Case Report, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 7 Issue: 3

Evaluation of a Palpable Breast Mass in a Young Female: Implications when Working with Underserved Populations

Liz Juarez1 and Susan Chaney1*

Texas Woman’s University, 5500 Southwestern Medical Ave, Dallas, TX 75235, USA

*Corresponding Author : Susan Chaney, MS, APRN, FNP-C

Texas Woman’s University, 5500 Southwestern Medical Ave, Dallas, TX 75235, USA

Tel: 214-689-6551

E-mail: schaney@twu.edu

Received: April 23, 2018 Accepted: May 30, 2018 Published: June 04, 2018

Citation: Juarez L (2018) Evaluation of a Palpable Breast Mass in a Young Female: Implications when Working with Underserved Populations. J Womens Health, Issues Care 7:3. doi: 10.4172/2325-9795.1000313

Abstract

We report the case of a 37 year-old uninsured African American female who came to the office complaining of a breast mass for about a month. The patient was examined during the initial office visit and proper imaging was ordered based on current guidelines for this type of complaint. Literature shows that female patients who present to primary care providers with breast symptoms, approximately 42 percent of them report a breast mass. Even though most masses are benign, they are the most common presenting symptom in patients diagnosed with breast cancer. A palpable mass in a woman’s breast requires a prompt evaluation. Correct diagnosis of a breast mass is essential for optimal treatment planning, with the primary aim being to confirm or exclude cancer. Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women of all races, and it is the leading cause of cancer death among Hispanic women and second among white, black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and American Indian/Alaska Native women. The triple test (TT) advices the evaluation of palpable breast masses by physical examination, mammography, and fine-needle aspiration (FNAC), and it has proven to be a reliable and accurate tool due to its technical simplicity and reduced expense and morbidity compared with open surgical biopsy. Low-income African-American women often report lower receipt of medical risk information, and due to lack of insurance they do not have a regular source of care, which in turn leads to decreased utilization of medical health services. This case highlights the importance of the utilization of the triple test when evaluating young females complaining of breast masses, but it also emphasizes the important role that providers play when working with underserved populations.

Keywords: African-American; Breast mass; Breast cancer; Underserved populations

Introduction

The most common breast complaint of women presenting to primary care offices is a breast mass, which is reported to be approximately 42 percent [1]. Most breast masses are benign; however, they are the most common breast symptoms of women diagnosed with breast cancer [1]. Patients that present with a complaint of a breast mass need to be evaluated with a detailed clinical history and physical examination to help determine the degree of suspicion for malignant disease and proper work-up, particularly for those who are younger than 40 years of age [1-5]. We report a case of a 37-yearold uninsured African American female who presented to the clinic complaining of a right breast mass, and that through appropriate work-up and referrals was diagnosed and treated for breast cancer.

Case Report

N.S. is a 37-year-old uninsured African American female who presented to the clinic complaining of a right breast lump that had been present for a month. N.S. was seen at the clinic by the Family Nurse Practitioner. During the interview, N.S. described the lump as intermittent, which at times it is not palpable. Reported on and off tenderness to area. Denied nipple discharge or changes in skin. Denied warmth or redness to area. N.S. past medical history includes: hypertension, anemia and asthma. Gynecological history: last Pap smear (06/12/15)–Normal. Menarche: 12 years old. Regular Menstrual cycles. Family history: father–hypertension, mother– hypertension, paternal aunt–breast cancer w/ bilateral mastectomy at age 50. Social history: Single, 2 sons (alive and healthy), not sexually active. Denies smoking, substance abuse, or ETOH. Allergies: NKDA. Surgical history: BTL 2004. N.S. medications include: Lisinopril 10 mg QD, HCTZ 25 mg QD, Singulair 10 mg QD, Proventil HFA, 2 puffs PRN Q4-6 h.

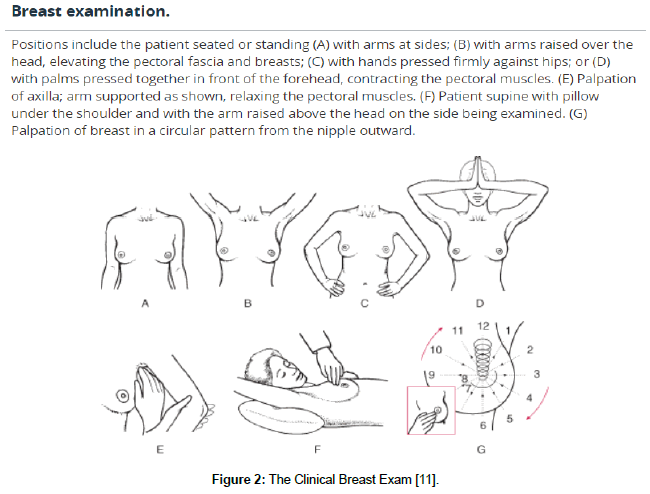

After obtaining a detailed history, a breast examination was conducted. N.S. is a large breasted female, therefore, it was important to conduct a thorough clinical breast exam. Breasts were examined first while N.S. was sitting down and with hands on her hips, then above her head and lastly by leaning over. Then N.S. was asked to lie down, and put her arm behind her head. Each breast was palpated up and down in its entirety. No masses were felt in this manner. N.S. was asked to rotate slightly to the right, and both breasts were examined in this matter. No masses felt. Then she was asked to rotate slightly to the left, and again both breasts were examined. This time, a mass was palpated on her right breast at 9 o’clock. It was approx. 3 cm in size, round, soft, movable and slightly tender to touch. Initial impression, possibly benign breast lesion due to age and health history. Only contributing risk factors are obesity (BMI 31.0) and 2nd degree relative with breast cancer.

As a result of N.S. having no insurance, she was referred to local imaging center that provides low-cost and in many cases free imaging for those that qualify based on income. Order was sent for a diagnostic mammogram with ultrasound if needed, for which patient was assisted with scheduling ASAP. The mammogram and ultrasound confirmed the mass, and because of the degree of suspicion, a biopsy with the use of a fine needle aspiration was recommended by radiologist. N.S. was informed of the findings, and of the urgency to proceed with the biopsy. N.S. at first was upset and stated that she would like to be referred somewhere else before proceeding with the biopsy. It was explained to her that other referrals could take weeks to months, and also that the places where she can be sent are limited as a result of her having no insurance. Therefore, it was imperative to proceed with biopsy to formulate diagnosis and treatment. N.S. was understanding and agreed with plan. The biopsy was conducted, and the radiologist called with the results. The diagnosis was: Ductal Invasive Mammary Carcinoma, grade 3.

Due to the diagnosis, it was highly important to refer N.S. to Oncologist as soon as possible. During this period of time, N.S. experienced a lot of uncertainty and anxiety because of several factors, such as: young age, race, and socioeconomic status. N.S. expressed that there was no way for her to afford consultations, nonetheless treatment with a specialist. Through this process, her PCP (Family Nurse Practitioner) continue to encourage and support N.S. Several days were utilized doing research in order to help N.S. financially and get her set up with Oncologist. Family Nurse Practitioner came across information indicating that Medicaid has a program which provides assistance to low-income women diagnosed with breast and cervical cancer. N.S. was set up with a service coordinator for the program, and she was able to qualify for the program and referred to Oncologist to start treatment.

Discussion

About 1 in 8 U.S. women, approximately 12.4%, will develop invasive breast cancer over the course of her lifetime. In women under 45, breast cancer tends to be more common in African- American women than white women [6]. Overall, African-American women are more likely to die of breast cancer. For Asian, Hispanic, and Native-American women, the risk of developing and dying from breast cancer is much lower [6]. Underserved women, which includes both racial/ethnic minorities and the poor tend to have a greater chance of dying from breast cancer [7]. Underserved women are less likely to seek medical attention as a result of lack of access to health care influenced by having no insurance and high out of pocket costs. This in turn results in later stage diagnosis of disease and decreased survival rates [7].

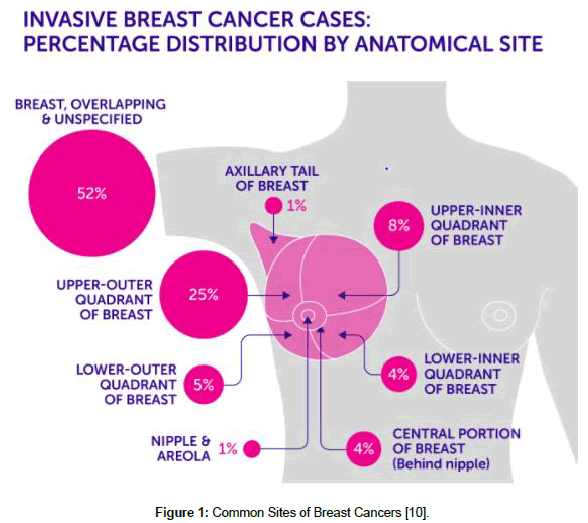

Timely evaluation and diagnosis of a breast mass is highly important. The triple test “TT,” was initially described in the mid-1970s, by Johansen C., The TT serves as a guide for the evaluation of palpable breast masses by physical examination (Figures 1 and 2), mammography, and fine needle aspiration (FNA). The TT has proven to be a reliable tool for the accurate diagnosis of palpable breast masses due to its technical simplicity, and has resulted in substantially reduced expense and morbidity compared with open surgical biopsy [2,4]. Due to the reduced sensitivity and specificity of lesion detection by mammography in young women under 40, the usefulness of sonography in this group of patients has lead researchers to recommend that for evaluation of breast masses in women under 40, for which combined sonography with mammography needs to be used. This is known as the modified triple test score “TTS”, which is an integration of clinical breast examination, sonography and FNA [2,4]. The TTS reliably guides the evaluation and treatment of breast lesions. Lesions scoring 3 or 4 are always benign. Lesions with scores ≥ 6 are malignant and should be treated accordingly. Confirmatory biopsy is required only for the lesions that receive a TTS of 5 [2,4].

Figure 1: Common Sites of Breast Cancers [10].

Figure 2: The Clinical Breast Exam [11].

Working with underserved populations is challenging for health care providers as the resources for appropriate referrals are lacking nationally [7]. For instance, there are currently very few free or low-cost breast cancer screening services available to low income and uninsured women [7]. The National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program (NBCCEDP), provides breast and cervical cancer screening in all 50 states to low-income uninsured and underinsured women ages 40-64. However, there is currently no funding available for those that need mammography at age younger than 40 due to strong family history of breast cancer or complaints of a breast mass [8].

Low-income African-American women often report lower receipt of medical risk information and health advice from providers than higher income and nonminority women [5]. An important predictor of health care utilization services, other than insurance and a regular source of care, is having a provider recommend the test to patients [5]. Therefore, it is possible, that the lower use of health care services by low-income African-American women is a result of deficits in the patient–provider relationship. A strong patient–provider relationship is critical as it plays a big role with patient compliance and adherence to treatment, and more so with underserved populations [5].

Appropriate management of terminal illnesses such as breast cancer can be a daunting task for primary health care providers who work with underserved populations. Much time and knowledge is needed to find ways to help these patients get some financial assistance in order to get the treatment needed. In 2000, Congress passed the Breast and Cervical Cancer Prevention and Treatment Act, which allowed states to offer women who are diagnosed with cancer to access treatment through Medicaid in all 50 states and the District of Columbia [9]. Certain eligibility criteria must be met which can be different by state, however, once enrolled coverage includes: full Medicaid coverage beginning on the day after the date of diagnosis (services are not limited to the treatment of breast and cervical cancer); Medicaid eligibility continues as long as the Medicaid Treatment provider certifies that the woman requires active treatment for breast or cervical cancer; should a woman have a recurrent breast or cervical cancer, the BCCS contractor must reapply for the woman to be eligible for Medicaid [10,11].

This case highlights the importance of appropriate selection of diagnostic tools for the evaluation of breast masses in women younger than 40. The TTS can reliably guide the evaluation and treatment of breast lumps as it allows health care providers to avoid unnecessary open biopsy and to proceed to definitive therapy if a malignant breast lump is present [2]. It also highlights the important role that health care providers, in this case the Family Nurse Practitioner, play in serving as advocates for underserved patients by helping navigate and find resources for appropriate treatment.

References

- Salzman B, Fleegle S, Tully AS (2012) Common breast problems. Am Fam Physician 86: 343-349.

- Khoda L, Kapa B, Singh KG, Gojendra T, Singh LR, et al. (2015) Evaluation of modified triple test (clinical breast examination ultrasonography, fine- needle aspiration cytology) in the diagnosis of palpable breast lumps. J Medical Society 29: 26-30.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) Cancer among women.

- Kachewar SS, Dongre SD (2015) Role of triple test score in the evaluation of palpable breast lump. Indian Journal of Medical & Pediatric Oncology 36: 123-127.

- O'Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J (2004) The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income african-american women. Prev Med 38: 777-785.

- Breastcancer.org (2018) U.S. breast cancer statistics.

- Palmer R, Samson R, Batra A, Triantis M, Mullan I (2011) Breast cancer screening practices of safety net clinics: results of a needs assessment study. BMC Women's Health 11: 9.

- Levy A, Bruen B, Ku L (2012) Health care reform and women's insurance coverage for breast and cervical cancer screening. Preventing Chronic Disease 9: 1-10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2017) National breast and cervical cancer early detection program (NBCCEDP).

- Cancer Research UK (2017) Breast cancer incidence.

- Kosir MA (2018) Evaluation of breast disorders. Merck Manual Professional Version.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi