Research Article, Jrgm Vol: 13 Issue: 5

A Pilot Study of Major Burn Injury on Human Adipose Derived Stem Cell Migration, Wound Healing, and Bioenergetics

Olivia Warren1, Jenna Dennis1, Paige Deville1, Cameron Fontenot1, Jonathan Schoen1, Jeffrey Carter1, Herbert Phelan1, Robert W Siggins2, Patrick McTernan2, Jeffery Hobden3, Patricia E. Molina2, Alison A Smith1,2

1Department of Surgery, School of Medicine, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, USA

2Department of Physiology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, USA

3Department of Microbiology, Immunology & Parasitology, Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center, USA

*Corresponding Author: Alison A. Smith

Department of Surgery, Louisiana State University, USA

E-mail: alison.annette.smith@gmail.com

Received: 13-Sep-2024, Manuscript No. JRGM-24-147881

Editor assigned: 14-Sep-2024, PreQC No. JRGM-24-147881 (PQ)

Reviewed: 20-Sep-2024, QC No. JRGM-24-147881

Revised: 25- Sep-2024, Manuscript No. JRGM-24-147881 (R)

Published: 30-Sep- 2024, DOI:10.4172/2325-9620.1000325

Citation: Warren O, Dennis J, Deville P, Fontenot C, Schoen J, et al. (2024) A Pilot Study of Major Burn Injury on Human Adipose Derived Stem Cell Migration, Wound Healing, and Bioenergetics. J Regen Med 13:5.

Copyright: © 2024 Smith AA, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) play an important role in conserving tissue homeostasis and have promise in wound healing strategies in particular for burn patients. This in vitro study examined the effects of burn injuries on ADSC migration and wound healing. We hypothesized that burn injury may impact ADSC function and metabolic activity. Adipose tissue was collected from initial debridement surgeries of severely burned patients. Control ADSC samples were collected from patients undergoing elective plastic surgery procedures. A scratch assay was performed by making a scratch in the ADSC monolayer and migration was captured over a 24-hour period. Cell Mito Stress kit tests were performed to measure metabolic potential. ADSCs extracted from burn patients showed an increase in cell migration, although this difference was not significant (p>0.05). ADSCs isolated from burn patients showed a significant increase in cell velocity (p=0.02), Euclidean distance (p=0.03), and accumulated distance (p=0.02) compared to ADSCs isolated from unburned patients. There was no difference in mitochondrial function between burn and unburned ADSCs (p>0.05). ADSCs isolated from burn patients demonstrated a different wound healing profile compared to ADSCs from non-burn tissue. Future studies are needed to further characterize ADSC function after burn injury.

Keywords: Adipose Tissue; Wound Healing; Scratch Assay; Burns

Introduction

Despite advances in medical and surgical care, the yearly global burden of burn-related injuries remains significant [1]. The complex nature of burn wounds results in increased morbidity and mortality from failure of wound healing. Wound healing entails four phases including: hemostasis, inflammatory response, cell proliferation, and tissue remodeling [2,3]. Chronic wounds result from a disruption in the normal inflammatory response and wound healing cannot progress [4]. Factors that can delay wound healing include chronic disease, infection, malnutrition, age, and patient specific contributors [2]. Successful healing of burn wounds is a major factor in long-term prognosis and quality of life for this patient population [5].

Stem cell derived treatment strategies have potential to improve wound healing [6]. Adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) are easily obtainable, inexpensive to isolate, and could treat chronic wounds [7-9]. Within damaged tissue, ADSCs overexpress proteins that trigger their paracrine, proliferative, metabolic, and migratory capabilities [10-14].

The scratch assay model was developed as a simple and inexpensive tool to measure cell migration [15], a critical component of wound healing. This model has not been previously utilized to study the role of ADSCs isolated from burn patients or to correlate their function with cellular metabolic activity. The primary objective of this study was to employ a scratch assay model to study the effects of burn injuries on human ADSC migration and wound healing in vitro. The secondary objective of this study was to evaluate the metabolic function of human ADSCs following burn injury.

Materials and Methods

Tissue Collection

Adipose tissue was collected from initial debridement procedure of severely burned patients with 20% or greater total burned surface area (TBSA). Control samples were collected from patients undergoing elective plastic surgery procedures (liposuction, abdominoplasty, panniculectomy, breast reconstruction). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, and written informed consent to harvest adipose tissue was obtained from all patients or a legally authorized representative. Baseline demographic information was obtained from electronic medical records.

Cell Extraction and Culture

After collection, adipose tissue was finely minced and weighed. For every 1 mg of adipose tissue, 1 mL of a 1:4 dilution of 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation, NY) in Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) pH 7.4 (1x) (Gibco, Life Technologies Corporation, NY) was used. The adipose in trypsin suspension was placed in a shaker for 30-40 minutes at 37˚C followed by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes at room temperature. The fat layer was decanted. The pellet was resuspended in PBS and filtered using a 100 μM cell strainer into a conical tube and centrifuged. The pellet was re-suspended in 5 mL ACK lysing buffer (Quality Biological, Gaithersburg, MD) and mixed with a pipette for 5 minutes. Fifteen milliliters (3x volume of ACK) of PBS was added to the ACK suspension and centrifuged as described above. The pellet was resuspended in DMEM (1x) +GlutaMAX containing 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic (100x). The suspension was seeded in a cell culture flask and incubated in 37ºC at 5% CO2.

ADSC Confirmation

The immunophenotype of ADSCs was determined using flow cytometry. ADSCs were frozen in liquid nitrogen for storage after reaching confluency. Cells were thawed in a 37ºC water bath for 30 seconds until partially thawed. DMEM+ Glutamax Media with 10% FBS and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic was warmed to 37ºC and then added to thaw the remainder of samples without inducing heat-shock to cells. Cells were stained with eFluor 780 (Fixabile Viability Dye eFluor 780, Invitrogen, Cat# 65-0865-14) to quantify live cells. The cells were stained with antibodies against CD90 (BV421 labelled Mouse Anti-Human CD90, clone 5E10, BD Biosciences, Cat# 562556), CD105 (BB700 labelled Mouse Anti-Human CD105, clone 266, BD Biosciences, Cat#566529), and CD73 (PE-Cy7 labelled Mouse Antihuman CD73, clone AD2, BD Biosciences, Cat# 561258) for immunophenotyping. Stained cells were analyzed using the BD FACS Canto and BD FACS LSRII (BD Biosciences, USA). Cell expressions of the antibody-fluorophore combinations were evaluated on flow cytometry plots using FACSDiva V8.0.3 (BD Biosciences, USA) software.

Scratch Assay

Control or burn ADSCs were plated at 50,000 cells per well in a 12-well tissue culture plate (Costar, Corning Inc). Twenty-four hours after plating, the cell culture media was replaced with FBS-free media and the ADSCs were serum starved overnight. A scratch was then made in the cell monolayer using a sterile 10 pipette tip. ADSC migration was captured using an Olympus IX81 microscope over a 24-hour period. Image J software (version 2) was used to quantify the percent wound healing of the scratch and to track the ADSCs for directionality and velocity. Experiments were performed with three control and three burn ADSC lines. All experiments were performed in triplicate and a total of 30 cells were tracked from each sample (10 from each triplicate) using the Image J “Manual Tracking” plugin. Directionality and velocity were then calculated using the “Chemotaxis and Migration Tool” software from Ibidi (version 2.0 – Independent stand-alone software).

Mitochondrial Function Assay

Control or burn ADSCs were seeded at 40,000 cells per well in a 96-well cell culture microplate (Agilent, CA) in triplicates in 37 ºC DMEM+ GlutaMAX media with 10% FBS and 1% Antibiotic-Antimycotic. The cells were left to rest at room temperature for 1 hour prior to overnight incubation in 37ºC at 5% CO2 to prevent variability in the humidification timing of the outer wells compared to inner wells of the plate. A sensor cartridge (Agilent, CA) was hydrated with pH 7.4 XF Calibrant (Agilent, CA) and incubated in 37ºC non-CO2 overnight. Twenty-four hours later, cells were observed for confluency. The culture media was replaced with Assay Media (Agilent, CA) and cells were incubated in 37ºC non-CO2 for 1 hour. The cartridge was re-hydrated in pH7.4 XF Calibrant and incubated in 37ºC non-CO2 for 1 hour prior to loading Mito Stress Test kit injections. Cartridge injection ports were loaded with 20uL of 1.5uM Oligomycin (Agilent, CA), 22uL of 1.0uM Carbonyl cyanide-4 phenylhydrazone (FCCP) (Agilent, CA), and 25uL of 0.5uM Rotenone/Antimycin-A (Agilent, CA) supplemented with 0.05uL 20mM Hoechst 33342 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Germany) for fluorescence imaging. Brightfield and Fluorescence images were captured with a BioTek Cytation 1 imaging reader (Agilent, CA) and analyzed with Cell Imaging software v1.2.0.12 (Agilent, CA). A Seahorse XFPro machine (Agilent, CA) was used to analyze the cells responses to the Mito Stress Test. Seahorse Wave Pro v10.1.0 (Agilent, CA) software was used to analyze mitochondrial functions of the ADSCs.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Statistical analyses were performed using 2-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparison test to compare changes in time, percent wound open, and tissue type. Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences in cell tracking measurements. Fisher’s Exact and Kruskal-Wallis tests were used to statistically analyze differences in group demographic characteristics. GraphPad Prism 9.3.1 software (GraphPad, La Jolla, California) was used in all analyses and p values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Patient Demographics

All three control subjects were female. Of the three burn subjects enrolled in the study, 100% were male. The mean age and body mass index (BMI), respectively, were 40.0 ± 4.6 years and 33.5 ± 0.3 kg/m2 for the control group compared to 52.7 ± 14.6 years and 26.1 ± 11.5 kg/m2 for the burn group. The mean TBSA for the burn group subjects was 37.7 ± 17.5%. The demographic characteristic, sex, was significantly different between groups (p=0.01) (Table 1).

| Control (n=3) | Burn (n=3) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male, n (%) | 0 (0) | 3 (100) | 0.01* |

| Age, avg (SD) | 40.0 (4.6) | 52.7 (14.6) | 0.4 |

| BMI, avg (SD) | 33.5 (0.3) | 26.1 (11.5) | 0.6 |

| White, n (%) | 1 (33) | 1 (33) | 1.0 |

| AA, n (%) | 1 (33) | 2 (66) | 1.0 |

| Asian, n (%) | 1 (33) | 0 | 1.0 |

Table 1: Patient demographics for the control and burn cell lines

Flow Cytometry

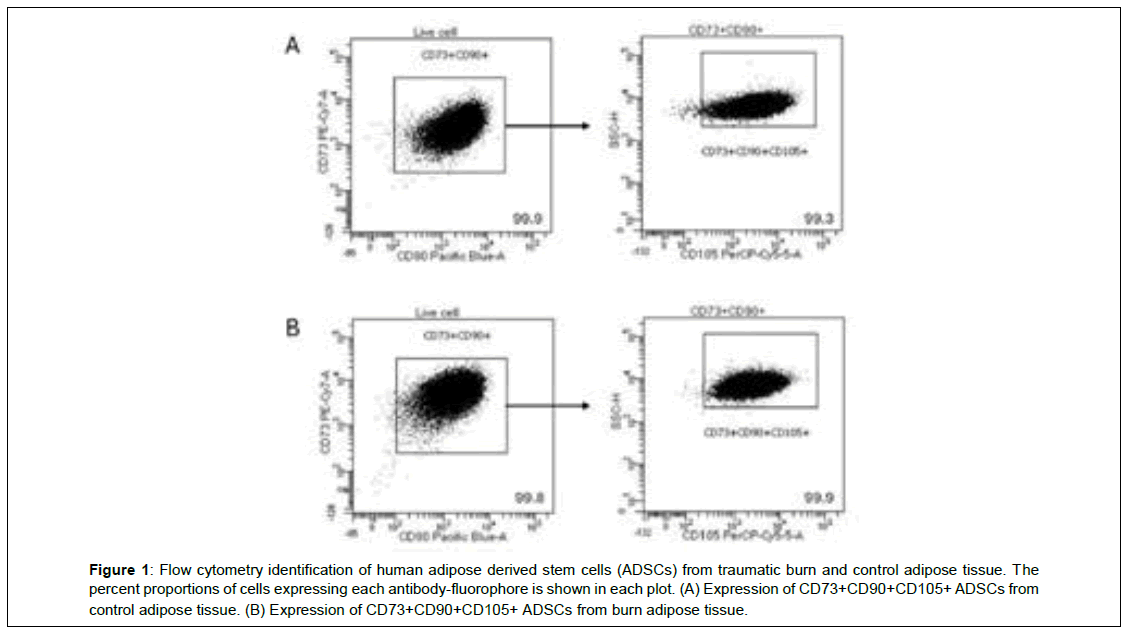

A-B shows the confirmation of cell surface markers CD73, CD90, and CD105 in both control and burn ADSCs in a representative flow cytometry data plot (Figure 1). Figure 1A shows that for live cells, 99.9% expressed CD73 and CD90. Out of all cells that expressed CD73 and CD90, 99.3% also expressed CD105. Figure 1B shows that for live cells, 99.8% expressed CD73 and CD90. Out of all cells that expressed CD73 and CD90, 99.9% also expressed CD105.

Figure 1: Flow cytometry identification of human adipose derived stem cells (ADSCs) from traumatic burn and control adipose tissue. The percent proportions of cells expressing each antibody-fluorophore is shown in each plot. (A) Expression of CD73+CD90+CD105+ ADSCs from control adipose tissue. (B) Expression of CD73+CD90+CD105+ ADSCs from burn adipose tissue.

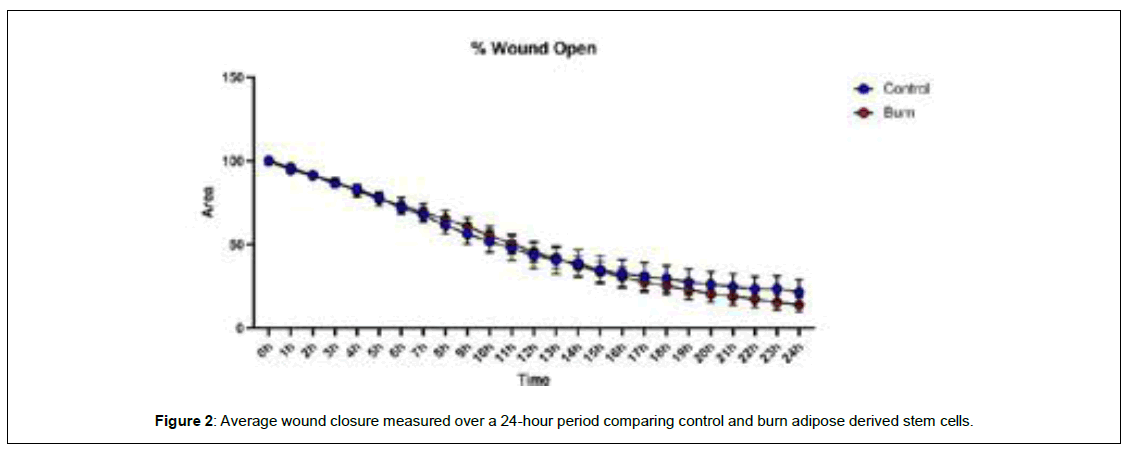

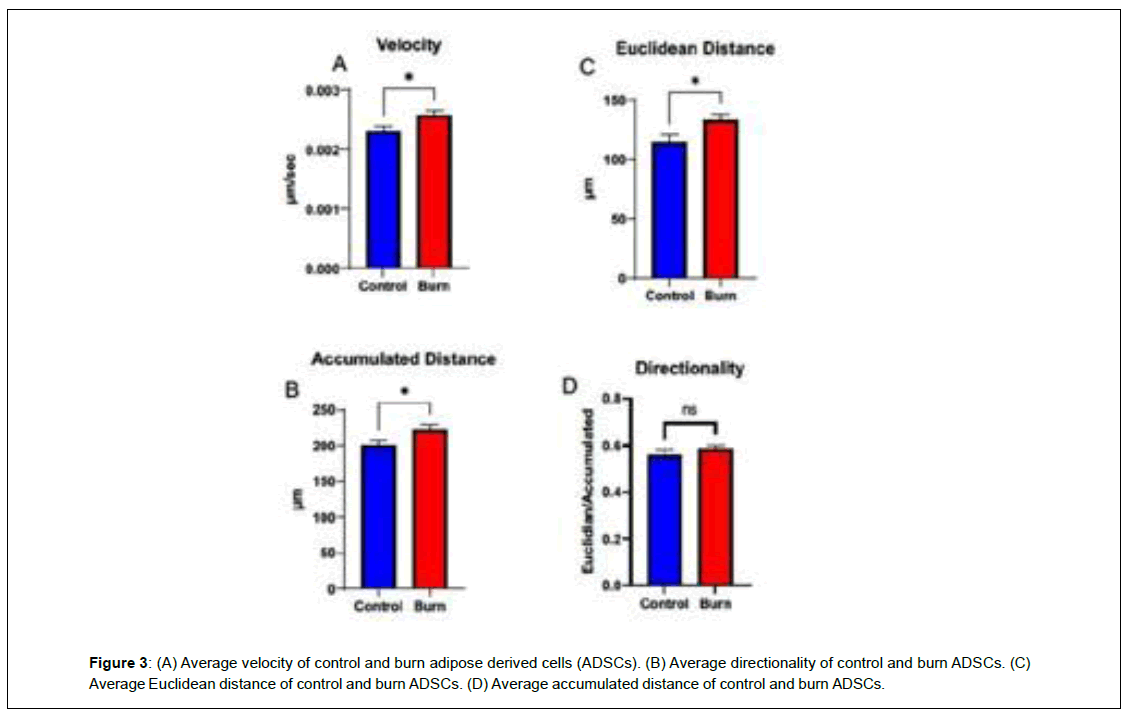

Wound healing

When comparing wound closure, burn ADSCs had a lower percentage of the scratch left open following the 24-hour period, but the difference was not significant (p>0.05) (Figure 2). To measure velocity, directionality, and distance, individual cells were tracked and analyzed. Burn ADSCs showed a significant increase in velocity (control: 0.002 ± 0.0001, burn: 0.003 ± 0.0001, p=0.02), Euclidean distance, distance from initial to final point, (control: 115.1 ± 8.19, burn: 132.9 ± 8.19, p=0.03), accumulated distance, total distance traveled, (control: 200.0 ± 9.95, burn: 223.3 ± 9.95, p=0.02), but not directionality (control:0.56 ± 0.03, burn:0.58 ± 0.03, p=0.32) (Figure 3).

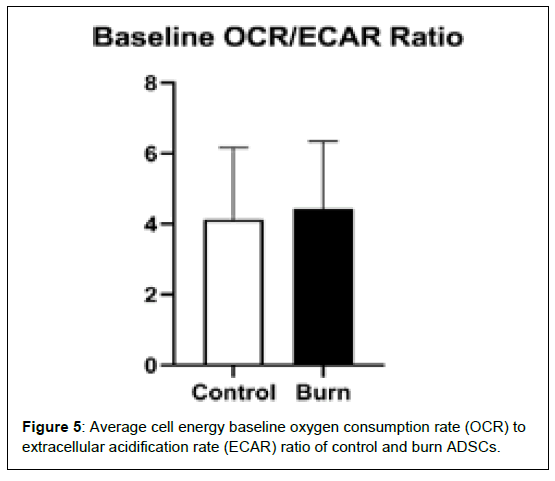

Metabolic Potential

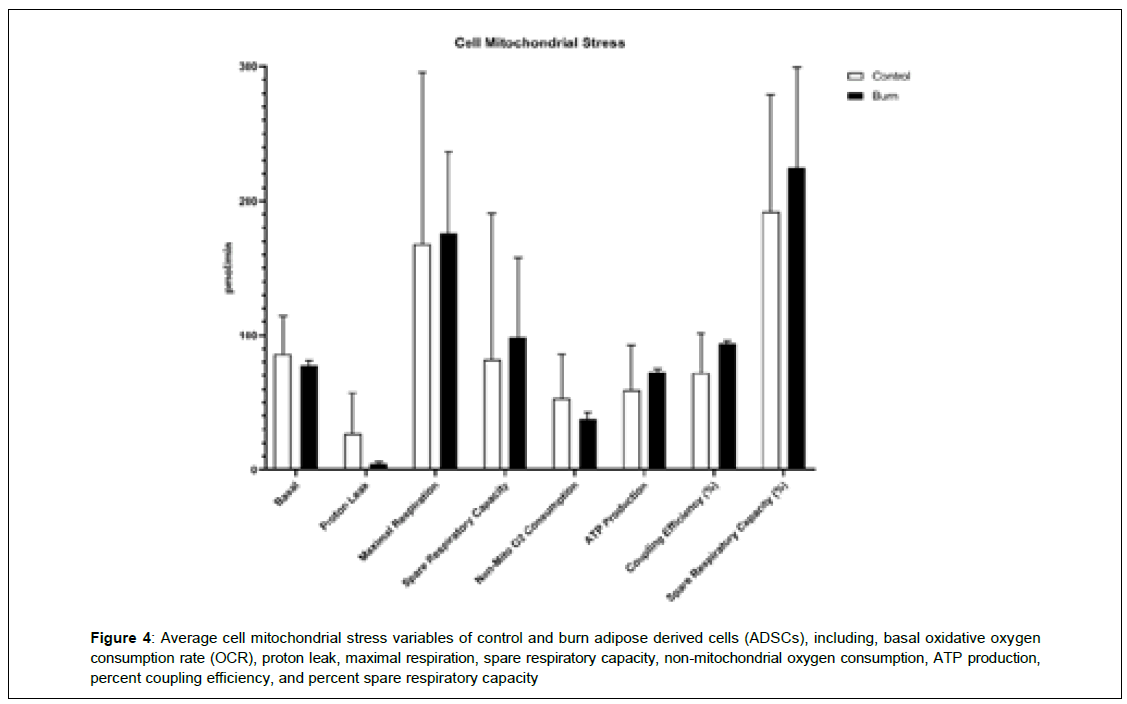

It shows the differences in mitochondrial stress oxygen consumption rate (OCR) levels of several mitochondrial respiration variables, including, basal OCR, proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption, ATP production, coupling efficiency, and spare respiratory capacity (Figure 4). Differences in cell energy phenotypes of OCR levels on control and burn ADSCs, including, baseline OCR, stressed OCR, and metabolic potential based on OCR were measured and not found to be statistically different. There were no differences in the cell energy phenotypes of extracellular acidification rate (ECAR) levels in control and burn ADSCs, including baseline ECAR, stressed ECAR, and metabolic potential based on ECAR. It shows the differences in the baseline OCR/ECAR ratio of control and burn ADSCs. These variables were not significantly different between the control and burn ADSCs (p>0.05) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Average cell mitochondrial stress variables of control and burn adipose derived cells (ADSCs), including, basal oxidative oxygen consumption rate (OCR), proton leak, maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, non-mitochondrial oxygen consumption, ATP production, percent coupling efficiency, and percent spare respiratory capacity

Discussion

The optimal management of burn wounds involves excision and grafting to promote wound healing [16-20]. In this study, we investigated the impact of burn injuries on wound healing and ADSC migration in vitro. Burn ADSCs showed a decrease in the percentage of wound left open after 24 hours compared to the control cells. Burn ADSCs traveled at an average velocity that was significantly higher than the controls. There was a significant increase in both Euclidean and accumulated distance in the burn ADSCs compared to the control. These findings may suggest that ADSCs extracted from burn adipose tissue may have a potential to be used as autologous therapeutic agents.

Adipose tissue is a potential source of cell-directed therapeutics for burn patients. A previous study by Franck and colleagues found that full thickness burn wounds in a rat model had improved healing when treated topically with ADSCs [21]. In contrast, a study by Burmeister and colleagues found that ADSCs harvested from burn tissue become increasingly oxidative leading to free radical production and become less glycolytic with subsequent cell passage numbers [14]. However, the results from our study suggest that ADSCs isolated from burn tissue have the potential to be used in wound healing compared to ADSCs derived from non-burn tissue. Further studies are needed to determine the optimum culture conditions to grow ADSCs for therapeutic interventions.

This study has several limitations which merit further discussion. The small sample size likely limits the widespread applicability of these results. Secondly, there are likely multiple factors present in an actual in vivo burn wound that affect the physiology and subsequent behavior of ADSCs that are not replicated in our in vitro model system. Despite these limitations, this pilot study provides important insight into the in vitro migratory behaviors of ADSCs following burn injuries which can assist in the advancement of stem cells treatments for chronic wounds such as burns.

Conclusion

In conclusion, ADSCs extracted from burn patients demonstrated a unique wound healing profile compared to ADSCs from non-burn tissue. These differences can play an important role in how wounds healing following burn injury and the utilization of autologous adipose tissue from burn patients. Future studies are needed to determine how ADSCs can be harnessed to improve wound healing following major burn injury.

Conflicts of Interest

AAS is a paid consultant for Aroa Biologics and on the advisory board for Prytime Medical. HAP serves as a consultant for Avita and SpectralMD. JEC is a stockholder for SpectralMD and serves as a consultant for Avita, Polynovo Ltd., and Spectral MD in lieu of compensation all proceeds are donated to burn charities. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author contributions

OW: Study design, specimen collection and processing, data analysis, writing of manuscript

JD: Study design, specimen collection and processing, data analysis, writing of manuscript

PD: Study design, Specimen collection and processing

CF: Study design, Specimen collection and processing

JS: Study design, data analysis

JC: Study design, data analysis

HP: Study design, data analysis

RWS: Study design, data analysis

JH: Study design, data analysis, revisions of manuscript

PM: Study design, data analysis, revisions of manuscript

AAS: Study design, data analysis, writing of manuscript

References

- Jeschke MG, van Baar ME, Choudhry MA, Chung KK, Gibran NS, et al. (2020). Burn injury. Nat Rev Dis Primers;6(1):11.

- Zhao R, Liang H, Clarke E, Jackson C, Xue M (2016) Inflammation in chronic wounds. Int J Mol Sci;17(12):2085.

- Hassan WU, Greiser U, Wang W (2014) Role of adipose‐derived stem cells in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen;22(3):313-25.

- Villagrasa A, Posada-González M, García-Arranz M, Zapata AG, Vorwald P, et al. (2022). Implication of stem cells from adipose tissue in wound healing in obese and cancer patients. Cir Cir;90(4):487-96.

- Chang YW, Wu YC, Huang SH, Wang HM, Kuo YR, et al. (2018) Autologous and not allogeneic adipose-derived stem cells improve acute burn wound healing. PLoS One;13(5):e0197744.

- Karimi H, Soudmand A, Orouji Z, Taghiabadi E, Mousavi SJ (2014) Burn wound healing with injection of adipose-derived stem cells: a mouse model study. Ann Burns Fire Disasters;27(1):44.

- Natesan S, Wrice NL, Baer DG, Christy RJ (2011) Debrided skin as a source of autologous stem cells for wound repair. Stem Cells;29(8):1219-30.

- Bunnell BA, Flaat M, Gagliardi C, Patel B, Ripoll C (2008) Adipose-derived stem cells: isolation, expansion and differentiation. Methods;45(2):115-20.

- Zuk PA, Zhu MI, Mizuno H, Huang J, Futrell JW et al. (2001) Multilineage cells from human adipose tissue: implications for cell-based therapies. Tissue Eng;7(2):211-28.

- Mazini L, Rochette L, Admou B, Amal S, Malka G (2020). Hopes and limits of adipose-derived stem cells (ADSCs) and mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) in wound healing. Int J Mol Sci;21(4):1306.

- Gnecchi M, Zhang Z, Ni A, Dzau VJ (2008) Paracrine mechanisms in adult stem cell signaling and therapy. Circ Res;103(11):1204-19.

- Baraniak PR, McDevitt TC (2010) Stem cell paracrine actions and tissue regeneration. Regen Med;5(1):121-43.

- Skalnikova HK (2013). Proteomic techniques for characterisation of mesenchymal stem cell secretome. Biochim;95(12):2196-211.

- Burmeister DM, Chu GC, Chao T, Heard TC, Gómez BI, et al. (2021) ASCs derived from burn patients are more prone to increased oxidative metabolism and reactive oxygen species upon passaging. Stem cell res ther;12(1):270.

- Martinotti S, Ranzato E (2020) Scratch wound healing assay. Epidermal cells: methods and protocols;225-9.

- Rowan MP, Cancio LC, Elster EA, Burmeister DM, Rose LF, et al. (2015) Burn wound healing and treatment: review and advancements. Crit care;19:1-2.

- Desai MH, Herndon DN, Broemeling LY, Barrow RE, Nichols Jr RJ, et al. (1990) Early burn wound excision significantly reduces blood loss. Ann Surg;211(6):753.

- Herndon DN, Barrow RE, Rutan RL, Rutan TC, Desai MH, et al. (1989) A comparison of conservative versus early excision. Therapies in severely burned patients. Ann Surg;209(5):547.

- Saaiq M, Zaib S, Ahmad SH (2012) Early excision and grafting versus delayed excision and grafting of deep thermal burns up to 40% total body surface area: a comparison of outcome. Ann Burns Fire Disasters;25(3):143.

- Stone II R, Natesan S, Kowalczewski CJ, Mangum LH, Clay NE, et al. (2018) Advancements in regenerative strategies through the continuum of burn care. Front Pharmacol;9:672.

- Franck CL, Senegaglia AC, Leite LM, de Moura SA, Francisco NF, et al. (2019) Influence of adipose tissue‐derived stem cells on the burn wound healing process. Stem cells Int;2019(1):2340725.

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Indexed at, Google Scholar, Cross Ref

Spanish

Spanish  Chinese

Chinese  Russian

Russian  German

German  French

French  Japanese

Japanese  Portuguese

Portuguese  Hindi

Hindi