Editorial, Int J Ment Health Psychiatry Vol: 3 Issue: 1

Attachment, Acculturative Stress, Social Supports, Separation and Marital Distress in Mexican and Central American Adult Immigrants Separated from Primary Caregivers as Children

| Isaac Carreon1* and Susan L Rarick2 | |

| 1Pacific Oaks College, Adjunct faculty, School of Cultural and Family Psychology, 55 Eureka Street, Pasadena, CA 91103, United States | |

| 2Walden University, Core Faculty, School of Psychology, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, 100 Washington Avenue South, Suite 900, Minneapolis, MN 55401, United states | |

| Corresponding author : Isaac Carreon Pacific Oaks College, Adjunct faculty, School of Cultural and Family Psychology, 55 Eureka Street, Pasadena, CA 91103, United States E-mail: icarreon@pacificoaks.edun |

|

| Received: March 16, 2017 Accepted: March 20, 2017 Published: March 25, 2017 | |

| Citation: Carreon, I., Rarick, S.L (2017) Attachment, Acculturative Stress, Social Supports, Separation and Marital Distress in Mexican and Central American Adult Immigrants Separated from Primary Caregivers as Children. Int J Ment Health Psychiatry 3:1. doi: 10.4172/2471-4372.1000e103 |

Abstract

Latinas/os are reported to be the fastest growing ethnic minority in the United States, with a large percentage being newly arrived immigrants. Previous research has found that many migrate in phases, with the father leaving the family behind or both parents migrating and leaving children in the care of family members. Separations from parental figures have been found to lead to psychosocial, psychological, and educational problems, acculturative stress, lack of social support, attachment problems, poverty, discrimination, unemployment, and marital distress. The purpose of this study was to inquire if immigrant variables (attachment, acculturative stress, and social supports) in Mexican and Central American immigrants who were separated from their primary caregivers as children predict marital distress. A total of 92 participants completed either the online questionnaire via Survey Monkey or paper surveys in person. A quantitative methodology, correlational multiple regression model was used in order to investigate the research questions and hypotheses. The theoretical framework that guided this study was John Bowlby’s Attachment Theory. The results from the current study showed a statistically significant finding that the attachment style and acculturative stress in Mexican and Central American immigrants predicted marital distress. Findings from this study can promote a deeper understanding to marriage counselors regarding attachment, social support, acculturative stress, and separation factors that can affect immigrant couples. It may also have implications for immigration policy and promote the establishment of reunification programs in communities where immigrant populations reside.

Keywords: Latina/o immigrants; Marital Distress; Attachment; Acculturative Stress; Social Support; Separation

Keywords |

|

| Latina/o immigrants; Marital distress; Attachment; Acculturative stress; Social support; Separation | |

Introduction |

|

| The U.S. Census reported that there are approximately 40 million immigrants in the United States with at least 11 million here illegally [1]. There are approximately 13% immigrants living in the United States. In 2013, Latina/o immigrants were 46% of the total U.S. immigrant population. Dillon, De La Rosa, Sastre, and Ibañez [2] reported that by the year 2050 the Latino population will account for more than half of the nation’s population. | |

| Traditionally, many families migrate to the United States in phases. Usually one or both parents migrate first to find work and save money, and the children are left behind with family members [3]. During their parents’ absence, children are usually left with grandparents or other family members, while the mother begins sending money to the caretakers and saving money for the children’s journey into the United States. At times, children can remain in Mexico with their caretakers for months and even years. | |

| Several studies examining the relationship between immigration and psychological and psychosocial problems have been published [4,5]. Researchers have also examined Mexican immigrants separated from primary caregivers when migrating as children and how they may develop high levels of acculturative stress and low levels of social support after entering the United States [6,7]. In addition, acculturative stressors have been noted to increase psychological distress, depression symptoms, suicidal ideation, alcohol and drug use, and marital distress [5,8]. | |

| Research has shown that Mexican immigrants who were separated from primary caregivers when migrating as children may have a lack of social support and experience acculturative stress upon entering the United States [6,7]. These challenges have been correlated with marital distress, which attachment theory attributes to an avoidant attachment style that develops as a stress coping method [9]. Researchers have noted acculturative stress, loss of support networks, discrimination, and family conflicts to increase psychological distress, depression symptoms, suicidal ideation, alcohol and drug use, and marital distress [4,5,8,10]. | |

| Acculturative stress | |

| One of the biggest challenges faced by many immigrants is the psychosocial and emotional balance between their home country (family, food, language) and adapting to their host country [11]. Berry defined acculturation as the process of changes in beliefs, attitudes, values, and behaviors that are a result of contact with another culture [12]. Acculturative stress is then defined as “the loss of familiar ways, sounds, and faces, coupled with a sense of not knowing quite how to belong, connect and get support” [13]. Many times when families emigrate, the acculturation process does not occur the same for parents as it does for children. Parent and child discrepancy in acculturation can lead to risk factors of child maladjustment [14]. This discrepancy can create separation between parents and their children especially when children were left behind and rejoin their parents years later. Children may see caretakers as parental figures, which may lead to resentment or even denial of their real parents as their own [15]. | |

| Social supports of immigrant families | |

| A prominent struggle for the Mexican and Central American immigrant is the loss of social support when entering the United States. Menjivar argued that migrants rely on kinship networks to obtain material, financial and emotional support [16]. However, struggles with finding social support in a new culture can bring on psychological problems [17]. Acculturative stressors can also increase poor health, alcohol and drug use, family conflicts, and marital distress [5]. However, Mexican-Americans have many barriers to mental health services. These barriers are due to finances, proximity to mental health clinics outside of Latino communities, culturally irrelevant therapeutic approaches including a lack of Spanish-speaking therapists, and lack of ethnically similar counselors [18]. In addition, according to the cultural barrier theory, the Latino culture predisposes Mexican immigrants to not seek professional services due to traditional Mexican values such as familism and religiosity [18]. | |

Marital Distress among Latina/o Immigrants |

|

| Understanding migration’s impact on couples is important especially given reports of marital distress, separation, and domestic violence [19]. Some of the common stressors in migrant couples include health and social service barriers, finding employment, not having safe and affordable housing, obtaining professional accreditation, discrimination, loss of social status, isolation, acculturative stress, language, and economic problems [20]. Acculturative stress can impact many immigrant couples. Even when migration is intended to benefit the family, there may be strain in marital relationships. For example, migration may increase women’s role in the labor market. This can result in women’s financial independence, social mobility and autonomy [19]. As a result of this shift, distribution of power in the relationship and the family may change. Women’s new role may create problems in the relationship, as men may not accept his new role within the marriage. | |

| Theoretical framework | |

| Bowlby’s attachment theory was the theoretical framework for this study. Attachment theory posits that individuals have an instinctual drive to form a bond with others, specifically their primary caregivers (parents) [21,22]. Later, Mary Ainsworth also added to the theory when she conducted an experiment called The Strange Situation where she made direct observations of infant-mother interactions and their attachments [23]. Bowlby argued that the primary caregiver is a prototype for future relationships [24]. Individuals develop internal working models [22] which remain intact throughout life. Individuals attempt to preserve the primary attachment relationships because these relationships are crucial to the child’s physical and emotional survival. Bowlby argued that attachment to primary caregivers is a survival mechanism for children [22]. | |

| Bowlby identified a total of five attachment styles. Bowlby agreed that secure attachment is observed if children’s needs are met, if they feel worthwhile, and if they can trust their primary caregivers as well as others [23]. The avoidant attachment style is a child or individual that has learned that loved ones are unavailable to them. The anxious ambivalent attachment is when the child or individual has learned that they should protest to get attention and to get their needs met. They also have learned that adults are not dependable or they cannot depend on anyone [23]. The disorganized attachment style is one that is formed in children whose internal working model signals that people are dangerous. Because they believe people are dangerous, they are vigilant and untrusting. Finally, the indiscriminate attachment style is when children had a neglected experience and they overcompensate by attempting to make as many connections with other people as a way to get their needs met [24]. Because the child has internalized attachment styles in their working models, they develop in cognitive schemas, making it difficult for them to form secure attachments. As a result, children may expect the same in future relationships. Consequently, children’s initial attachments influence and can affect their subsequent relationships with others. This study focused on how attachment theory applies to adult immigrants from Mexico and Central America who were separated from their primary caregivers as children due to immigration. | |

| Attachment and immigration | |

| Immigration can affect a person’s attachment. As Bowlby described, humans have a tendency to remain in a familiar and particular locale and in the company of those familiar to them. Immigrants have broken this mold described by Bowlby, Ainsworth, and others [13]. As mentioned previously, immigrants suffer from immigration trauma during the pre-migration, migration, and post migration process [13,25]. According to attachment theory, attachment representation can be compromised during the immigration process. | |

| In a study on immigration, van Ecke reported that out of 400 children, 80% had experienced separation from parents. Immigrant children can experience distress especially when parents leave them behind due to immigration. Immigrant children can develop anxiety, fear, anger, and sadness [26]. Dillon and Walsh suggested that, prolonged separation where the interplay of rejection, abandonment, and poor communication occurs could compromise the bond between the caregiver and the child [26]. This disruption can result in insecure attachment and forms the foundation of future affectional bonds such as marriage. Polanco-Hernandez found that children who remained in their country of origin (Mexico) experience the most emotional distress when their mothers migrated to the United States [27]. Hernandez conducted a study on Mexican, Nicaraguan, and Honduran adolescents ages 14-20 and found that they suffered negative effects on parent-child relationship [28]. During time of reunification they had a difficult time adjusting to a new family arrangement because they experienced two losses, the caregiver they left behind to reunify with parents and the difficulty to form a bond with the parents. Having adequate social support may make it easier for children to reunify with their parents. However, reunification may be difficult if immigrant children and adolescents do not have adequate social supports. | |

| Current study | |

| While some studies have focused on how immigration affects families, there is a gap in the literature on examining how acculturative stress, attachment, and low levels of social support predict marital distress in immigrant couples. Marital distress is one of the reasons why many people seek counseling. Negy argued that marital distress could lead to domestic violence, child behavioral problems, and divorce [5]. According to Rebeiro Latina/o immigrants may be exposed to psychosocial stressors that are not common to other couples [7]. Clinicians should be prepared to understand the myriad of problems with which immigrant families are faced. Moreover, therapeutic interventions should be modified to match the specific cultural needs of the Latina/o clients. Psychologists thus must be sensitive in working with the Latina/o immigrant. Given the lack of research of adults who were separated from their parents as children due to immigration and the acculturative stress during their migration and post migration experience, the current study focused on whether attachment, acculturative stress, separation, and social supports predict marital distress in Mexican and Central American adult immigrants who were separated from their primary caregivers. The study was designed to answer the following three research questions: (1) Does attachment style predict marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children?; (2) Does acculturative stress predict marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children?; and (3) Do social supports predict marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children? | |

Method |

|

| Participants and procedure | |

| Following approval from IRB, flyers were posted in various agencies in southern California that work with immigrant couples. The potential participants were instructed to copy the Survey Monkey link in order to participate in the study. Participants with no access to a computer or the Internet were instructed to contact the researchers in order to participate in the study in person. | |

| Participants in the current study were 92 adult married Mexican and Central American immigrants over the age of 18. Thirty completed hard copy surveys in person, and 62 completed the surveys online. The majority of the participants were between the ages of 31 and 40 (39.1%) and 21 to 30 years of age (32.6%). The majority of the respondents were born in Mexico (72.8%), and the rest were born in Central America (27.2%). The age of separation ranged from 2½ months to 17 years of age. The majority (69.5%) of the respondents were left behind with one or both of their grandparents. The largest percentage of the participants (36%) reported reunifying with their parents at a later age between 17 and 22 years of age, and 16.3% reported never reunifying with their parents after separation. | |

| Measures | |

| Demographic variables: Participants provided demographic information including their age, gender, marital status, country of origin, employment status, salary range, age when separated from their parents, age when they were reunified with their parents, and the family member they were left behind with. | |

| Psychosis Attachment Measure (PAM): Participants’ attachment style was measured utilizing the Psychosis Attachment Measure (PAM). The PAM is composed of 16 items that assesses the two dimensions of adult attachment. The anxiety (8 items) dimension and avoidance (8 items) dimension are measured by the PAM. The PAM measures the two attachment dimensions of anxiety and avoidance, relationships, and the impact of earlier interpersonal experiences on current relationships [29]. In addition, the PAM was chosen because of its practicality, validity, and short time that it takes to complete the measure. The 4-point scale is as follows: not at all (1), a little (2), quite a bit (3), and very much (4). The PAM is scored by adding each dimension. Items 2, 4, and 9 are reverse scored. Higher scores mean more insecurity. The PAM has good psychometric properties in two non-clinical samples. The PAM has good construct validity. Berry found positive associations between low self-esteem and insecure attachment [29]. Also, insecure attachment had a positive association with interpersonal problems, and negative experiences in early interpersonal relationships [9]. In addition, the PAM has also shown concurrent validity and associations between attachment anxiety and avoidance [9]. The anxiety and avoidance dimensions had Cronbach alphas of 0.82 and 0.75 respectively [29]. The subscale scores for anxiety and avoidance were arrived by averaging the 8 anxiety items and 6 avoidance items. The PAM Spanish version Cronbach’s alpha is 0.81 for the anxiety subscale and 0.78 for the avoidance subscale [30]. The PAM demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.86 for the anxiety dimension and .83 for the avoidance dimension). | |

| Marital Stress Inventory-Revised (MSI-R): The MSI-R was used to assess participants’ marital satisfaction and level of distress. Negy and Snyder developed the MSI-R to measure the quality of marital relationships [31]. The MSI-R is a true and false questionnaire consisting of 150-items. It is a self-report that measures the nature and intensity of marital distress [31]. Two validity scales are included in the MSI-R. One of the scales is the GDS, which we used in the present study. The second validity scale contains 10 additional scales to measure specific dimensions of the relationship. All examinees were required to complete the first 129 items. The last 21 items is a scale that measures Conflict over Child Rearing (CCR). Participants without children did not need to answer this dimension of the relationship. | |

| Previous studies have shown internal consistency from a study of 2040 individual participants and 100 participants in couple’s therapy ranged from 0.70 to 0.93 respectively with a mean of 0.82 [32]. Temporal consistency was derived from 200 participants in that were retested after 6 months ranged from 0.74 to 0.88 with a mean of 0.79. For the purpose of this study, the Spanish translation of the MSI-R was also utilized with those participants whose primary language was Spanish. Negy and Snyder conducted a comparison study of the English version to the Spanish translation of the MSI-R [32]. The results of their study showed good internal consistency of the Alpha coefficients had a mean of 0.72 for the Spanish MSI-R. The MSI-R demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.88). | |

| Social Attitudinal Familial Environmental (SAFE) scale: The SAFE Scale was used to assess participants’ acculturation stress. Padilla originally developed the SAFE Scale [33]. The original SAFE scale contains 60 items measuring acculturative stress. The scale measures four areas of acculturative stress: social, attitudinal, familial, and environmental. The SAFE Scale was then abbreviated by Mena, Padilla and Maldonado [34] and contains 24 items. The 24-item SAFE acculturation scale has adequate validity and reliability for use with Latinas/os in the measure of acculturation stress [35]. Twenty-one of the items are Likert scale items and three are open-ended questions. Participants are asked to rate how stressful each item is on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (item is not stressful) to 5 (item is extremely stressful). If an item is not applicable to the participant they assign a 0 [34]. Possible scores range from 0-120. | |

| The 24-item SAFE Scale has a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.89 [34]. In their study of immigrant respondents, Mena found that participants who migrated before age 12 (early immigrants) had significantly lower acculturative stress (F=1.15; df=1, 84; p<0.05) than those who migrated after age 12 [34,35]. The SAFE Scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.73) | |

| Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ): The SSQ was used to assess participants’ social support. The SSQ was developed by Sarason, Levine, Basham, and Sarason [36] consists of 27 items designed to measure perceptions of social support and satisfaction with social support (Tables 1, 2). Each item asks respondents to provide a two-part answer. The first response solicits respondents to list all the people that fit the description of the question. The second part asks respondents to indicate how satisfied they are, in general, with these people on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very unsatisfied) to 6 (very satisfied). In the original study Sarason examined a total of 602 undergraduate students from University of Washington [36]. The alpha coefficient of internal reliability for the English version was 0.97 [36]. The alpha coefficient of internal consistency of the Spanish version was 0.94 [37]. The alpha coefficient for (S) scores was 0.94. The test-retest correlations for the (N), and (S) scores were 0.90 and 0.83 respectively [36,37]. The SSQ demonstrated adequate internal consistency in the current sample (Cronbach’s alpha=0.76). | |

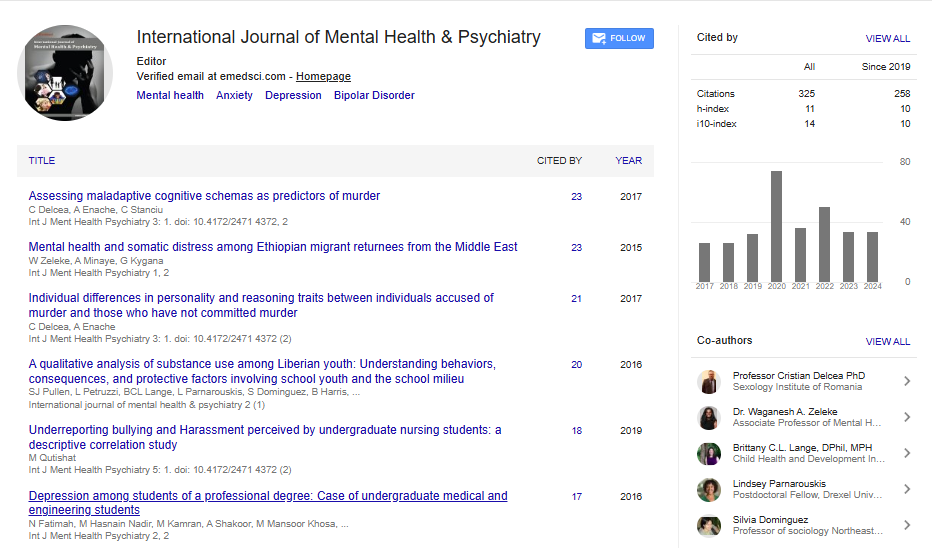

| Table 1: Descriptive Statistics of Demographic Variables. | |

| Table 2: Model Summary of Variables Predicting MSI-R (N=92). | |

Results |

|

| A multiple regression analysis was used to test if attachment style, acculturative stress, and social support significantly predict marital distress. The results of the regression indicated the three predictors explained 47.5% of the variance (R2=0.475, F (4, 87)=19.68, p<0.001). The overall regression model was significant (Table 3). | |

| Table 3: ANOVAa Table for Regression Analysis. | |

| Research Question 1 | |

| The first research question was designed to examine whether the attachment style in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children predict marital distress. Attachment style significantly predicted marital distress (β=0.630, p=0.000). Since the p value is less than 0.05 (Table 4), we can conclude that the variable attachment style predicts the marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children. | |

| Table 4: Regression Coefficientsa for the PAM and MSI-R. | |

| Research Question 2 | |

| The second research question was designed to examine whether acculturative stress predicts marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children. Acculturative stress significantly predicted marital distress (β=0.341, p=0.001). Since the p value is less than 0.05 (Table 5), we can conclude that the variable acculturative stress predicts marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children. | |

| Table 5: Regression Coefficientsa for the SAFE Scale and the MSI-R. | |

| Research question 3 | |

| The third research question was developed in order to examine whether social support predicts marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children. Social Support (SSQN) does not significantly predict marital distress (β=-0.156, p=0.136), and (SSQS) does not significantly predict marital distress (β=-0.131, p=0.21). Since the p value is more than 0.05 (Table 6), we can conclude that the variable social support, does not predict marital distress in adult immigrants separated from their primary caregivers as children. | |

| Table 6: Regression Coefficientsa of the SSQ (SSQN and SSQS) and the MSI-R. | |

Discussion |

|

| The purpose of this study was to examine if variables (attachment, acculturative stress, and social supports) in Mexican and Central American immigrants who were separated from their primary caregivers as children predict marital distress. Research has demonstrated that Mexican immigrants who were separated from primary caregivers when migrating as children may develop acculturative stress and lack of social support upon entering the United States [6,7]. According to attachment theory, separation of primary caregivers may lead to avoidant attachment style correlating to marital distress [9]. Previous studies suggested that as immigrants acculturate, divorce rates rise due to economic, social, and political challenges [38]. Ribeiro found that low social support correlated with high marital distress [7]. Although findings correlated immigration with acculturation stress, which contributes to psychological, relational, and emotional problems [39], there has been a lack of research on the effects of immigration stressors on Mexican and Central American immigrant couples [19]. Therefore, this study was designed to expand the research on how immigrant distress, separation, attachment, and social support predict Mexican and Central American marital relationships. | |

| Findings revealed a significant relationship between attachment, acculturative stress, and marital distress in Central America and Mexican immigrants who were separated from their primary caregivers as children. Further analysis of the findings revealed no significant relationship between social support and marital distress. However, when examined closely, findings confirmed that the model summary was significant because the predictors of attachment, acculturative stress, and social support explained 47.5% of the variance in predicting marital distress. | |

| Attachment style and marital distress | |

| In the current study, the PAM measured participants’ level of attachment. A higher PAM score indicates higher levels of anxiety and avoidant attachment [29], whereas the median score indicated moderate levels of insecure attachment styles. However, although participants did not score extreme levels of insecure or lack of insecure attachment styles, the regression analysis indicated that attachment style significantly predicted marital distress. Furthermore, participants who were separated at a younger age (ages 2 to 5) whose separation lasted more than 5 years showed higher levels of anxious and avoidant attachment. In contrast, if a child was separated at a later age (ages 10 to 15) and his or her separation was under 5 years, the participant showed lower levels of anxious and avoidant attachment. These findings supported prior research that found that longer immigrant separation correlated with higher levels of distress and psychological/psychosocial problems [6]. Also, adults with longer separations from mothers tend to have avoidant attachment styles [40]. These findings supported Bowby’s attachment theory in that the first 5 years of an infant’s life are indispensable in the development of healthy attachment towards primary caregivers and towards others later in life [22]. | |

| The findings of the current study supported other research on couple and family therapy and attachment. Johnson reported that anxious and avoidance attachment styles can be viewed as natural responses to not feeling a secure connection with a partner [41]. This assertion supported other works by previous researchers [23,42] in that it establishes links between early attachment security in relationships with parents and later social/emotional functioning. Participants in the present study that reported higher scores of martial distress also reported higher scores of anxious and avoidant attachment. One of the styles of communicating in many couples is affective communication, which is measured in the MSI-R used in this study. Participants who scored higher avoidance attachment in the PAM also reported having very low affective communication styles. This study found a relationship between the PAM and the MSI-R scores. Affective communication is the amount of affection and understanding of the other partner [43]. Affective communication is seen in couples when partners show enough affection, partners are sympathetic, supportive, sensitive, trusting, and do not withdraw from partners. All of these questions support internal working models [23] that may lead to anxious or avoidant attachment styles predicting marital distress. | |

| Results from this study were similar to studies on the relationship of insecure attachment styles, which predict marital distress being a result of immigration-induced separation [44]. Those studies revealed that moderate levels of anxious and avoidant attachment style due to childhood separation can predict marital distress. The results of this study can inform marriage counselors on how attachment insecurities affect immigrant couples. Also, because marriage is central in Latina/o families [45] having an understanding on how attachment due to immigration separations affects the couples’ well-being and parentchild relationships is imperative. The present study showed that anxious and avoidant attachment styles predict marital distress. | |

| Acculturative stress and marital distress | |

| For immigrants it is difficult to fit into a new country where the language, customs, values, laws, food, holiday celebrations, childrearing practices, philosophy of marriage, and emphasis on individualism are different than in their country of origin. Immigrants’ process of acculturation can be very difficult because of their inability to adapt and cope with stressors. This is especially true of immigrants who arrive in this country later in life. Participants in the current study who arrived in this country after the age of 17 and showed higher levels of acculturative stress. Ribeiro concluded that high levels of acculturative stress through loss of social supports, conflict within the family, and discrimination can impact marital distress [7]. Previous research concluded that high levels of acculturative stress increased poor health, alcohol and drug use, family conflicts, and marital distress [5]. Also, Latina/o immigrants like those in in the current study differ from other immigrants from northern and western Europe. Latina/o immigrants face racial discrimination and prejudice due to their skin color. | |

| This study found that acculturative stress significantly predicts marital distress. Although participants did not report their acculturative stress to be extremely high, the significance of this variable on marital distress can be explained by the importance of the immigrants’ interaction with the microsystem and the macro system. Because immigrants are predisposed to internal and external stressors prior to migration, during migration, and post migration, the accumulation of stress (in some cases trauma) can create a greater strain on marital distress. This may be true even when the participants’ current acculturative stress is not as high. Participants in the study who reported higher levels of acculturative stress may have been experiencing marginalization, oppression, language difficulties, underemployment, poor health, and psychosocial stressors [46]. | |

| Prior research has also discussed the conflict in immigrant couples resulting in the roles of the woman changing from being the homemaker and stay-at-home mother to now working. In some cases, the man may stay home due to his legal status and inability to find work [19]. Moreover, the woman’s role as the breadwinner results in financial independence, mobility, and autonomy. This change of roles can result in marital conflicts between immigrant couples. Hence, the roles that immigrant women have can lead to marital conflicts. In the present study, most of the participants were either working full-time or part-time. This acculturative stress may have been enough to increase participants’ marital distress. This result can be further explained by one of the scales of the MSI-R. The Role Orientation scale may be directly linked to acculturative stress. | |

| Role Orientation in the MSI-R is a scale consisting of 12 items measuring the extent to which the respondent views his or her relationship as traditional versus nontraditional [43]. For example, the Role Orientation measures whether respondents believe both partners should assume equal responsibility for housework and child care, whether women should be given greater opportunity to work outside the home, and whether the woman rejects the notion of male dominance in the home [43]. Negy et al. reported that marital relationships may be more distressful to women because of the multiple demands placed on them (i.e., domestic responsibilities, working, managing career aspirations) [5]. Immigrant women’s adherence to maintaining their cultural role is in conflict with pressure to acculturate [5]. The same can be said for Latino men whose new role is foreign to their cultural values. The change in roles, language, customs, values, heightened awareness of one’s immigrant status, discrimination, oppression, and work status have been found to impact marital distress [5]. | |

| Social support and marital distress | |

| Research showing the correlation between lack of social support and marital distress was limited to a study conducted by Ribeiro who found that lack of social support is associated with psychological problems that directly impact marital relations [7]. However, Riberio conducted research on immigrant men. The lack of research on social support’s impact on male and female immigrants’ marital relationship justifies the investigation of this variable. However, the findings of this study did not confirm the lack of social support predicting marital distress. The results of this study found that participants had a good support system of at least 58 people in their lives. They described being very satisfied, fairly satisfied, or a little satisfied with their social support. Satisfaction with social support was not skewed whether participants responded having two consistent people in their support system or 10 individuals. This means that for immigrants in a new country the individuals identified as that person’s social support are critical. Previous studies have shown that social support serves as a buffer to acculturative stress in immigrant men [7]. However, the current study did not show a statistically significant result for social support or lack of social support buffering marital relationships or predicting marital distress respectively. Nonetheless, as reported in the results chapter, the overall regression model (attachment, acculturative stress, social support, and marital distress) was significant. | |

| Previous research described how familism, or the belief of family over the individual, may serve as a social support for Latina/o families [18] and the loss of those social supports in a new culture can bring on psychological problems [17]. However, these studies failed to directly relate findings to marital distress. The present study also does not support the hypothesis that the lack of social support in immigrants predicts marital distress. Participants responded favorably to having important individuals in their lives that are part of their support system. In addition, participants were satisfied with the social support received from them. However, these findings supported prior research that reported that Latina/o immigrants place a higher emphasis on collectivism over individualism [38]. | |

Limitations of the Study |

|

| Participants were limited to immigrants from Mexico and Central America, currently married, and who were separated as children from their primary caregivers. Generalizability should be made with caution. Because participants were recruited from offices providing immigration services, their characteristics may have influenced the results. Participants who responded saw the flyers while in the offices where they were to receive services to become a legal resident, apply for provisional unlawful presence waivers, or immigrant Visas. Their participation in the study may have been influenced by their fear of deportation, frustration, anxiety, or the perception that by completing the surveys they may somehow change immigration policy. Perhaps in the future if participants are recruited from other settings (e.g. college campuses, malls, work settings), the results may be different. The interaction of history is another limitation. Because of the current political rhetoric on immigration, participants may be experiencing more acculturative stress than they were a year ago or may experience in the future. | |

Recommendations for Future Research |

|

| This study highlights the importance of attachment theory, acculturative stress, social support, and separations from parents as factors for marital distress in immigrant couples. Anxious attachment and avoidant attachment styles tend to be associated with marital distress. While the relationship between social support and marital distress was not significant further research is needed in order to examine this variable. Because this study focused on males’ and females’ social support in a marital relationship, additional research should focus on immigrant couples (married to each other), how their lack of social support may predict marital distress, and how satisfaction with social support may serve as a buffer to marital distress in immigrant couples. In addition, although the relationship between attachment and acculturative stress was significant, future research should focus on having a control group with immigrants who were not separated from their parents as children and an experimental group with immigrants who were. | |

| Also, although both males and females were examined in this study, we did not focus on how males and females differ in their attachment, acculturative stress, or social support. Further research to examine these differences is warranted. Specifically more research is warranted to examine how these differences may predict marital distress in immigrants who were separated from their parents as children. Negy et al. reported that the correlation between social support and marital distress is stronger in males than in females but did not factor in whether they were separated as children [5]. Also, Negy et al. reported that the correlation between acculturative stress and marital distress was higher for women than for men but did not factor in the separation. Finally, another recommendation for future research is to conduct a longitudinal study that examines immigrant couples, separated as children from their primary caregivers and whether the variables attachment, acculturative stress, and social support predict marital distress over time. A longitudinal study will be useful in establishing causal relationships and for making reliable inferences. In addition, sampling errors are reduced, as the study participants remain the same over time [47]. | |

Implications |

|

| When treating Latina/o immigrants with multiple barriers to mental health, language problems, history of immigration trauma, acculturative stress, underemployment, separations from primary caregivers, attachment insecurities, and fear of deportation, it is imperative to assess these immigrant clients differently than Englishspeaking non-immigrant clients. It is important to assess the many unique experiences that immigrant clients face. Bemak, Chung, and Pedersen suggested that clinicians use the Multi-Level Model of Psychotherapy (MLMP), Counseling, Social Justice, and Human Rights for Immigrants when treating immigrants and refugees [48]. Bemak et al. argued that clinicians should assess the culture, premigration experiences, acculturation, post migration, and psychosocial adjustment issues [48]. Furthermore, Chung, Bemak, Ortiz, and Sandoval- Perez recommended that clinicians incorporate five levels in their intervention when working with immigrant clients [49]. The five levels are as follows: (a) Providing mental health education to immigrant clients, (b) individual, group, and family counseling interventions, (c) cultural empowerment, (d) the integration of cultural adaptations and interventions that integrate traditional with Western healing practices, and (e) addressing human rights and social justice issues. | |

| An understanding of immigrants who were separated as children from their parents will allow researchers to better develop effective immigration policies and effective programs, which meet the needs of immigrant families [50]. Understanding the role of attachment (e.g., healthy, insecure), acculturative stress, the role of social supports, and separation due to immigration can assist clinicians to develop effective treatments that are unique to immigrant families. As reported earlier, attachment was statistically significant in predicting marital distress. Thus, the results of this study will inform researchers, clinicians, immigration policy makers, and politicians on the variables that can impact many immigrant couples. | |

Impact for Social Justice |

|

| Current immigration policy deports parents from this country that has no legal authority to be in the United States, irrespective of whether they have a family, citizen spouse, small children (citizen children), are law abiding, or have a job. By understanding the effects of separation due to immigration, immigration policy may be influenced so that children are not separated from their parents as a result of the current immigration policy. Reunification programs may also be established in communities where immigrant populations reside. Funding for reunification and therapeutic programs may also follow. In addition, this study will also help inform marriage counselors regarding acculturative stress and separation factors that can impact immigrant couples. The results of this study can have social justice implications as immigrant families may be kept intact, the perception of immigrants can be humanized and the image of immigrants can be decriminalized. | |

Conclusion |

|

| Despite the limitations of this study, this study may help researchers and clinicians in having a better understanding of immigrant couples who were separated as children from their parents. The significance of this study is that the results show a first documented link between attachment, acculturative stress, and marital distress in immigrant couples that were separated as children. The results of the multiple regression analysis did show that attachment and acculturative stress predict marital distress. However, the social support variable, which was also tested in the study, was not shown to be significant in predicting marital distress. There continues to be a lack in research on immigrant populations. These researchers hope that the present study will provide a better understanding of immigrant couples that were separated as children. We also anticipate that the explanation of the limitations and the recommendations for future research will promote studies aimed at broadening our current knowledge of what impacts immigrant couples and the immigrant population in general. These findings suggest that interventions with immigrant couples should take attachment and acculturative stress into consideration, as these variables may be a factor into their marital distress. In other words, this study found that high scores in attachment and acculturative stress are predictors of marital distress. As a result immigrant couples may benefit from interventions that specifically address their attachment and acculturative stress. | |

References |

|

|

|

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi