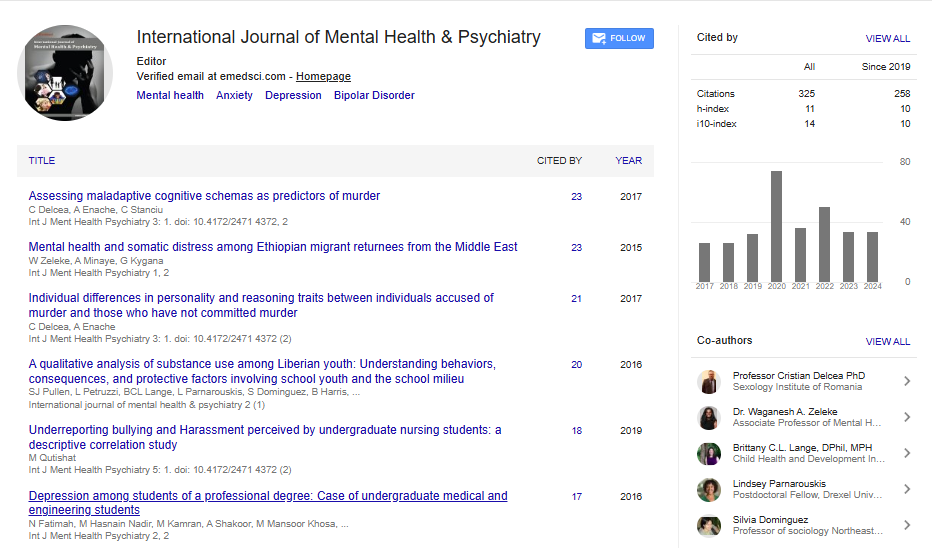

Case Report, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 6 Issue: 3

Case Series of Suicide Attempts during the Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Lockdown

Olashore AA*, Akanni OO, Bojosi K and Garechaba GDepartment of Psychiatry, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana Clinical Services, Federal Neuropsychiatric Hospital, Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria

*Corresponding Author : Olashore AA

Department of Psychiatry, Faculty of

Medicine, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

Tel: +2673555514

EMail: olawaleanthonya@gmail.com

Received date: May 18, 2020; Accepted date: June 01, 2020; Published date: June 08, 2020

Citation: Olashore AA, Akanni OO, Bojosi K, Garechaba G (2020) Case Series of Suicide Attempts during the Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Lockdown. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 6:3. doi: 10.37532/ijmhp.2020.6(3).180

Abstract

COVID-19 has been declared a global pandemic. It has severe effects on all facets of life, including the physical and mental health of people. Although social isolation has been effective in curbing the spread, the psychological effects of reduced contact and communication, such as anxiety, suicide, and depression, are beginning to manifest. We present three cases with the first episode of suicidal attempts in a mental institute in Botswana during the COVID-19 lockdown. While these reports lack the statistical ability to link this lockdown to psychological distress, they point to an urgent need for research to evaluate and address the effect of this social disconnect on people's psychological health.

Keywords: COVID-19; Suicide; Pandemic; Lockdown; Corona virus

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has been declared a global pandemic by the World health organization; over 4 million persons have been infected worldwide, and the rate of deaths per number of diagnosed cases is 4.1% [1]. Advice regarding self-isolation and social distancing has proven to be very useful and significantly reduced the rate of spread all over the world. In Botswana, measures taken to ensure compliance to the lockdown include mounting various military and police roadblocks, issuing movement permits to workers with essential services, and distributing groceries to the needy or those who are not permitted to move around. Despite the measures to curtail the pandemic, the outbreak of this highly infectious and fast-spreading deadly virus has been associated with a high rate of anxiety disorder because of uncertainty in contracting the virus [2]. Furthermore, the psychological effects of reduced contact and communication, such as anxiety and depression, are beginning to manifest [1, 2]. Hence, we present three separate cases of individuals with the first episode of suicidal attempt in a mental institute in Botswana during the COVID -19 pandemic lockdown.

Case Series

Case 1

A 31-year-old single male hairdresser was referred from a local clinic with a 3-day history of feeling sad, hopeless, struggling to fall asleep, loss of appetite, low mood, suicidal thoughts. The patient said the above symptoms started a couple of days after the national lockdown due to COVID-19. He attributed the symptoms to being alone in the house and facing the uncertainty of not knowing how everything was going to evolve. He began to be preoccupied with the thoughts of challenging life issues he had previously avoided. This included thinking a lot about his 5-year-old son, whom he had not seen in more than two years. He had been separated from the mother of the child since 2017 after a 4-year relationship with the woman. He avoided thinking about this problem by keeping himself busy at work and hanging around friends at work until the lockdown. Another troubling matter was the death of his mother and two siblings, which happened some years ago; he suddenly found himself recalling and ruminating on the painful memories. He realized he did not properly grieve the losses of his loved ones. All these terrible memories and thoughts eventually led him to a decision to take his life by hanging. However, he was rescued and brought to the hospital for treatment by his neighbors, who heard some grunting and retching sounds from his room.

There was no anxiety symptom or features suggestive of a psychotic disorder before the suicide attempt. He takes only alcohol and cigarette occasionally. He is HIV positive and has been on treatment with undetectable viral load. He has no symptoms suggestive of any medical or organic disorder. There was no significant finding observed on mental state examination than a sad mood and preoccupation with a suicidal idea. Investigations revealed no significant abnormalities.

Case 2

A 34-year-old married female intern presented with a week history of symptoms as the first case. Before the period of lockdown, she had been having some problems with her husband. These problems included misappropriation of family funds by the husband, disagreement over his choice of friends, and habits. According to her, she was able to manage these issues by seeking supports from friends at work, occupying herself with work, and staying away from the husband most of the time. She was able to avoid her husband successfully because the man works as a security guard at night; she leaves for work in the morning before the husband returns from work, and then she comes late after the husband has gone to work in the evening. Thus, she had avoided confrontations and disagreements with the husband until the lockdown when the two of them forcibly had to be home together. During the lockdown, the disagreement escalated to constant physical and emotional abuse by the husband. She consequently became frustrated and decided to end her life by hanging. In preparation for this attempt, she dropped a note, ensured the husband had left the apartment to play with their neighbors and locked the door to the apartment. Fortunately, the husband who needed to pick something from the apartment, on returning, discovered the door was locked from the other side. Following the patient ’ s failure to respond after several knocks, he alerted the neighbors who assisted in breaking down the door. On breaking the door, she was found on the freezer, with a rope around her neck about to be tied to the ceiling. It was at that moment she was rescued. Her mental state on admission was like that of the first case.

Case 3

A 25-year-old single male security guard presented with a week history of sadness, irritability, hopelessness, and suicidal ideation. He was apparently well until a few days after the lockdown when he was informed that his only daughter, who was staying with his exgirlfriend, was being neglected by her. His ex-girlfriend's landlord informed him of two occasions when the child was left outside unattended to and an occasion when the new boyfriend physically abused the child. To retrieve the child, and because of non-available transport due to the lockdown, he trekked about 36 kilometers in the night. On reaching the place where he presumed his daughter was, he was told it was the wrong address of their location. Unfortunately, he was unable to proceed further that night and could not reach other members of the family for assistance due to the restriction of movement. He felt so angry, frustrated, helpless, and hopeless about this situation. Consequently, he decided to kill himself by hanging on a tree in deserted farmland. Before the attempt to kill himself, he left a suicide note. He was discovered hanging on a tree by a passer-by who rescued him and handed him to the police who brought him to the mental facility.

Discussion

Suicide, which is the act of deliberately terminating one’s own life [3], has always been in the global public health purview because it is the third leading cause of death worldwide among those in the age group 15 – 24 years [4]. The unabated spread of the coronavirus, attendant spate of fatalities, and accompanying social changes is thought to spike up the occurrences of suicide probably. This is the case in the previous pandemic, epidemic, and crisis [5]. As of April 30, 2020, COVID-19 had caused the unfortunate deaths of over 200,000 persons and adversely affected the socio-economic status of people worldwide, such as job losses, financial difficulties, and social isolation [5, 6]. Hence, this has informed our decision to report the emerging series of cases of suicide attempts during the COVID-19 pandemic and restrictive measures in Botswana.

The first case reports described above fit the typical profile of someone attempting suicide who, until the lockdown imposed by the government, was able to cope with his distress. Our formulation was that the young man had an underlying and prolonged relationship problem, which made him vulnerable to a mental breakdown. Before breaking down, he was able to cope and deal with his despondency using his work to distract him from depression. It is also possible that he was abusing alcohol to suppress his depression, but his wall of defense crumbled when an extra stressor, which was a fall out of the COVID-19 restriction was added. He was unable to make a daily living for himself, which limited his economic power to purchase alcohol to medicate himself. Furthermore, he lost the protective effect of work because of the lockdown, which led to his elastic capacity being stretched beyond what he could bear.

The second case was about a woman who was able to cope with or manage her dysfunctional relationship by spending more time away from her husband before the imposed lockdown forced them to stay together for an extended period. This also increased her exposure to physical and emotional abuse, which hitherto had never happened because the couple hardly spent time together. Whilst avoidance may not be the best solution to this marital crisis; it had helped prevent this woman from domestic abuse and its mental consequences, such as suicide. The fear of dwindling family resources, uncertainty about the future, or the possibility of becoming unemployed after the lockdown may likewise have contributed to the escalation of the marital crisis and its attendant violence. Authors have reported that the tension bred by forced proximity during COVID-19 has led to an unprecedented high incidence of family discord and domestic violence [7, 8]. Consequent to this epidemic lockdown, many couples have been bound with each other at home for over a month, and this has created a highly inflammatory environment for a marital feud. Divorce or separation, which could have been an option for some of these abusive relationships, was difficult to pursue because of the limited access to court for filing. In addition to the lack of social support during this lockdown, this problem may have possibly left some victims with the option of committing suicide as the only way of escape. While efforts are being made to address this pandemic's economic impacts, there is also an urgent need to discover, evaluate, and refine a mechanistically driven intervention to address the psychological sequelae of this pandemic lockdown.

The third case further buttresses the limited availability of help and social support during this period. Despite the risk and stress, he went through to save his child who was in need; he was unsuccessful due to the restriction of movement and limited access to family or social support. Every other family member he reached out to for assistance was unable to help due to movement restriction. This possibly led him to consider suicide as the only way to escape from his stressful condition.

Thus, these reports are a wake-up call for stakeholders to take the matter of suicide seriously, particularly in this period of COVID-19, because of associated catastrophic social changes that are occurring that are known to precipitate suicide ideas. Several other contributory factors to suicide associated with the pandemic related changes exist, which have not been mentioned, and they include loss of a loved one to the coronavirus disease, stigmatization of an infected individual, and irresponsible media reporting [5]. The pathway to suicide during the pandemic is thus, myriad. To eradicate COVID-19, global players should not be distracted from giving necessary attention to the suicide menace, which will continue to be with us even after the COVID-19 pandemic. While the pandemic is with us and even after, the government at every level must put measures in place to cushion the effect of the lockdown and make the socio-economic life of their citizen better (e.g., providing food, housing, and unemployment supports). Health practitioners should be sensitive and vigilant to their clients' needs so that suicide ideation can be detected early, while there should be increased support for mental health helplines. Individuals must learn how to cope with their distress by accepting and adjusting their expectations when nothing can be done, staying connected to their families and friends, and relaxing to control their emotions.

Conclusion

COVID-19 appears to be the most urgent public health importance at the time of writing, because of its high contagion and deadly nature. Studies linking the pandemic lockdown to the increase in psychologic distress, and its effects, such as suicide, is almost non-existent. The cases reported have shown different ways by which social distancing and restriction of movement have affected the mental health of some individuals who consequently believed suicide was the only way to cope. Whilst this write up is limited in its ability to link the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown to psychological distress statistically, it is a warning to an urgent need for research to evaluate and address the effect of this social disconnect on the psychological health of people.

Furthermore, COVID-19 should be a drive and not a deterrent towards the aggressive prevention of suicide. Suicide attempts intervention during this period also merits a corresponding response in an action plan the way it is being done for COVID-19.

Consent for Publication

Competing interests

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Organization WHO (2020) Coronavirus disease 2019 ( COVID-19): situation report 49.

- Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, et al. (2020) Immediate Psychological Responses and Associated Factors during the Initial Stage of the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Epidemic among the General Population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17: 1729.

- Shneidman ES (1998) The suicidal mind: Oxford University Press USA.

- Giru BW (2016) Prevalence and Associated Factors of Suicidal Ideation and Attempt Among High School Adolescent Students in Fitche Town, North Shoa, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, 2012: Institutional Based Cross Sectional Study. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing 23.

- Gunnell D, Appleby L, Arensman E, Hawton K, John A, et al. (2020) Suicide risk and prevention during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 468-471.

- WorldOMeters (2020) COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic.

- Bradbury‐Jones C, Isham L (2020) The pandemic paradox: the consequences of COVID‐19 on domestic violence. J Clin Nurs.

- Holmes EA, O'Connor RC, Perry VH, Tracey I, Wessely S, et al. (2020) Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 7: 547-560.

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi