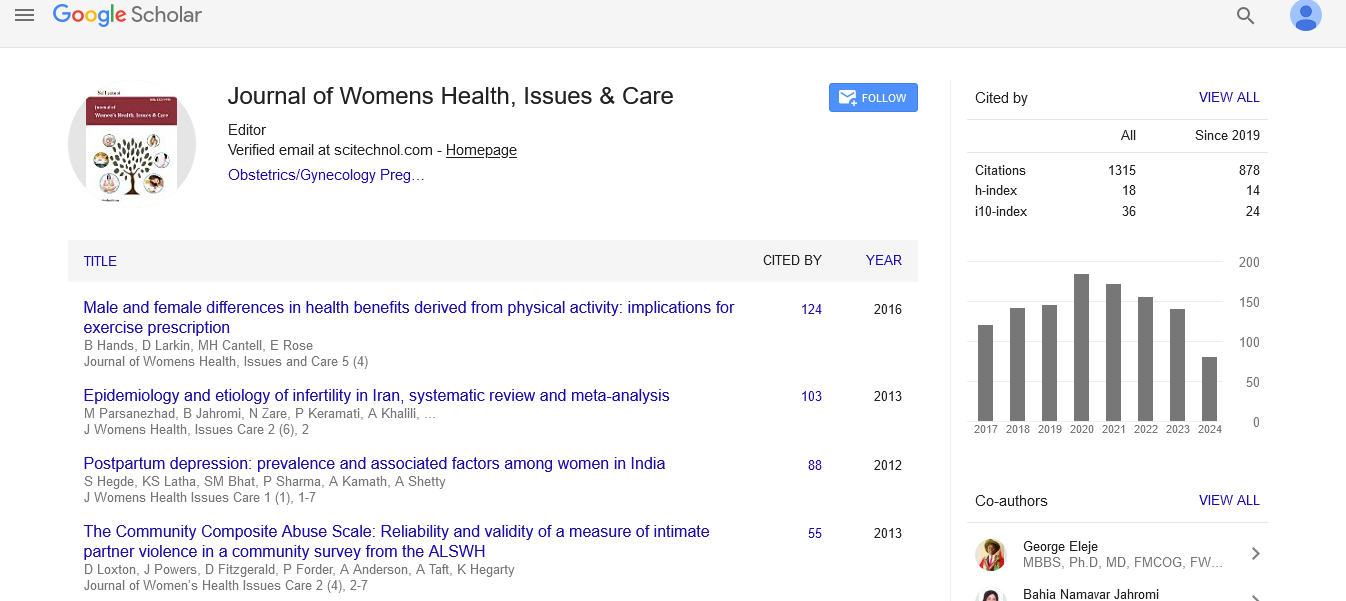

Research Article, J Womens Health Issues Care Vol: 7 Issue: 3

Comorbidities and Risk-Adjusted Maternal Outcomes: A Retrospective Study on Administrative Data

Di Giovanni P1,2, Di Martino G2*, Tonia Garzarella2, Ferdinando Romano3, Tommaso Staniscia2,4

1Department of Pharmacy, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy

2Postgraduate School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy

3Department of Public Health and Infectious Diseases, “La Sapienza” University of Rome, Italy

4Department of Medicine and Aging, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti- Pescara, Chieti, Italy

*Corresponding Author : Giuseppe Di Martino

Postgraduate School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine, “G. d’Annunzio” University of Chieti-Pescara, Chieti, Italy

Tel: +3908713554118

E-mail: peppinodimartino@hotmail.com

Received: April 27, 2018 Accepted: May 10, 2018 Published: May 15, 2018

Citation: Di Giovanni P, Di Martino G, Garzarella T, Romano F, Staniscia T (2018) Comorbidities and Risk-Adjusted Maternal Outcomes: A Retrospective Study on Administrative Data. J Womens Health, Issues Care 7:3. doi: 10.4172/2325-9795.1000309

Abstract

Abstract Objective: The aim of this study was the evaluation of maternal outcomes and of the associated risk factors occurred in Abruzzo region, Italy, from 2009 to 2013. Methods: The study considered all the deliveries performed from 2009 to 2013 in Abruzzo region, Italy. Data were collected from all hospital discharge records. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to calculate crude odds ratios for each comorbidity. Stepwise multiple logistic regression models with backward selection were performed to identify predictors of the most frequent outcomes. Results: 57, 260 deliveries were analyzed. Severe complication occurred in 0.9% of all deliveries. The most frequent complications were “Severe Hemorrhage”, “Hysterectomy”, “Uterine rupture” and “Severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia”. Malignant cancer (OR=55.76), coagulation disorders (OR=37.21), acute pulmonary disease (OR=29.75), placenta previa (OR=26.51), caesarean section (OR=3.24) and age (OR=1.08) were associated with a higher risk of hysterectomy. Anemia (OR=14.64), coagulation disorders (OR=10.31), cardiac disease (OR=12.74), pregnancy hypertension (OR=2.66), major pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (OR=2.78), placenta previa (OR=9.42) and multiple pregnancy (OR=3.69) were associated to severe hemorrhage. Thrombocytopenia (OR=26.04) and diabetes (OR=5.05) were associated to uterine rupture. Overweight or obesity (OR=25.88) and pregnancy cardiovascular disease (OR=25.85) were associated to pre-eclampsia. Conclusions: Maternal comorbidities are associated with increased risk of complications and may result in substantial costs to the health care system.

Keywords: Pregnancy; Delivery; Risk adjustment; Mortality; Stillbirth

Significance

What is already known? It is known that obstetrical outcomes are frequently linked to maternal morbidity, increasing the risk of complications and resulting in substantial costs to the health care system.

What this study adds?

Severe maternal outcomes occurred in about 1 of 100 deliveries. The long observation period and the large database allowed the risk adjustment analyses establishing the risk factors for the main severe maternal outcomes.

Introduction

The Global Health Community has focused attention on reducing maternal mortality and morbidity through a sequence of initiatives as [1,2] “The Safe Motherhood initiative” and “Partnership in Maternal and Newborn and Child Health” [3]. In Italy, such as in other high-income countries, labor and delivery are the leading causes of hospitalization among women aged 30-40 [4]. It is anticipated that 15% of pregnancies will involve complications that require additional medical care [5]. Therefore, a high level of cesarean delivery (CD) performed without medical indication could increase the risk of maternal morbidity [6]. Italy has one of the highest CD rates in the world [7] mainly due to repeated elective cesarean section (CS), and least due to primary CS [8]. Generally, obstetrical outcomes are used as a measure of quality in maternity care and mode of delivery is associated with different maternal outcomes [9]. Moreover, obstetrical outcomes, as indicators of maternal morbidity, could be used to improve maternal care quality basing on a large body of data [910]. In any setting, women who develop severe acute morbidity during pregnancy share many pathological and circumstantial factors related to their condition. While some of these women die, a proportion of them narrowly escape death defined as “near miss”. By evaluating these cases with severe maternal outcomes much can be learnt about the processes in place (or lack of them) to deal with maternal morbidities [11]. Hence, effective interventions can be implemented to prevent and manage any complications that arise during childbirth [12]. The aim of this study, carried out on more than 55 000 deliveries of 14 different centers of Abruzzo, a central region of Italy, was the evaluation of maternal outcomes and of the associated risk factors occurred from 2009 to 2013.

Methods

Study design

The study considered all the deliveries performed between January 1, 2009 and December 31, 2013 in fourteen hospitals of Abruzzo region, Italy. Information was collected from all hospital discharge records (HDR), using the hospital information system. This system includes information about the demographic characteristics of patients, the diagnoses, and the procedures followed during the hospitalization coded using the International Classification of Disease, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM). The HDR of all women between 10 and 55 years of age, who delivered in the fourteen Maternity Units of the region, were extracted and identified using the Diagnosis Related Group (DRG) codes 370 (Cesarean Section with CC), 371 (Cesarean Section without CC), 372 (Vaginal Delivery with Complicating Diagnoses), 373 (Vaginal Delivery without Complicating Diagnoses), 374 (Vaginal Delivery with Sterilization and/or D&C), 375 (Vaginal Delivery with O.R. procedure Except Sterilization and/or D&C) or the principal or secondary diagnostic codes, V27.xx or 640.xy-676.xy where y=1 or 2, or the intervention codes 72.x, 73.2x, 73.5x, 73.6, 73.8, 73.9x, 74.0, 74.1, 74.2, 74.4 and 74.99. All mothers with one of the following discharge diagnoses were excluded: 656.4 (intrauterine death), V27.1 (single stillborn), V27.4 (twins, both stillborn), v27.7 (multiple birth, all stillborn), 630 (hydatiform mole), 631 (other abnormal product of conception), 633 (ectopic pregnancy), and 632, 634-639, 69.01, 69.51, 74.91, 75.0 (abortion). Moreover, all women non-resident in Italy were excluded. A caesarean delivery (CD) was identified by DRG codes 370 and 371 or ICD-9-CM diagnosis code 669.7x or intervention codes 74.0, 74.1, 74.2, 74.4 and 74.99.

Severe maternal outcomes were extracted and identified using the ICD-9-CM among the principal or secondary diagnostic codes: amniotic fluid embolism (673.10, 673.12,673.14), obstetric pulmunary embolism (673.00, 673.02, 673.04, 673.20 673.22, 673.24, 673.30, 673.32, 673.34, 673.80, 673.82, 673.84), severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (642.50, 642.52,642.54, 642.60, 642.62, 642.64), anesthesiological, cardiological, neurological or pulmonary complication (668.00, 668.02, 668.04, 668.10, 668.12, 668.14, 668.20, 668.22, 668.24), shock (669.10, 669.12, 669.14, 785.5, 998.0), puerperal cerebrovascular disorder (674.00, 674.02, 674.04 671.50, 671.52, 671.54, 430-434, 436, 437), uterine rupture (665.0, 665.1), respiratory distress syndrome (518.5, 518.81, 518.82), pulmonary edema (518.4, 428.1), myocardial infarction (410, 411), severe hemorrhage (666.0, 666.1, 666.2, 666.3 or one of the next procedures 99.0, 68.3-68.4, 68.6), postpartum acute kidney disease (669.3), cardiac arrest or cerebral anoxia next to obstetric surgery (669.40, 669.42, 669.44), assisted ventilation (96.7), respiratory therapy (93.90, 93.91, 93.93), orotracheal intubation (96.01, 96.02, 96.03, 96.04, 96.05) and abdominal hysterectomy. Maternal comorbidity were extracted and identified using the ICD-9-CM among the principal or secondary diagnostic codes: malignant hormone dependent cancer (from 170 to 176), malignant genital cancer (from 179 to 189), other malignant cancer (from 140.0 to 208.9, V10), anemia (from 280 to 285 and 648.2 excluding 648.22 and 648.24), coagulation disorders (286), thrombocytopenia (287.3, 287.4, 287.5), cardiac disease (from 390 to 398, from 412 to 429 excluding 428.1), congenital heart defect (from 745 to 747), cerebrovascular disease (437, 438), nephritic or nephrotic syndrome (from 580 to 589), collagen diseases (710), HIV infection (042, 079.53, V08), thyroid diseases (from 240 to 246, 648.1 excluding 648.12 e 648.14), diabetes (from 250.0 to 250.9, 648.0 excluding 648.02 e 648.04), arterial hypertension (from 401 to 405), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (492, 494, 496), ashtma (493), cystic fibrosis (277.0), acute pulmonary disease (from 480 to 487, from 510 to 514), other chronic pulmonary disease (from 500 to 508, from 515 to 517), tuberculosis (from 010 to 018 and 647.3), amniotic fluid embolism (673.11, 673.13), obstetric pulmonary embolism (673.01, 673.03-673.21, 673.23-673.31, 673.33-673.81, 673.83), hypertension complicating pregnancy (642.01, 642.03-642.11, 642.13-642.21, 642.23- 642.31, 642.33-642.91, 642.9), antepartum pre-eclampsia/eclampsia (642.41, 642.43-642.51, 642.53-642.61, 642.63 - 642.71, 642.73), other renal diseases without hypertension (646.21, 646.23), pregnancy heart diseases (648.51, 648.53-648.61, 648.63), antepartum bleeding/ placenta previa/abruptio placenta (641), preterm delivery (644.2), pregnancy hepatic diseases (646.7), intra-amniotic infection (658.41, 658.43), pregnancy cerebrovascular diseases (671.51, 671.53 674.01, 674.03), cardiac arrest or cerebral anoxia next to obstetric surgery (669.41, 669.43), multiple pregnancy (651, from V27.2 to V27.9, from V31 to V37), other maternal diseases complicating pregnancy (760.0, 760.1, 760.3), substance abuse (from 303 to 305 and 648.3 excluding 648.32 and 648.34), high risk pregnancy (V23.0, V23.2, V23.4, V23.5, V23.7, V23.8), assisted reproduction (V26.1, V26.8, V26.9), uterine lesions (654.91, 654.93) and obesity or overweight during pregnancy (278.0, 646.11, 646.13). The following socio-demographic variables were collected: maternal age, citizenship and marital status.

Statistical analyses

The quantitative variables were summarized as mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR) according to their distribution. The qualitative variables were summarized as frequency and percentage. Chi Square’s test was assessed to evaluate differences in complications between women undergone to CS and to vaginal delivery (VD) and between deliveries performed in hospitals over and under 1000 deliveries per year. Univariate logistic regression analyses were performed to calculate crude odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) for each comorbidity. Stepwise multiple logistic regression models with backward selection were performed to identify predictors of the most frequent unfavorable outcomes and to calculate relative adjusted OR with 95%CI. Only comorbidities with a frequency exceeding ten cases were included into regression model as predictors. Age was also included into account as covariate. Alpha error was evaluated at 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Spss Statistics v20.0 software (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois, USA).

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in conformity with the regulations on data management of the Regional Health Authority of Abruzzo and with the Italian Law on privacy (Art. 20-21 DL 196/2003) published on the Official Journal n. 190 of August 14, 2004. Data were encrypted prior to the analysis at the regional statistical office, where each patient was assigned a unique identifier. This identifier eliminates the possibility to trace the patient’s identity. Administrative data don’t need a specific written informed consent. Therefore, the study was performed in accordance with the Ethical standards laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments.

Results

57, 260 deliveries were analyzed. The mean age of patients was 31.7 ± 5.4 years, 46.6% were married and 84.6% were Italian citizens. 58.8% of the women performed VD and a severe complication occurred in 0.9% of all analyzed deliveries (Table 1). Maternal outcomes are listed in Table 2: the most frequent complications were “Severe Hemorrhage” (0.83%), “Hysterectomy” (0.08%), “Uterine rupture” (0.05%) and “Severe pre-eclampsia/eclampsia” (0.05%). Significant difference was assessed in occurred complications between women undergone to CS and to VD (χ2=14.97, p<0.001). The most frequent comorbidities were “Multiple Pregnancy” (1.5%) and “Hypertension complicating pregnancy” (1.1%) as shown in Table 3. No significant differences were observed in complications among hospitals over and under 1000 deliveries per year (χ2=0.172, p=0.679). Table 4 shows crude and adjusted OR with 95%CI of most frequent maternal outcomes obtained by logistic regression models. Malignant cancer (OR=55.76), coagulation disorders (OR=37.21), acute pulmonary disease (OR=29.75), placenta previa (OR=26.51), caesarean section (OR=3.24) and age (OR=1.08) were associated with a significantly higher risk of hysterectomy. Malignant genital cancers (n=2), resulted the only one type of tumor predicting hysterectomy with OR=362.16 (95%CI=6.90-19016.55, p-value<0.001). Anemia (OR=14.64), coagulation disorders (OR=10.31), cardiac disease (OR=12.74), pregnancy hypertension (OR=2.66), major preeclampsia/ eclampsia (OR=2.78), placenta previa (OR=9.42) and multiple pregnancy (OR=3.69) were associated with a significantly higher risk of severe hemorrhage. Thrombocytopenia (OR=26.04) and diabetes (OR=5.05) were associated with a significantly higher risk of uterine rupture. Overweight or obesity (OR=25.88) and pregnancy cardiovascular disease (OR=25.85) were associated with a significantly higher risk of pre-eclampsia.

| Variables | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age | 31.7 ± 5.4 |

| Marital status n (%) | |

| Married | 26 660 (46.6) |

| Nubile | 8549 (14.9) |

| Separed | 26 (0.5) |

| Divorced | 222 (0.4) |

| Widow | 63 (0.1) |

| Not declared | 21 499 (37.5) |

| Citizenship n (%) | |

| Italian | 48 416 (84.6) |

| Foreign | 8844 (15.4) |

| Mode of delivery n (%) | |

| Vaginal | 33 676 (58.8) |

| Cesarean | 23 584 (41.2) |

Table 1: Socio-demographic variables.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Severe hemorrhage | 478 (0.83) |

| Hysterectomy | 46 (0.08) |

| Uterine rupture | 27 (0.05) |

| Major pre-eclampsia/eclampsia | 26 (0.05) |

| Shock | 5 (0.01) |

| Cerebrovascular complication | 2 (0.00) |

| Obstetric embolism | 1 (0.00) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (0.00) |

| Anesthesiological, cardiological or pulmonary acute complication | 1 (0.00) |

| Amniotic fluid embolism | 1 (0.00) |

| Acute kidney disease | 1 (0.00) |

| Total | 589a (0.94) |

Table 2: Maternal outcomes.

| Variables | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Multiple pregnancy | 851 (1.49) |

| Hypertension complicating pregnancy | 656 (1.15) |

| Preterm delivery | 568 (0.98) |

| Antepartum bleeding/placenta previa/abruptio placentae | 559 (0.98) |

| Diabetes | 500 (0.87) |

| Antepartum pre-eclampsia/eclampsia | 469 (0.82) |

| High risk pregnancy | 424 (0.74) |

| Assisted reproduction | 395 (0.69) |

| Anemia | 256 (0.45) |

| Pregnancy hepatic diseases | 170 (0.30) |

| Thyroid diseases | 63 (0.11) |

| Thrombocytopenia | 53 (0.09) |

| Obesity or overweight during pregnancy | 46 (0.08) |

| Other renal diseases without hypertension | 37 (0.06) |

| Coagulation disorders | 32 (0.06) |

| Pregnancy heart diseases | 28 (0.05) |

| Cardiac disease | 22 (0.04) |

| Uterine lesions | 22 (0.04) |

| Hiv infection | 19 (0.03) |

| Acute pulmonary disease | 15 (0.03) |

| Arterial hypertension | 13 (0.02) |

| Intra-amniotic infection | 11 (0.02) |

| Congenital heart defect | 10 (0.02) |

| Malignant cancer | 10 (0.02) |

| Malignant hormone dependent cancer | 3 (0.01) |

| Malignant genital cancer | 2 (0.01) |

| Other malignant cancer | 5 (0.01) |

| Others | 34 (0.06) |

Table 3: Maternal comorbidity.

Discussion

Obstetric admissions are the leading cause of hospitalization for women [4,13] and the improvement in safety and quality of care is a fundamental issue [14]. Improving the quality of care requires reducing the use of obstetric intervention which can harm babies (e.g. early delivery) and mothers (e.g. unnecessary caesarean delivery). However the measures we assessed do not reflect the quality of care in terms of severe maternal or neonatal morbidity [15]. This study assessed that in Abruzzo region, the 41.2% of women underwent to CS. This proportion remains over the threshold fixed by WHO [16]. The proportion of maternal adverse outcomes was higher than the national one (0.94% versus 0.76%) [17]. Severe peripartum hemorrhage, defined as estimated blood loss >1500 ml, peripartum fall in hemoglobin concentration ≥ 40 g/l or acute transfusion or hemorrhage requiring hysterectomy [18] was the most frequent complication, occurred in the 0.83% of the women of this study. This result was in agreement with many other studies, that shown severe hemorrhage as a major and rising delivery complication [19]. The findings of this study were not consistent with some commonly held belief that increasing rates of severe hemorrhage are due to changes in maternal characteristics and obstetric procedures as increases in maternal age, cesarean section and induction/augmentation of labor or epidural use, as confirmed by Ford et al. [20]. The strongest risk factors for postpartum hemorrhage reflected those found in other studies. Anemia, Cardiac disease, Coagulation disorders, Pregnancy hypertension, Placenta previa, Multiple pregnancy, and Major pre-eclampsia/eclampsia were the strongest predictors of severe hemorrhage after adjustment for other factors [21-24]. Furthermore, hysterectomy is significantly predicted by malignant cancer, coagulation disorders, acute pulmonary disease, placenta previa, caesarean section and maternal age. Concerning malignant cancer, the OR value was totally influenced by malignant genital cancers rather than other malignant ones (OR 362.16, p=0.004), as resulted in a stratified sub analysis. Other studies demonstrated the influence of malignant genital cancers on the risk of hysterectomy [25]. Coagulation disorders had a significative OR for hysterectomy as confirmed by Awan et al. [26], and Sahin et al. [27]. Other studies assessed the influence of acute pulmonary disease [28] and of placenta previa [29,30] on the risk of hysterectomy. About uterine rupture, the results of this study were not consistent with the commonly held knowledges. In particular, thrombocytopenia, known risk factor for severe hemorrhage [31], showed a high risk for uterine ruptures (OR=26.04), in contrast with Yuce et al. [32]. This study confirmed diabetes as uterine rupture risk factor, probably due to excess of birth weight [33]. At least, major pre-eclampsia and eclampsia were significantly predicted by cardiovascular disease and maternal overweight and obesity. Cardiovascular diseases are confirmed as potential risk factors according to previous studies [34]. Maternal obesity is a known risk factor for pre-eclampsia, having a larger effect on placenta insufficiency [35]. The results of this study should be considered in the light of the following limitations: first, the identification of severe complications is based on ICD-9-CM codes, that did not take into account the severity of conditions. Second, the use of administrative data may be limited by the reliability of certain types of information such as drugs therapy, parity, details about the timing of delivery (elective or emergency procedure), duration of labor and conditions of impending maternal compromise. This lack of information compromises the model of risk-adjusting outcomes because do not allow to consider relevant clinical variables. Nonetheless the aim of this study was not the measurement of the process of care, but to evaluate whether presence of comorbidity could explain differences in outcomes.

Conclusions

This study showed that severe maternal outcomes occurred in about 1 of 100 deliveries in Abruzzo region. Maternal comorbidities are associated with increased risk of complications and may result in substantial costs to the health care system. These results aim to focus the attention on the need in preventing and managing maternal comorbidities to avoid the occurrence of adverse outcomes. However, we are aware that more research is required to develop a consensus about accepted, reproducible and clinically relevant indicators of maternal and neonatal outcomes.

Acknowledgments

Authors are very grateful to Vito Di Candia (Agenzia Sanitaria Regionale Abruzzo, Italy) for helping in data collection and to Marzia Iasenza (PhD in English Linguistics) for reviewing the English manuscript.

References

- Kassebaum NJ, Villa BA, Coggeshall MS, Shackelford KA, Steiner C, et al. (2014) Global, regional, and national levels and causes of maternal mortality during 1990-2013: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2013. Lancet 384: 980-1004.

- Shiffman J, Smith S (2007) Generation of political priority for global health initiatives: a framework and case study of maternal mortality. Lancet 370: 1370-1379.

- Serour GI (2012) The role of FIGO in women's health and reducing reproductive morbidity and mortality. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 119: 53-55.

- Health Imo (2016) Rapporto annuale attività ricovero, 2015.

- Programme, WHO, UNICEF (1993) Indicators to monitor maternal health goals : report of a technical working group. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Villar J, Valladares E, Wojdyla D, Zavaleta N, Carroli G, et al. (2006). Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet 367: 1819-1829.

- World Health Oraganization (2011) Evaluating the quality of care for severe pregnancy complications. The WHO near-miss approach for maternal health.

- Farchi S, Polo A, Franco F, Lallo DD, Guasticchi G (2010) Severe postpartum morbidity and mode of delivery: a retrospective cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand89: 1600-1603.

- Maso G, Monasta L, Piccoli M, Ronfani L, Montico M, et al. (2015) Risk-adjusted operative delivery rates and maternal-neonatal outcomes as measures of quality assessment in obstetric care: a multicenter prospective study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15: 20.

- Wen SW, Huang L, Liston R, Heaman M, Baskett T, et al. (2005) Severe maternal morbidity in Canada, 1991-2001. CMAJ 173: 759-764.

- Say L, Pattinson RC, Gulmezoglu AM (2004) WHO systematic review of maternal morbidity and mortality: the prevalence of severe acute maternal morbidity (near miss). Reprod Health 1: 3.

- Campbell OM, Graham WJ (2006) Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Lancet 368: 1284-1299.

- Bailit JL (2007) Measuring the quality of inpatient obstetrical care. Obstet Gynecol Surv 62: 207-213.

- Srinivas SK, Fager C, Lorch SA (2010) Evaluating risk-adjusted cesarean delivery rate as a measure of obstetric quality. Obstet Gynecol 115: 1007-1013.

- Howell EA, Zeitlin J, Hebert PL, Balbierz A (2014). Association between hospital-level obstetric quality indicators and maternal and neonatal morbidity. JAMA 312: 1531-1541.

- WHO Statement on caesarean section rates (2015) Reprod Health Matters 23: 149-150.

- Agenas (2016) Programma Nazionale Esiti 2015.

- Waterstone M, Bewley S, Wolfe C (2001) Incidence and predictors of severe obstetric morbidity: case-control study. BMJ 322: 1089-1093 .

- Callaghan WM, Kuklina EV, Berg CJ (2010) Trends in postpartum hemorrhage: United States, 1994-2006. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202: 351-356.

- Ford JB, Roberts CL, Simpson JM (2007) Increased postpartum Hemorrhage rates in Australia. Int J Gynecol Obstet 98: 237-243.

- Ehrenthal DB, Chichester ML, Cole OS, Jiang X (2012) Maternal risk factors for peripartum transfusion. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 21: 792-797 .

- Cauldwell M, Klemperer VK, Uebing A, Swan L, Steer PJ, et al. (2016) Why is post-partum haemorrhage more common in women with congenital heart disease? Int J Cardiol 218: 285-290.

- Butwick AJ, Goodnough LT (2015) Transfusion and coagulation management in major obstetric hemorrhage. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 28: 275-284.

- Kramer MS, Berg C, Abenhaim H, Dahhou M, Rouleau J, et al. (2013) Incidence, risk factors, and temporal trends in severe postpartum hemorrhage. Am J Obstet Gynecol 209: 441-447.

- Thompson JD, Birch HW (1981) Indications of hysterectomy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 24: 1245-1258.

- Awan N, Bennett MJ, Walters WA (2011) Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: a 10-year review at the Royal Hospital for Women, Sydney. Aust NZJ Obstet Gynaecol 51: 210-215.

- Sahin S, Guzin K, Eroglu M, Kayabasoglu F, Yasartekin MS (2014) Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: our 12-year experience. Arch Gynecol Obstet 289: 953-958.

- Yancey MK, Harlass FE, Benson W, Brady K (1993) The perioperative morbidity of scheduled cesarean hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 81: 206-210.

- Bodelon C, Bernabe-Ortiz A, Schiff MA, Reed SD (2009) Factors associated with peripartum hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol 114: 115-123.

- Reyal F, Sibony O, Oury JF, Luton D, Bang J, et al. (2004) Criteria for transfusion in severe postpartum hemorrhage: analysis of practice and risk factors. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 112: 61-64.

- Dikman D, Elstein D, Levi GS, Granovsky-Grisaru S, Samueloff A, et al. (2014) Effect of thrombocytopenia on mode of analgesia/anesthesia and maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 27: 597-602.

- Yuce T, Acar D, Kalafat E, Alkilic A, Cetindag E, et al. (2014) Thrombocytopenia in pregnancy: do the time of diagnosis and delivery route affect pregnancy outcome in parturients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura? Int J Hematol 100: 540-544.

- Hesselman S, Hogberg U, Ekholm-Selling K, Rassjo EB, Jonsson M (2015) The risk of uterine rupture is not increased with single- compared with double-layer closure: a Swedish cohort study. BJOG122: 1535-1541.

- Chen CW, Jaffe IZ, Karumanchi SA (2014) Pre-eclampsia and cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Res 101: 579-586.

- Djelantik AA, Kunst AE, Wal VD, Smit HA, Vrijkotte TG (2012) Contribution of overweight and obesity to the occurrence of adverse pregnancy outcomes in a multi-ethnic cohort: population attributive fractions for Amsterdam. BJOG 119: 283-290.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi