11,12]. Thus, being a smoker is a prime component of male gender identity and Korean men assert that the foremost benefit of smoking is its attendant social interaction with other men [12]. In contrast, there is a strong social taboo against smoking by women in Korea. Women who smoke are considered unfit for marriage and motherhood [12,13]. It is not unusual to see Korean women subjected to harsh treatment such as being slapped in the face when they smoke in public [14]. Thus, Korean women are likely to underreport their use of tobacco. For example, a recent population-based survey in Korea showed a striking gender difference in the underreporting of smoking (58.9% for women versus 12.1% for men) when self-report data were compared with urinary cotinine levels using the cutoff level of 50 ng/ml [15]. Smoking rates for women increased from 5.9% by self-report to 13.9% by urinary cotinine test, whereas the rates for men increased from 44.7% to 50.0% [15]. | |

| Despite the strong social taboo against smoking by women within the Korean community, many Korean women initiated smoking and in-depth interviews identified the following top three reasons for their initiation of smoking [16]. First, many started smoking out of curiosity after having seen their husbands or partners smoke. Second, some smoked to deal with stresses including acculturative stresses. Third, young women believed that the cultural proscription against only women’s smoking is not fair. Nevertheless, women who were raised in Korea and migrated to the United States are deeply concerned about how other Koreans such as mother-in-law, friends, and co-workers would perceive them if they find out they smoke. Thus, most Korean women who smoke make every effort to cover up their smoking [17]. | |

| The present study aimed to examine gender differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking among Korean American smokers and their relationships with quit intention and any gender-interaction effects on the relationships. Given the strong gender-based social norm toward smoking, the group might have more gender-specific perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking than general U.S. smokers. The study also aimed to test any differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking among Korean Americans by their treatment seeking status. This information may help health professionals plan and implement gender-specific cessation interventions for the group. | |

Methods |

|

| Subjects | |

| Participants were Korean Americans who were selected from two studies: The first was a smoking cessation study with 131 Korean Americans who had smoked at least 10 cigarettes per day [17] and the second was a telephone survey on factors associated with quit intention among 262 Korean Americans who reported smoking daily [18]. The cessation study was conducted with a convenience sample of Korean Americans, whereas the survey study was conducted with a random sample selected from an online telephone directory listed under Korean surnames such as “Kim” and “Park”. Participants in the first study were seeking cessation treatment, whereas those in the second study were not. The rate of response among those who were screened and determined to be eligible for participation was 74.0% for the cessation study and 63.8% for the survey study. Both studies were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Massachusetts Medical School. Detailed descriptions of the two studies have been published elsewhere [17,18]. | |

| In this study, participants were restricted to those who migrated from Korea and administered research questionnaires in Korean. They might be more knowledgeable of the gender-based social norm of smoking in their native country and hence, they might have more gender-specific perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking than those who administered the questionnaires in English. Data from one woman in the cessation study and 18 women and 23 men in the survey study were excluded. | |

| Measures | |

| Prior to the use of the PRBQ (the measure of perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking), a Korean version was developed through a rigorous process of translation and back-translation. First, two Korean natives (the author and her colleague) who earned doctoral degrees in the United States independently translated the measure into Korean. The two then met and compared their Korean translations of each item. Among the 40 items, eight were translated into different Korean words that were similar in meaning. They resolved the differences in six of the eight items but could not decide which Korean translation was better for the following two items: “My thoughts will be more likely to wonder” and “My breath will be fresher”. A third person who was a doctoral student translated back the Korean version to English. He had not seen the original English measure. Six items (e.g., “I will have a shorter attention span” and “I will feel more energetic”) had different English words from the original ones but similar in meaning. After the back translation, the three people had a conference call and discussed six problematic items and the two items with two different Korean translations. For example, through discussion and agreement, they decided to keep the word “energetic” with Korean phonetics for the item “I will feel more energetic” because nearly all Korean Americans know its meaning and there is no comparable Korean word. A revised Korean version was then pilot-tested with five smokers who were not participants of the two original studies. Based on feedback from the participants, the author revised two items for the flow and finalized a Korean version of the PRBQ. | |

| Demographic and smoking information | |

| Participants were asked to provide the following information: gender, age, marital status, education, employment status, and acculturation. History of smoking and quitting was assessed in the following areas: age of regular smoking, the average number of cigarettes smoked per day, indoor house smoking, and any quit attempts made and lasted at least 24 hours within the past year. Nicotine dependence was assessed using the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence [19]. | |

| Perceived Risks and Benefits Questionnaire (PRBQ) | |

| The PRBQ consists of two scales: Perceived Risks (18 items) and Perceived Benefits (22 items) [6]. The questionnaire asks smokers to rate how likely each item would be if they were to stop smoking. Perceived Risks (e.g., “I will be less able to concentrate,” and “I will miss the taste of cigarettes”) has six dimensions: weight gain, negative affect, attention/concentration, social ostracism, loss of enjoyment, and craving, and Perceived Benefits (e.g., “I will smell cleaner,” and “I will feel proud that I was able to quit”) also has six dimensions: health, general well-being, self-esteem, finances, physical appeal, and social approval. Items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale (“1” = no chance at all, “7” = certain to happen). The scale score was estimated by averaging the scores of the 18 items for Perceived Risks and the scores of the 22 items for Perceived Benefits. | |

| Quit intention | |

| The variable was assessed using a 4-item, 7-point Likert-type scale (e.g., “I intend to quit smoking within the next two weeks,” and “I will make an effort to quit smoking within the next two weeks”) [20]. Scores for each item can range from ‘1 = most unlikely’ to ‘7 = most likely’ and the scale score is the average of the scores of the four items. In this study, the variable was dummy-coded with “1” (the total score ≥ 5, having an intention to quit) and “0” (the total score < 5, having no intention to quit or unsure) because the scale score had a positive parabola distribution. | |

| Data analysis | |

| All variables were assessed for skewness, kurtosis, and violations of normal distribution. Data were analyzed using the Statistical Program for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 21. Demographics and key variables were compared between the two studies and then between women and men by combining the two studies. Independent-samples t-tests were performed to examine differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking by gender in each study. Finally, combining the two studies, a multivariate binomial logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relationships between the risks and quit intention and between the benefits and quit intention, and any gender-interaction effects with the risks and benefits on quit intention. For the interaction effects, the variables were centered to correct possible multicollinearity. | |

Results |

|

| Demographics and key variables are compared between the two studies (Table 1). The proportion of female participants was much smaller in the cessation study than in the survey study (X2 [3,351] = 9.18, p < 0.01). The cessation group had more years of education (t349 = 3.45, p < 0.01), smoked more heavily (X2 [3,351] = 18.29, p < 0.001), and had higher nicotine dependence scores (t349 = 3.81, p < 0.001) than the survey group. Although overall perceived risks of quitting smoking did not differ, the cessation group perceived lower risks of craving (t349 = -3.84, p < 0.001) but higher risks of social ostracism (t349 = 4.09, p < 0.001) and weight gain (t349 = 3.01, p = 0.003) than the survey group. The cessation group had greater overall perceived benefits of quitting smoking (t349 = 4.54, p < 0.001) than the survey group. More specifically, the cessation group perceived greater benefits of finances (t349 = 2.28, p = 0.023), general well-being (t349 = 4.09, p < 0.001), selfesteem (t349 = 6.53, p < 0.001), and social approval (t349 = 3.67, p < 0.001) than the survey group. The cessation group was also far more likely to have a quit intention than the survey group (87% versus 39%, X2 [1,351] = 23.38, p < 0.001). | |

| Table 1: Comparison of demographics and study variables between the two studies. | |

| Demographics and key variables are compared between women and men by combining the two studies (Table 2). Compared to men, women were younger (t349 = -2.84, p <0.01), unmarried (X2 [2,351] = 40.23, p <0.001) and uneducated (t349 = -4.72, p <0.001). Women initiated smoking 3 years older on average (t349 = 2.78, p <0.01) and reported more indoor-house smoking (X2 [1,351] = 23.38, p <0.001) than men. Although women were more likely to be mild smokers than men (X2 [3,351] = 15.92, p <0.01), the two showed no difference in nicotine dependence. Women perceived greater risks (t349 = 2.38, p <0.05) and greater benefits (t349 = 2.18, p <0.05) of quitting smoking than men. Women were also less likely to have a quit intention (X2 [1,351] = 8.55, p <0.05) than men. | |

| Table 2: Comparison of demographics and key variables by gender. | |

| Perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking were compared by gender in each study group (Table 3). In both study groups, overall perceived benefits of quitting smoking differed by gender; however, overall perceived risks of quitting smoking showed only a tendency. Compared to men, women in the cessation group endorsed higher ratings of negative affect (t128 = 3.55, p = 0.001), finances (t128 = 2.34, p = 0.021), general well-being (t128 = 2.02, p = 0.045), physical appeal (t128 = 2.84, p = 0.005), self-esteem (t128 = 2.28, p = 0.024), and social approval (t128 = 2.06, p = 0.041). In the survey group, women had higher ratings of social ostracism (t219= 2.97, p = 0.003), weight gain (t219 = 4.17, p < 0.001), finances (t219= 3.02, p = 0.003), and physical appeal (t219 = 2.07, p = 0.040) than men. These differences remained significant even after adjusting for other covariates. For example, the relationship between gender and finances in the survey group was significant (p = 0.013) even after adjusting for current age that was correlated with gender and finances. | |

| Table 3: Low molecular weight PAI-1 antagonists. | |

| Gender, perceived risks of quitting smoking, and perceived benefits of quitting smoking were all significant predictors of quit intention in a multivariate regression analysis (Table 4). None of the demographics and smoking-related variables was associated with quit intention. Female smokers had 56% less odds for having a quit intention than male smokers. For male smokers, a one-unit increase in the score of the perceived risks yielded a 29% decrease in the odds for having a quit intention, whereas a one-unit increase in the score of the perceived benefits yielded a 243% increase in the odds for having a quit intention. There was a significant gender-interaction effect on the relationship between the benefits and quit intention. For a one-unit increase in the score of the benefits, the odds for female smokers to have a quit intention were 52% lower than males. In other words, the relationship between the benefits and quit intention was two times stronger for men than for women. | |

| Table 4: A multivariate regression analysis for factors associated with quit intention among Korean Americans (N = 351). | |

Discussion |

|

| To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study reporting gender differences in perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking among Korean Americans. Korean female smokers perceived greater risks and greater benefits of quitting smoking than Korean male smokers. Korean male smokers or Korean smokers who perceived lower risks or greater benefits of quitting smoking were more likely to have a quit intention than their respective counterparts. Furthermore, the relationship between the benefits and quit intention was much stronger for Korean male smokers than for Korean female smokers. In contrast, a study conducted with general U.S. smokers found a gender-interaction effect on the relationship between perceived risks of quitting smoking and quit intention and the relationship was stronger for U.S. female smokers than for U.S. male smokers [6]. | |

| The cessation group had a significant gender difference in overall perceived benefits of quitting smoking and a tendency toward a gender difference in overall perceived risks of quitting smoking. The failure to achieve a statistical significance in the latter might be related to the small sample of women in the study. These findings are supportive of those from a cessation study with general U.S. smokers [6,8]. However, findings pertaining to non-treatment seeking smokers differed in many aspects between Korean and general U.S. smokers. Korean smokers showed gender differences in overall of perceived benefits of quitting smoking and four dimensions of the risks and benefits (social ostracism, weight gain, finances, and physical appeal), whereas general U.S. smokers showed no gender difference except for weight gain [10]. This difference may stem from the strong gender-based social norm toward smoking in Korea. For example, Korean female smokers perceived greater risks of social ostracism after quitting than Korean male smokers. A possible explanation might be that Korean female smokers could have strong comradeship with one another while smoking against the social norm. They might fear that they would be no longer welcomed by other Korean female smokers once they quit smoking. | |

| Korean women in both study groups endorsed greater overall perceived benefits of quitting smoking and more perceived benefits of finances and social approval than Korean men. Nevertheless, Korean women were far less likely than their male counterparts to have a quit intention. The relationship between the benefits and quit intention was much stronger for Korean male smokers than for Korean female smokers. These gender differences could be in part related to the strong genderbased social norm toward smoking. Of note, a large number of Korean women in the survey study reported that they were afraid to make another quit attempt because they suffered from terrible withdrawal symptoms in their past quit attempts [16]. They were less likely than Korean men to seek professional assistance for quitting due to the fear of disclosing their smokers’ status to other Koreans in the community [17]. Thus, smoking cessation interventions for Korean women should be geared toward assuring confidentiality, alleviating withdrawal symptoms, and addressing other perceived risks of quitting smoking. For Korean male smokers, the intervention should be concentrated on emphasizing health and other perceived benefits of quitting smoking. | |

| One limitation of this study is a small female sample in both studies. This might have contributed to insignificant gender differences in some areas of perceived risks and benefits of quitting smoking. Future studies should be conducted with large samples of Korean female smokers and examine whether more gender differences could be found than those reported. Cessation intervention strategies for Korean Americans should be designed to modify gender-specific beliefs associated with quit intention. Healthcare providers should be aware that Korean women are more likely to hide their smoking and may not respond well to the intervention that is solely focused on facilitating perceived benefits of quitting smoking. In contrast, facilitating the perception of cessation benefits may be an effective intervention strategy to motivate Korean men for smoking cessation. | |

Funding |

|

| This work was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5K23DA021243-02) and American Lung Association (SB78709-N). The contents are solely the responsibility of the author and do not represent the official views of the institutes. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi