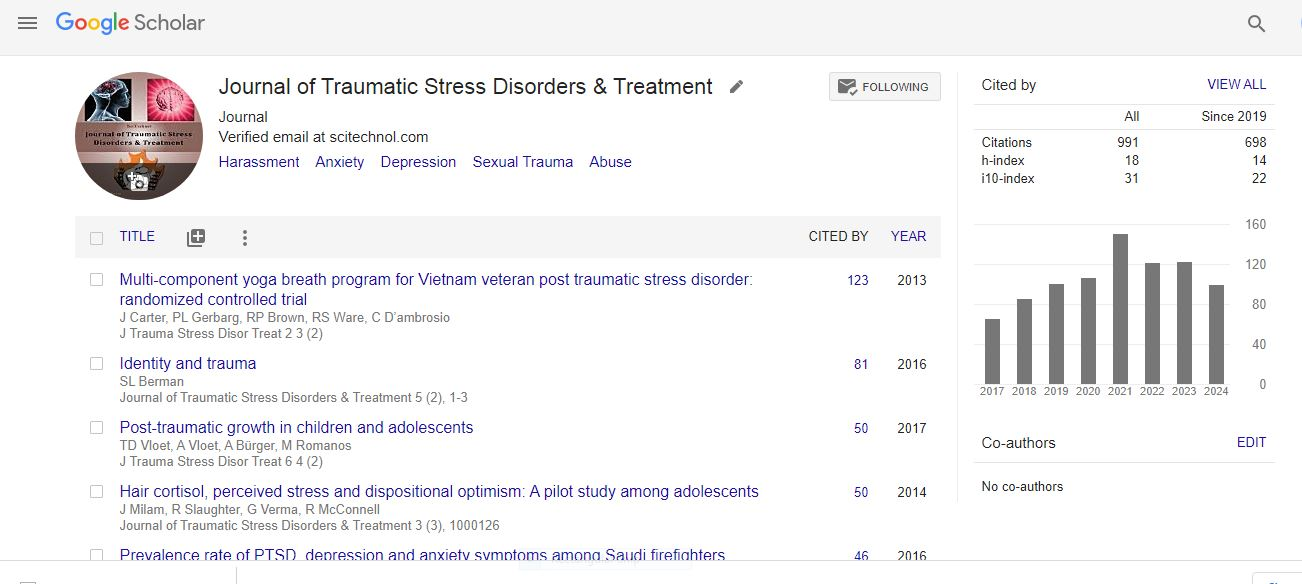

Research Article, J Trauma Stress Disor Treat Vol: 4 Issue: 4

Countertransference in Trauma Therapy

| Anna Cavanagh1, Elizabeth Wiese-Batista2*, Christian Lachal3,Thierry Baubet4 and Marie Rose Moro5 | |

| 1School of Psychology, University of Wollongong, Australia. Alumna of the Liberal Arts and Sciences Bachelor Program, University College Roosevelt,Utrecht University, Middelburg, The Netherlands | |

| 2Associate Professor of Psychology, Social Sciences Department, University College Roosevelt, Utrecht University, Middelburg, The Netherlands. | |

| 3Psychiatrist, Clermont-Ferrant, France. | |

| 4Professor of Psychiatry University of Paris 13, director of the Maison des Adolescents de l’hôpital Avicenne, Paris, France | |

| 5Professor of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, University Paris Descartes. Director of the Maison des Adolescents de Cochin, Maison de Solenn (APHP), Paris, France | |

| Corresponding author : Elizabeth Wiese-Batista Associate Professor of Psychology, Social Sciences Department, University College Roosevelt, International Honors College of Utrecht University, Middelburg, The Netherlands Tel: +31 6 13 93 74 74 E-mail: e.wiese@ucr.nl |

|

| Received: March 13, 2015 Accepted: December 22, 2015 Published: December 28, 2015 | |

| Citation: Cavanagh A, Wiese-Batista E, Lachal C, Baubet T, Moro MR (2015) Countertransference in Trauma Therapy. J Trauma Stress Disor Treat 4:4. doi:10.4172/2324-8947.1000149 |

Abstract

Countertransference in Trauma Therapy

Background: Trauma is perceived as a highly subjective experience depending on personal resources and resilience. The therapeutic relationship in trauma psychotherapy seems to be a special one due to the powerful, emotional charged process of revealing and working with memories of traumatic experiences. This qualitative study explored the countertransference in trauma therapy by means of applying a special protocol in interviewing therapists from various cultural backgrounds.

Methods: Seven trauma therapists were interviewed following a specific in-depth protocol where the method of emergent scenarios was applied. In this method, the therapist describes a client’s traumatic event, thereby triggering various countertransference responses, which are registered and analysed in clusters.

Results: Participants indicated the exceptional use of defence mechanisms, such as minimisation of the clients’ traumatic stories and the presence of reactions such as: affective disconnection, absorption by the scene, use of metaphors, being invaded by the scene, identification with specific feelings, blank-out, confusion of feelings, dreaming and emergent scenario’s appearance. The findings indicated that therapists, who have experienced trauma in their life course and/or genealogy, showed stronger countertransference emotions and reactions. Therapists who did not experience trauma and who were still in the beginning of their career, showed relatively low emotional and physical countertransference responses. The therapists indicated the application of self-healing and other coping strategies to deal with the countertransference feelings and reactions.

Conclusions: The vivid descriptions of the participants gave deep insights into and highlighted the specificity of the therapeutic relationship in trauma therapy. This was presented in the stories of the therapists, which reflected personal aspects of their life experiences. Several participants mentioned silence surrounding personal trauma posed major challenges in trauma therapy. Moreover, the therapists indicated several measures to deal with countertransference issues, such as supervision, specialization and support.

Keywords: Therapist; Psychotherapy; Trauma therapy; Countertransference; Post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSD; Emergent scenario; Therapy

Keywords |

|

| Therapist; Psychotherapy; Trauma therapy; Countertransference; Post-traumatic stress disorder; PTSD; Emergent scenario; Therapy | |

Introduction |

|

| The effects of psychotherapy focusing on the impact of the process on the client’s life have been researched since long [1-3] but the influence of the therapeutic process on the therapist, that, specially in trauma therapy, is of great importance for the therapeutic relationship, has been less investigated. In essence, therapy implies a singular, close, and professional client/therapist relationship, which is based on the input and commitment of both parties. Goldsmith et al. [4] indicated that the therapist’s “thorough understanding of trauma, its effects, and its potential to influence treatment dynamics is essential to the therapy of trauma victims” (p. 457). The therapeutic process also implies the therapist’s reflection of the client’s discourse in relation to its social and symbolic context [5,6]. Through the therapeutic process the identity, values, concepts and belief systems of client and therapist, may therefore be challenged, affected and even altered. | |

| In the specific case of trauma psychotherapy, great challenges are posed, making it more important for the therapist to develop strong support systems and to cultivate self-care strategies. The trauma therapist needs to be very aware of his/her feelings and beliefs to be able to efficiently assist the client. Therefore it is of interest to study the effect of trauma psychotherapy on the therapist - the countertransference process. The focus of this research was to investigate that process, exploring the therapist’s feelings and reactions to traumatic stories. This study has been conducted as a cooperation project between Dr. Wiese, from the University College Roosevelt, in the Netherlands, Prof. Dr. Lachal, and Prof. Dr. Baubet and Prof. Dr. Moro from the University of Paris, in France. | |

| Countertransference in trauma therapy | |

| Countertransference refers to the totality of (unconscious) reactions of the therapist to the client and to the clients’ transference in therapy [7]. Through that concept, the focus is shifted from the client onto the therapist and his/her powerful feelings, which can arise in working with different clients. The countertransference responses are dependent on the therapist’s resources to discriminate well between her/his feelings towards the client that were directly related to the client’s projections, and other feelings with external sources. An accurate discrimination of the different therapist’s countertransference feelings requires the professional ability to make interpretations that are based on the recognition of her/his emotional state [8]. | |

| Countertransference responses function as a primary instrument for analysing the client’s conflicts, as well as the therapist’s own conflicts. Lachal [9,10] discussed this concept further by emphasising specially the trauma therapists’ emotions, cognitions and representations. Countertransference responses can vary from physical/physiological ones, such as fast heartbeat, agitation or in attention, to emotional ones, such as sadness, and strong positive or negative feelings towards the client. They also include cognitive strategies and other reactions as detachment, depersonalization [11]. This wide spectrum of responses describes the therapist’s experience with a certain client, which occur in unconscious and conscious processes, relating to the therapist’s own experiences. | |

| There are several countertransference difficulties that can especifically arise in trauma therapy. Clients who show posttraumatic stress reactions, such as re-experiencing aspects of the trauma and emotional numbing, have often experienced a conspiracy of silence surrounding the traumatic events [12]. There is often silence after a trauma has happened, as the environment tends to deny the occurrence and/or the intensity of the event. When the client starts the therapeutic process, it is the task of the clinician to break this silence in a careful manner, but the disclosure of the trauma can evoke various strong emotions and reactions also in the therapist. | |

| Several countertransference themes re-occur in the therapy of traumatized clients. The therapist needs to be able to provide means for the client to express his/her feelings related to the traumatic experiences, supporting the development of positive coping strategies [13]. Often the client’s traumatic experiences bring dread and horror, grief and mourning. Therapists might feel a sense of bond to the client when s/he recognises familiar aspects of the trauma story that can be related to her/him. Rage is one of the most difficult countertransference reactions to deal with, as it can distract the therapist from the treatment process and hinder him/her to think rationally. Shame and similar emotions are also typical countertransference reactions For instance, clinicians may be ashamed of the disgust they feel when listening to the trauma stories and how the world can be unfair [12]. | |

| Not all therapists are able to deal well with these strong countertransference reactions and emotions. Many apply defence mechanisms to counterbalance the reactions’ effects. For example, some therapists numb themselves by having having an affective disconnection towards the emotional aspects of the trauma stories. Others report mental distancing as a strategy to cognitively deal with the traumatic event description. Furthermore, turning off is used by some clinicians as coping method. Therapists also reported to banalize, convincing themselves that the client is exaggerating in his/her depiction of the trauma, or to minimize the dimension of the traumatic experience. Intellectualisation or rationalisation can also occur, in which the clinician theorises and lectures the patient, hiding behind theoretical explanations, while denying the reality of the trauma [12]. | |

| Although the application of more primitive defence mechanisms appears to be understandable and humane, they can damage the client and inflict a secondary traumatisation. Therefore, it is highly important that clinicians are aware of their coping strategies and the way they use them. Wilson and Lindy [11] postulated the concept of empathic strain, which can develop when clinicians feel overwhelmed with the countertransference and affective reactions in treating clients with PTSD. They defined two major types of countertransference reactions: Type I consists of avoidant reactions, and can include various defence mechanisms, such as denial, minimization, distortion of the traumatic event or emotional withdrawal and detachment. On the contrary, Type II includes over-identification reactions, which can lead to defence strategies, such as dependency on the client, over-commitment, and overemphasis on the traumatic event or enmeshment with the client. The same authors suggested that either Type I or II countertransference reactions can disrupt empathic responses towards the client and his/her traumatic story. As a result, empathic strain may occur, damaging the therapeutic alliance. The authors also hint to the importance of integrating countertransference reactions into trauma therapy and to be aware that some affective responses may be directed towards the traumatic material and not to the client per se. To normalise and expect countertransference reactions can help the therapist to sustain an empathic relationship with the client, which return creates a safe-holding and a stable environment for the therapy process. | |

| The experience and age of the therapist seem to highly influence the countertransference responses in trauma therapy [14,15]. Cushway [14] found that trainee therapists experience higher level of distress than their older, more experienced counterparts. Younger therapists, who are still in training or just finished it, however, are less likely to display weaknesses; they might feel guilt and shame about their strong countertransference reactions and are less likely to report it in supervision [15]. | |

| Allmark et al. [16] pointed the importance of ongoing education and constant individual and group support for trauma therapists, emphasizing the relevance of organizational policies to make sure that these procedures are established. This support can, for example, be provided to the trauma therapist by a multidisciplinary team [17,18]. | |

Methods |

|

| The aim of this qualitative study was to investigate the therapists’ countertransference responses in trauma therapy, being trauma therapists interviewed about their experiences and feelings in therapy. Additionally, it was explored how the therapists’ traumatic experiences, either in their own life or genealogy, influenced these responses. | |

| The sample obtained for this study included 7 trauma therapists, 4 men and 3 women, from various countries and backgrounds, with ages varying from 27 to 74. At the time of the interviews the participants’ practiced trauma therapy in Croatia, Germany, the Netherlands, and United States of America. The therapists were approached due to their expertise in the field and their willingness to participate in the project. Five participants were interviewed while attending an expert meeting about trauma therapy, while two other participants were interviewed at their workplace. All participants signed an informed consent for research, being ensured of confidentiality and anonymity. The interviews lasted 50 to 120 minutes, being conducted by two different interviewers. Four of the interviews were conducted in English, one in French and two in German. All interviews were recorded and later on transcribed in English. By the use of two trained interviewers the saturation of the research prevented was avoided. | |

| The instrument used for this qualitative study included a semistructured interview protocol, developed by Lachal et al. [19], that was specifically designed to assess the countertransference reactions of therapists in trauma therapy. This protocol includes an original way of investigating countertransference [7], which involves the description of an emergent scenario that depicts what happens to the therapist in relation to the client and the traumatic experience. The aim of evoking the emergent scenario is the investigation of physical, cognitive and emotional countertransference responses of the therapist to the client and the traumatic material. In this emergent scenario technique the therapist is firstly asked to describe a traumatic event that a client has told him/her in therapy, and after this description the therapist indicates the emotions that experience has provoked in him. Through this technique unconscious aspects of the therapist’s countertransference can be made conscious, and be registered in the interview protocol. | |

| The interview protocol (see Appendix A for detail) is divided into several sections with the following themes: The therapist’s trajectory (country of origin, mother language, age, religion, professional background and traumatic genealogy); whether s/he believes that parts of the clients’ trauma could be transmitted onto her/him; whether s/ he thought of needing to protect her/himself from potential trauma transmission; the trauma and personal history and the exploration of the countertransference with the traumatised client (using the emergent scenario). The last part of the interview protocol, in relation to the emergent scenario described by the lists, forty different emotional reactions such as hostility, rage, tension, excitement and other. The therapist is asked to rate, on a quantitative intensity scale ranging from 0 to 5, each emotional reaction provoked by the emergent scenario s/he has described. Furthermore, s/he is asked to indicate the intensity (0-5) to which s/he experienced physical reactions, such as tiredness, headache, agitation and other. Additionally, s/he has to specify whether cognitive countertransference reactions were experienced. For example, whether s/he has minimised or affectively disconnected from the traumatic story and whether s/he felt absorbed by the client’s explanation of the scenario. Moreover, the therapist has to indicate whether s/he has ever felt invaded by images or scenarios that the clients revealed to her/him, or whether s/he has ever experienced a mental blank out. | |

| After detailed transcription of the interviews a thorough content analysis of the selected material was carried out. Information was clustered into meaningful units and organised around themes and sub-themes. For example the theme of trauma concepts includes various sub-themes, such as the subjectivity of trauma, the specificity of the therapeutic relationship, and trauma transmission and protection. The results of the potential traumatic experiences in the genealogy and life story of the therapists were summarised and further elaborated on. Direct quotations of participants were used in the results section to maintain the originality of the therapists’ answers and to increase the validity of the outcomes. | |

| From the 40 different emotional countertransference reactions proposed by the protocol, 5 were taken out of the analysis: hindrance/ disagreement, craziness, feelings of being outmoded, immobilised/ hypotonic and anguish, as they proofed irrelevant to the analysis or were already accounted for by other emotions. Some reactions, such as the wish to stop the consultation or the interaction, were combined into one. This translated into a total of 33 emotional reactions, which were clustered as follows: Guilt emotions - guilt, shame; Hostile emotions - hostility, fury, revenge; Aversive emotions - injustice, annoyance; Doubt emotions - doubt, distrust, displeasure; Sad emotions - fear, panic, sadness, fell like crying, very serious, very affected, horror; Passive emotions - impotence, indifference, passivity; Constructive emotions - admiration, excitement/joy, surprise, calm, very familiar, very confident; Emotions affecting the therapeutic relationship - difficulties to concentrate, contradictories feelings, tension, avoiding the contact, lack of efficacy in the consultation, having fear patient acts out or commits suicide, wish to stop consultation/interaction. | |

| The score for each emotional reaction in one cluster was added and then divided by the number of its total components to achieve an average score. As mentioned previously, the intensity scale ranged from 0-5 indicating: 0-1: low; 2-3: moderate; 4-5: high emotional countertransference reactions. The 10 different physical reactions and the various cognitive countertransference responses were evaluated individually in accordance to the participants’ answers. | |

Results |

|

| The interviews generated a great variety of responses, which were organised under certain themes and sub-themes with the aim of answering the research question of how therapists deal with trauma therapy and their countertransference reactions. The first presented theme refers to the therapists’ opinions about trauma and its concepts, followed by the second theme that relates to the trauma and personal history of the participants. Lastly, the therapists’ countertransference reactions are presented. | |

Therapists’ Concepts about Trauma |

|

| Trauma transmission and protection | |

| The therapist’s points of view about whether trauma could be transmitted and whether one had to protect her/himself differed. Five (in seven) therapists agreed that trauma transmission was possible, and that it was very important to prepare oneself, such as to have specialized education and supervision. One said, for example: “the women in ….. (country’s name) had terrible stories about the way they have been tortured. The supervision helped.” Another therapist pointed out that trauma could be transmitted onto the clinician; however it had not happened to himself. The reason for this, he continued, was his alertness, and awareness of not getting too involved with the traumatic material. A different therapist described: “I think you can have images and nightmares, but it would never reach the same intensity". | |

| One less experienced therapist denied that trauma could be transmitted. She further indicated that she did not have the feeling that she needed to protect herself from the traumatic material of the patient. Another clinician also did not believe he was in need of self-protection. He rather was of the opinion that he needed to be absorbed by the trauma: “I don’t think I can help people without immersing myself in their experiences.” | |

| Some participants mentioned self-protection strategies, such as specialization, and supervision but also distancing oneself. One clinician pointed out: “I have colleagues with whom I can share and I think this is a very essential thing. It is not good to do this sort of work on your own (…) to have some sort of regular feedback, to ventilate some feelings, to have case discussions is very supportive.” | |

| Therapists’ trauma and personal history | |

| This section is about the therapists’ personal history and experiences. Each participant was asked about traumatic experiences in her/his genealogy, as well in her/his life course and how s/he was affected by these experiences. Additionally, his/her opinion whether traumatic experiences influence the behavior and or the efficiency of the therapist was asked. Some of the main findings are summarised in Table 1 below. The participants in this and the next section are referred to as participants 1 to 7 (P1 to P7). | |

| Table 1: Summary of the Therapist’s Trauma and Personal History. | |

| Therapist’s genealogy | |

| As can be seen in Table 1 the majority of the therapists experienced trauma in their genealogy and life course. Notable is that the two young therapists (P6 and P7), from Germany, did not know about traumatic events in their family history, even considering the occurrence of the Second World War - WWII. One explained to the question about possible trauma in her genealogy: “No, not that I know of…well maybe my grandparents. My grandpa was in the war but I don’t know what he experienced there. I’m sure he experienced horrible stuff there but I don’t know anything about it…” Another clinician (P5), substantiates that theme by indicating that his traumatic experience consisted of a transmission of silence, as he stated: “Well, what I recognised is that there is a culture of transmitting silence or trying to protect the new generation by not telling much about the past. At a certain time in my age, in adolescence, I started to ask questions. Then my parents started to tell me things.” | |

| Three participants mentioned the WWII as a traumatic life event in their genealogy, which also had direct consequences in the way they felt in their own lives. One subject (P1), for example, was of Jewish background and had lost many family members through that war. He reported: “My parents were concerned that maybe I have been traumatized, after all because of my traumatized mother.” He further stated that the generation of his grandparents “tried hard to negate their traumatic past, and the next generation, the generation of my parents, grew up with a major trauma in America. So, it was in this context that I was raised.” | |

| Therapist’s trauma history and effect | |

| Table 1 shows that five out of seven participants had traumatic experiences in their life course. One psychotherapist (P1) reported to have been traumatised by witnessing his father’s death when he was six years old. He further explained that: “in reflection about that summer, the atom bomb was dropped, the first pictures of the holocaust came and my father died, and in my development those three events…ah…became fused. In that, all three were events that the older generation couldn’t explain. So suddenly I was…the world was a very different place.” | |

| Another therapist (P3) mentioned direct war experience as being traumatic: “The most traumatic thing could be the bombardments.” Other experiences had also a profound effect on the subject as he further mentioned: “I had other difficulties, of course, about being gay, and of having to accept that I am gay, it was not very easy.” | |

| A different subject (P2) described his traumatic experience as follows: “I had transmission of war. I had relatives in the WWII and stuff that happened there with the family. And also war-time in Croatia. Many stories of war and survival of war and confiscation of properties, from my family and the right in this socialist, communist system... There was a double morality, a double standard. You had to split very easily.” Two therapists (P6 and P7) reported to not having experienced a trauma in their life. | |

| Therapist’s efficiency | |

| Independently of their previous answers, the therapists were asked to indicate whether they thought that the fact that a therapist experienced a traumatic event could change her/his behaviour and efficiency as therapist. One clinician (P4) indicated that therapists “must be aware of that trauma and of the blind spot, especially with traumatised patients.” This is in alignment with the view of another subject (P7): “Well, I think it depends how the person has dealt with the trauma… I think there’s no general answer.” One of the therapists (P7) thought that a personal trauma history influences the therapist, depending on the trauma: “Yes, I think it can. I mean not with accidents or something like that. But with something like sexual abuse I can hardly imagine it...I think it triggers such intensive feelings in you even when you hadn’t experienced abuse yourself.” Another therapist (P5) indicated the importance for the therapist of being sensitive and take into account how much a client can afford in a certain phase of the therapeutic process, pointing that this sensitivity can be even better developed when the therapist had traumatic experiences her/ himself. | |

| Two other participants thought that having experienced a trauma can have some positive effects, such as one (P3) stated: “… it has given me some sympathy for the survivors of violence … of war.” Another subject (P1) explained that traumatic experiences are beneficial and almost necessary: “I would say that for myself and my colleagues…if there is not experience with some kind of traumatic experience in their life or in their past, they are not very good. (…) If we can’t draw that connection in our own lives, in some small way, never quite know what our patient experienced.” | |

| Therapists’ countertransference reactions | |

| This section explores the countertransference reactions of the participants in more detail. Firstly, each subject (P 1 to P7) was stimulated to remember the description of a situation, told to her/him by a client in therapy about a traumatic experience. Following the therapist was asked to make a brief description-emergent scenario of the situation. After this narrative, a list of possible reactions and emotions was shown to the therapist and s/he indicated the correspondent countertransference reactions on an intensity scale from one (low) to five (high). Additionally, s/he had to specify cognitive aspects of the countertransference. | |

| The therapists described a variety of emergent scenarios, in which patients revealed their traumatising experience (see Table 2). A rather complex situation was presented by a therapist (P1), who worked with a war veteran: “So the case is of a veteran…with all the classic symptoms, and particular problems with aggression; he likes to shout at his wife (…) He has a dream in the treatment… in which he identifies a nurse as an enemy, and he singles out his rifle to kill the medical support person on the other side. Then immediately the transference is that, I’m in a position of going to help him, I’m in danger of my life… And then the countertransference: gradually he takes me to an Israeli mission in the session; he comes upon a village, he is the person in charge, there are no men in the village, there is movement…and he decides to open the fire…and there is a massacre.” The therapist (who has a Jewish background) explained that he was quite affected by the description of the event: “So…following the session, I meet a colleague, and I begin to talk about this, and I say that I’m supposed to be empathic with him, but I want to kill him…ah…He calls me at the time of the next session, he is drunk, he wants medication and I develop a severe headache. As it happens, I say to myself: ‘This could kill me; this headache could kill me.’ And later, I have an additional thought that perhaps it is my internalising, my wish to kill him, that I didn’t want to be part of it. So then, then over a period of weeks, I go through a series of countertransference reactions, that I gradually become aware of.” | |

| Table 2: Summary of the Therapist’s Emotional Countertransference Reactions. | |

| Another psychotherapist (P2) also described the situation of a veteran: “The Dutch corps has been in Slovenia as part of the peace UN forces. And he (the client) was there in the army witnessing all sorts of things and was not being able to help the Bosnians because of their position of not actually taking a party. The mission was designed as being neutral while it is of course very difficult to be neutral while watching the perpetrator commit all these crimes on the victims. First of all the guy had a lot of problems watching on one hand the Serbians committing all these crimes on Bosnians. On the other hand he had a lot of problems with the Bosnians themselves who were stealing things from the UN camp, who were coming and offering their daughters to the UN soldiers for money, for prostitution…so this very blurred vision of who is the victim and who is the perpetrator and with whom can I identify.” | |

| A different subject (P3) mentioned a client who told him about witnessing the deadly accident of his brother: “I have the situation of a young man, who was on a Saturday on a sailing boat in one of the rivers in Holland, with his brother and his sister’s fiancé. And…all of the sudden his brother dropped over board, and…the current was so strong that…although he could swim, he could not reach the boat anymore. Then, my patient, he dropped into the water, in order to save his brother. And he was swimming to his brother and…he could reach him but he could not keep his head long enough above the water, so the brother has drowned and he himself thought that he was drowning too, because he couldn’t reach the boat. And then, the boat was able to…the people in the boat were able to stir the boat a bit and they could reach him and he was saved. But his brother has drowned in front of his eyes. Of course he was affected by this fact very much and…but the most important reaction for him was that he could not bring this in line with his strict Calvinist origin. So he…he was completely, how to say, he…he lost his… the world had changed... And for many months he was sick at home …he couldn’t sleep at all and he had dreams about the situation. And then after 1 ½ yeas he was sent to me (…).” | |

| Other situations referred to war experiences, such as one clinician (P4) explained: “There was a woman from a Bosnian concentration camp. She was raped and tortured by soldiers who were her neighbours from the same village.” And another therapist (P5) has mentioned “a very traumatized young client that reported being raped during the war in her country while she was 7 months pregnant.” | |

| One situation was related to domestic violence as one clinician (P6) described: “there was one patient who told me that her ex-husband had chased her through the apartment and she opened the window to call for help. And then he got her and held her out of the window. And … she was really scared to die because she thought he would effectively throw her out of the window.” Another psychotherapist (P7) described the traumatic event of child abuse: “Well, there was this client who told me her story. On her 7th birthday she was raped by her neighbour in a very torturous way...” | |

| Emotional countertransference reactions | |

| The participants showed various emotional countertransference reactions to the previously described events that differed in intensity. The emotional reactions were summarised into eight different categories including guilt emotions, hostility, aversion, sadness, constructiveness, and emotions affecting the therapeutic relationship. The average scores for each category, in correspondence to the described events of the patients, are presented in Table 2 below. The numbers of the participants – P1 to P7 – are related to the sequence in which the events were previously presented. | |

| Table 2 exemplifies the different intensity levels of the therapists’ emotional countertransference reactions. The first subject presented (P1), had overall strong countertransference emotions. He expressed moderate guilt, doubt, sad, passive and constructive emotions in relation to his client’s experiences and behaviour as a soldier. Additionally, he showed high levels of hostile and aversive emotions, as well as strong emotions affecting the therapeutic relationship. | |

| The next participant (P2), expressed no guilt or passive emotions, low levels of hostile and doubt emotions and moderate levels of aversive, sad and constructive emotions, as well as moderate level in emotions affecting the therapeutic relationship in relation to his client’s traumatic experiences as a soldier. Other participants also expressed emotions with a moderate intensity scale, (P3) for instance, experienced moderate aversive emotions, such as feelings of injustice and annoyance, and moderate sad and constructive emotions. The following therapist (P4) showed moderate doubt and sad emotions with an intensity level of 3 to his patient’s event of rape and torture. The affecting the therapeutic relationship was also moderately experienced by him. Another therapist (P5) also referred moderate intensity of countertransference emotions in relation to guilt, aversive and sad emotions as well as emotions affecting the therapeutic relationship while she indicated low level of emotions in relation to hostility, doubt, passive and constructive emotions. | |

| The last two therapists (P6 and P7) showed overall low emotional countertransference reactions. One participant (P6) indicated that she experienced no guilt or passive emotions to the patient’s event of domestic violence, as well as no emotions that can affect the therapeutic relationship, such as tension or the wish to stop the consultation. The other (P7) showed slightly higher countertransference (than P6) by specifying moderate hostile and sad emotions, as well as moderate constructive emotions, such as being calm and confident. | |

| Notable is the total sum of the average on the countertransference emotions, in which the most experienced participants (P1, P2, P3, P4 and P5) have a higher total level, respectively 28, 13, 11.5, 12.5 and 15 while the less experienced participants (P6 and P7) have a lower total level of 5 and 8,5 respectively. | |

| Physical countertransference reactions | |

| The participants also showed a variety of physical countertransference reactions in relation to the described emergent scenario, such as tension in the body, agitation, headaches, the wish to move, to hold or consult the client. Most subjects had overall low physical responses to the emergent scenario. The majority of the therapists, six out of seven, expressed the wish to consult the client. Most subjects (P2, P3, P4, P5 and P7) also expressed the wish to hold or embrace the client as a response to the emergent scenario description. Agitation and body tension were also mentioned as physical countertransference responses by some therapists (P2 and P4). One subject (P1) indicated to have experienced strong headaches during the encounter with the patient. | |

| Cognitive countertransference reactions | |

| The therapists were asked about different cognitive aspects of their countertransference experience in relation to the emergent scenario or other situations. The summary of the trauma therapists reactions is summarizes in Table 3. | |

| Table 3: Summary of the Therapist’s Cognitive Countertransference Reactions. | |

| Each therapist was asked whether s/he had a situation before, in which s/he did not know what to say to the client, having a blank-out. Most participants indicated that they had such an experience. One subject (P4), for example, stated: “Sometimes I have that…that you just out of words because something is so impressive and so powerful and so bizarre…you just do not know what to say about it.” | |

| The participants were also asked about different cognitive strategies that they might have used in response to the traumatic material of their clients. The subjects indicated whether they tried to banalize and to minimize, or affectively disconnect from the traumatic material. Additionally, they specified whether they felt absorbed in a scene that some patients described and whether they were invaded by images, scenarios, deep personal associations or experienced a mental blank out. The results showed that most participants denied banalizing the material described by the clients, and only two of the therapist (P2 and P5) referred to have minimized the traumatic experiences of their clients. P4, however, regarded minimization as a warning sign: “Whenever I feel the urge to minimise I ask myself why I’m feeling that and try to grasp why I do that. Just because I know it’s one of the pitfalls.” | |

| Most therapists indicated to disconnect affectively from the described traumatic experience of the clients, as one subject (P6) stated: “I distance myself as a strategy. For example I tell myself that it is good that the patient is not anymore in that situation … I keep an emotional distance there for myself.” Another subject (P4) also specified to sometimes disconnect affectively from the patient’s trauma. However, he explained the use of the strategy rather critically: “I do that especially with those clients who also disconnect themselves from their story and tell it as it is somebody else’s story.” | |

| Four out of seven participants specified to feel at times absorbed by the scene that her/his client describes. For example, one subject (P4) stated: “Sure that is something that when it happens you just get emerged into that. …” Another subject (P2) explained: “I think to a certain extent you are in the story but not too much. Of course you have to follow the patient a bit, otherwise you can’t help either, and the patient would realise if you would not be involved at all…” | |

| Some clinicians indicated that they have experienced invasive feelings and/or had blank outs in relation to the client’s description of traumatic experiences, such as one subject (P1) described: “I’m always associating, so that I associate very well with an image. The image may or may not have to do virtually with what the patient is talking about. Sometimes I have to search to see what the connection is.” Two clinicians denied the experience of invasive feelings. | |

| Summarizing, the cognitive countertransferences reactions most frequently referred to to by the therapists were: identification with specific feelings, affective disconnection, being invaded by the scene, being absorbed by the scene, using metaphors with the client, having a blank-out, having an emergent scenario coming to the mind, and having dreams about the traumatic experience of the client. | |

Discussion |

|

| This study has generated several findings that may be interpreted in various ways. Interestingly, the participants differed in their opinion whether the clients’ traumatic material could be transmitted onto the therapist and whether they had to protect themselves from their clients’ traumatic material. Most therapists believed that trauma transmission was possible, although it had not happened in practice to all of them. Seemingly, the therapists who had experienced trauma in their life story or genealogy were more likely to think that traumata could be transmitted. Not all agreed, however, whether protection against trauma was necessary. One therapist thought that protection was not needed and that s/he would rather immerse her/himself in the clients’ descriptions of the traumatic experiences in order to sympathise with them. Another therapist, who was less experienced, strictly denied the transmission of trauma or the need for selfprotection. | |

| These differences in opinion expressed by the therapists might be explained by their variation in age, years of practice and professional and cultural background. The age range of the sample was very wide, from 27 to 74 years, reflecting different life and professional experiences. Nevertheless most of the therapists highlighted the importance of several vital supportive strategies, such as professional education and supervision. Furthermore, the significance of collegial support was mentioned and the danger of giving trauma therapy without any support was emphasised. | |

| The findings of this study also indicated vast differences among the therapists in regard to traumatic experiences in their life course and genealogy. The personal experience of trauma appeared to have an effect on the countertransference reactions. This seemed specifically the case when the traumatic experience was in close proximity to the client’s experience. However, as the results of this study pointed out, in the opinion of the participants, it does not necessarily impede the therapist’s efficiency, as long as s/he is able to manage her/his countertransference accordingly. | |

| Some of the differences in opinion and countertransference reactions among the interviewees may also relate to the variation in their cultural background and up-bringing, that most likely influenced their conception of trauma. Parson [20] emphasised that “ethnocultural factors (…) shape common and unique human responses to psychological traumatization. They determine both normal and pathological post-traumatic formations and organize the expression of post-traumatic stress disorder” (p. 221). This underlines the important role that cultural aspects play in the comprehension and treatment of traumatic experiences. The cultural differences of the therapists are also reflected in the wide range of clients that they treat. For instance, three therapists mentioned the trauma treatment of asylum seekers, refugees and war victims, whereas other therapists described their work with victims of sexual abuse, domestic violence or other traumatic experiences. It is most likely that these different dimensions of trauma also had an impact on the therapists’ countertransference reactions and the applied coping mechanisms. | |

| Some participants, who experienced trauma in their life course or family history, had the opinion that these experiences were beneficial to their work as therapists, as they increased their ability to feel empathy for and sympathise with the clients. One participant, furthermore, stated that he would not be a good therapist without having had traumatic experiences himself. Another participant, additionally, mentioned that his personal experience with trauma has functioned as a motivator to become a therapist, as it helped him to recognise what was important for him. These findings are supported by Arnold, Calhoun et al. [21] in their study, as they found that therapists who had traumatic experiences overall define those as beneficial and as learning experiences. | |

| The intensity of countertransference responses of the therapists, who have not experienced traumatic event themselves, seemed lower in comparison to the rest of the interviewees. This might relate to the fact that these participants were also still in the beginning of their career, which may have led to a suppression of strong countertransference responses. Notable, is that the same participants mentioned distancing and affectively disconnecting as cognitive aspects of their countertransference, which may hint to the inhibition of strong emotional responses to the traumatic material of their patients. Pearlman et al. [15] pointed out that trainees often use the strategy of distancing as a response to the anxiety of failing as psychotherapists. The anxiety of failing can be especially high at the beginning of the therapists’ professional experiences, when the professional identity is still being developed and integrated into the self-concept. | |

| Other participants also mentioned the application of some cognitive strategies to cope with their countertransference responses. For instance, one therapist indicated that he had used minimisation of the clients’ traumatic materials in order to cope with them. The same participant, however, stated that he has always challenged the use of minimisation and he has questioned why he applies this specific cognitive strategy. As Wilson and Lindy [11] pointed out, the awareness and critical analysis of certain cognitive strategies in trauma therapy are highly important because they ensure that the countertransference reactions do not affect the therapist’s efficiency and ability to emphasise with the client. Other cognitive strategies, such as identification with specific feelings, affective disconnection, being invaded by the scene, being absorbed by the scene, using metaphors with the client, having a blank-out, having an emergent scenario coming to mind, and having dreams about the traumatic experience of the client all occurred with the majority of the trauma therapist with specific clients. | |

| Notable is that several therapists in this research have mentioned that there was silence surrounding their own personal trauma. They indicated that this silence was often passed onto from one generation to the following, being that more specifically in the case of war trauma. Silence is a special characteristic of trauma as traumatic events are often too horrible or disturbing to be openly discussed by the family and/or the community. Survivors might feel that their surrounding environment is not willing to listen to their experience or they decide to keep themselves quiet about the traumatic experiences as they wish to forget them. | |

| Another reason why trauma often remains unvoiced might relate to protection. In this investigation, one therapist, for instance, stated that his parents wanted to protect him from the trauma by being silent about it. This can, however, have a contradictory effect. Silence can make it more difficult for the traumatised person to cope with the experience as it limits the opportunity to ask for help and to work through it. The findings of this study also have suggested that trauma can be transmitted from one generation onto the next, in a transgenerational mandate, highlighting the far-reaching and continual effect of trauma, which is often underestimated [22]. | |

| Limitations, strengths and suggestions | |

| The small number and the great variation of therapists included in this study, in relation to age, cultural and professional background and life experiences can be considered a limitation. However, the variation in therapists’ age and background provided for a more diverse insight into countertransference reactions. The richness and deepness of the interviews and the descriptions given by the participants resulted in very precious material and contributed to the understanding of the countertransference process in trauma therapy. | |

| The use of an established interview protocol [19] developed by experts in the field, was highly beneficial. The method of emergent scenario, allowed for a vivid and broad presentation of trauma experiences and their characteristics. The emotional account of the client’s traumatic event gave deep insight into her/his position, as well into the role of the therapist. Empathy and understanding can be felt for both parties involved in the therapeutic process. Furthermore, the model of emergent scenario revealed the dynamic interaction between the client and the therapist in trauma therapy. This understanding of and insight into the therapeutic relationship can be highly useful for the analysis of countertransference and may assist therapists in the trauma therapy. The richness of information also highlighted the specificity of emotions that surround trauma therapy, which can function as guidance and support in the training of future therapists. | |

Conclusion |

|

| This study reveals several findings that give insight into the countertransference responses of trauma therapists. Trauma is perceived as a highly subjective experience depending on personal resources and resilience. This can be seen in the individual trauma stories of the therapists, which reflect personal aspects of their life course and/or genealogy. The therapeutic relationship in trauma psychotherapy seems to be a special one due to the powerful, emotional charged processing of the revealed traumatic events. As mentioned previously, this affects the patient, as well as the involved psychotherapist. One of the findings reveals that therapists with a personal trauma history have stronger countertransference reactions in trauma therapy, indicates the importance of applying self-healing and other coping strategies as well as the through analysis of the countertransference emotions and reactions. However, these strategies are also highly beneficial for trainees and less experienced trauma therapists, who may have a tendency to suppress strong emotional reactions. | |

| The interviewed therapists mentioned several important approaches to deal with countertransference in trauma therapy, such as supervision, specialization and support, which demonstrate their knowledge to appropriately deal with emotional reactions. Some participants mentioned the application of defence mechanisms, such as minimisation or distancing. However, most psychotherapists were cautious in the use of such strategies and thoroughly questioned their application. This exemplifies the need of careful analysis of the countertransference reactions, in order to avoid a strain on the therapeutic relationship. | |

| Moreover the findings showed that traumatic experiences can be surrounded by silence both for clients as for therapists. This conspiracy of silence, often maintained by communities and the immediate social context, can be harmful and have long-term effects on trauma survivors. In the worst case, the maintenance and perpetuation of the silence that surrounds trauma can inflict a secondary traumatisation. To break the silence that covers traumatic experiences is one of the main challenges that trauma therapists and clients often face. | |

| Finally, aside from the challenges that trauma therapy can involve, there are several rewarding outcomes that warrant attention. These include the high importance and meaningfulness of helping a large variety of people to recover and restore their lives, and develop their personal growth and strength after having experienced trauma. On a positive note, the statement by Pearlman and Saakvitne [15] sums up some of the deeply enriching experiences that trauma therapy can provide: “Sharing joy and sorrow, laughter and pain, wisdom and ideas with another person is at the heart of what it means to be human. The many moments of such connection in therapy deepen our own humanity” (p. 405). This shows that the challenges of trauma therapy may be transformed into opportunities for increased empathy and personal understanding. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi